In the wake of George Floyd's death, The Guardian assesses its historical role in slavery

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

On Oct. 14, George Floyd would have turned 50 years old. President Joe Biden issued a statement that said, in part: “Today, we join his family to honor his life and legacy. And we remember the tragedy and injustice of his death that sparked one of the largest civil rights movements in our nation’s history and inspired the world. George Floyd’s murder exposed for many what Black and Brown communities have long known and experienced — that our nation has never fully lived up to its highest ideal of fair and impartial justice for all under the law.”

George Floyd’s murder reportedly sparked “the largest racial justice protests in the United States since the Civil Rights Movement” (Silverstein, 2021, CBS News). In fact, the impact of his murder was visible around the world as people gathered in anger and frustration towards an unjust system that seemingly condones the murder of unarmed Black men.

In Germany, an English soccer player wore a shirt underneath his jersey that said, “Justice for George Floyd.” In New Zealand, protestors of multiple ethnic backgrounds joined together, “creating a movement for racial progress unlike anything the country had seen for years” (Silverstein, 2021, CBS News). In France, protestors demanded acts of justice, not just conversations. One protestor stated, “We’ll protest in the street every week if necessary” (Silverstein, 2021, CBS). In Columbia, Floyd’s death fueled their #BlackLivesMatter protests and inspired citizens to begin filming confrontations with police (CBS Twitter, 2021). The largest protests outside of the U.S. took place in the United Kingdom, where crowds of hundreds gathered outside the U.S. embassies in London and Berlin, protesting the death of Floyd and joining in solidarity with protestors in the U.S. In London, specifically, protestors took a knee for nine minutes in Trafalgar Square before marching to the U.S. Embassy.

Floyd’s death galvanized people around the world around a common cause and sparked a global reckoning with racism.

The board members of one Britain organization, Scott Trust Ltd., which owns The Guardian daily newspaper, decided to move beyond rhetoric and was inspired instead to dig deeply, explore the core reason for the anger and frustration of Black people. In 2020, the Scott Trust commissioned academic researchers to determine if the original backers had ties to the transatlantic slave trade. What they found astonished and embarrassed them.

Special Series: The Guardian's links to slavery

What The Guardian learned about its past and how it connects the Coastal Georgia and the Lowcountry

During the early 1800s, many British business entities invested heavily in industries throughout the colonies and former colonies, such as the United States, that were dependent upon slave labor to fuel the economy and thus their own financial well-being. The Manchester Guardian newspaper (renamed The Guardian in 1959) was founded by cotton merchant John Edward Taylor in 1821 with financial backing from 11 other men (Wolfe-Robinson, 2023) known as the Little Circle, a group of reformist businessmen who established the daily in the aftermath of the 1819 Peterloo massacre.

The Scott Trust Limited issued an apology to the descendants of the enslaved persons identified in their academic research. Additionally, they announced a proposal for a restorative justice program that would extend for at least 10 years.

The academic research revealed that the enslaved Blacks who provided the free labor that fueled the prosperity enjoyed by the founders of the Manchester Guardian were the ancestors of the Gullah Geechee people who toiled cultivating rice, indigo and cotton along the sea islands between Florida and North Carolina and throughout the Lowcountry. When Gen. William T. Sherman presented Savannah as a Christmas gift to President Lincoln in 1864, he specifically noted that Savannah contained “about 25,000 bales of cotton.” That cotton had direct linkage to the Manchester Guardian, so much so, that the Guardian produced a special issue that tells this story, "The Cotton Capital: How Slavery Shaped the Guardian, Britain and the World," which you can read at theguardian.com/news/series/cotton-capital.

The Scott Trust has since initiated steps to address the harm done to Black people that began with slavery. After the research was done and the report written, the Scott Trust board asked this question: “If we can inherit wealth and benefit over centuries from compound interest, do we not also equally inherit responsibility?"

They rightfully noted that ugly parts of history do not stay neatly in the past. They noted that chattel slavery left two fundamental legacies:

inequality between the people who benefited from the wealth generated from slavery and the communities who have suffered and “continue to suffer because of the crimes against their ancestors and the economic system built on the back of their enslavement,” and

the existence of a racial hierarchy that has lasted for centuries.

These two fundamental legacies are the backdrop for the Scott Trust Legacies of Enslavement Project.

An initial team came to the Lowcountry and met with people in the Gullah Geechee communities within the Gullah Geechee Cultural Heritage Corridor. Washington Post writer DeNeen Brown travelled along the Corridor to gather stories of the direct descendants of those enslaved Africans who picked the cotton that contributed to the wealth of the both the city of Manchester and the founders of The Guardian. Among those she interviewed included Donelia Chives, a trustee of the Penn Center; Queen Quet, Chieftess of the Gullah Geechee Nation; Patt Gunn, a noted Gullah Geechee elder and activist; Victoria Smalls, executive director of the Gullah Geechee Cultural Heritage Corridor; Emory Shaw Campbell, affectionally known as the “Godfather of Gullah; and Maurice Bailey of Sapelo Island.

A second team of people recently visited Savannah, Charleston and Jacksonville to begin exploring ways the Scott Trust could become involved in restorative justice and reparations. I was invited to a meeting hosted by Patt Gunn at the Susie King Taylor Center where I was introduced to Joseph Harker, the Guardian's senior editor of diversity and development; Ebony Riddell Bamber, program director of the Scott Trust’s Legacies of Enslavement Project; and Cassandra Gooptar, an interdisciplinary researcher for the Scott Trust’s Legacies of Enslavement Project. That meeting was electric as we discussed tangible ways in which the Legacies of Enslavement Project could engage in reparations across the Gullah Geechee Corridor. This effort will not be a one-and-done endeavor. It will be far-reaching and long-lasting. Rather, it is about developing a relationship with the descendants of enslaved Africans — listening to them and together deciding what atonement looks like.

The Legacies project is slated to take 10 years.

The Guardian's self-reflection is a model for reparations

I asked Harker and Bamber what they want people to know about their efforts. They first emphasized that they are still learning and there is much work to be done before money is distributed to fund reparation efforts. They stressed that they want people in the Lowcountry to know that The Guardian has a desire to listen and hear them and understand the issues and challenges facing them. Additionally, it is important that descendants of enslaved Africans know that The Guardian is a voice for them.

The Scott Trust has committed $10 million to the Legacies of Enslavement Project. That’s not salaries, administration fees, etc. ― that’s $10 million toward the betterment of Gullah Geechee communities across the Lowcountry and in communities in Jamaica with descendants of enslaved people. According to Harker and Bamber, an ideal result is that the Gullah Geechee community sees The Guardian as a partner in their restoration and that they feel empowered. The Guardian wants to be a model of what can be done to repair damage to descendants of enslaved communities. Additionally, they want to encourage other institutions to go on this journey, as painful and as uncomfortable as it may be.

Earlier this year I traveled to Minneapolis with my sisters and saw firsthand the sacred memorial that marks the very ground where Floyd died. I marveled at the efforts to make something beautiful out of that ugly moment with the breathtaking paintings and murals on surrounding buildings. With emboldened hesitancy, I walked onto the George Floyd Square past the entry sign which read, “You are now entering the free state of George Floyd.” With tears in my eyes, I read the words on a sign penned by Miss Mari: “For every Black man and woman who called out to their mothers because Heaven was approaching faster than the paramedics. I now see the privilege – not in my circumstances, but in the breath I still breathe – because the driver’s license I carry reads more like an obituary when found in the hands of the police.”

I wept and knelt at the “Say Their Names” Memorial Cemetery that memorializes Black lives lost to police brutality. The cemetery encompasses more than 100 headstones made of cardboard, plastic and paper ― each marked with the name of a Black person killed by police. It is one block from where Floyd took his last breath.

The weight of the knee that killed Floyd was felt by millions of people around the world. Many protested. Many rioted. Many got angry. Many cried. The Guardian got busy with the work of trying to right the wrong that is the fundamental source of the anger, frustration and tears – the enslavement of millions of Blacks that fueled the economy in both the U.S. and Britain.

The U.S. can learn from Britain. Companies across the U.S can learn from The Guardian. Together, the oppressed and the oppressor can work to make amends and create a different reality for generations to come. What The Guardian is doing is courageous. Do we, in the U.S. have that same level of courage?

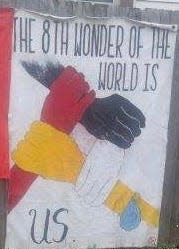

I end this column with words from a painting on the fence next to the “Say Their Names” Memorial Cemetery: “The 8th Wonder of the World is US.” The wonders of the world represent the world’s most spectacular natural features and human-built structures. This sign reminds us, as humans, that we too are world wonders; we are spectacular, phenomenal and powerful. That means we have the capacity to change the world we live in. With regards to race relations in the U.S., the question remains, “Will we?”

Maxine L. Bryant, Ph.D., is a contributing lifestyles columnist. She is an assistant professor, Department of Criminal Justice & Criminology; director, Center for Africana Studies, and director, Gullah Geechee Cultural Heritage Center at Georgia Southern University, Armstrong Campus.

Contact her at 912-344-3602 or email dr.maxinebryant@gmail.com. See more columns by her at SavannahNow.com/lifestyle/.

This article originally appeared on Savannah Morning News: The Guardian visits Gullah Geechee community for Legacies of Enslavement