Want to see 2 million years of life? Visit the Lubbock Lake Landmark archaeological dig

LUBBOCK — One tourist site in this West Texas city is like no other.

The Lubbock Lake Landmark, which celebrated its 50th anniversary of continuous research and public programs in late July, is an archaeological dig that has unearthed more than 12,000 years of human presence in this area, along with more than 2 million years of prehuman activity at the springs known to the Spanish as Punta de Agua, or "point of water."

These reed-ringed springs, located just northwest of downtown Lubbock on the Yellow House Draw, feed into the Double Mountain Fork of the Brazos River. In earlier times, they watered now-extinct animals such as mammoths, camels and giant armadillos as well as the ancestors of the modern bison.

Humans arrived sometime before the age of the Clovis people, so named for a site in New Mexico where their characteristic artifacts were first identified, usually dated from 10,000 to 12,000 years ago. Increasingly, the evidence suggests that human activity in this region goes further, perhaps to 20,000 years ago, as identified at the Gault Site in Central Texas.

More: Say yes to everything: From upscale to diners, here's where to eat and drink in Lubbock

These springs later attracted Native American descendants of the Paleo-Indians, as well as Spanish explorers and traders, and the earliest Anglo-American ranchers and settlers in Llano Estacado.

Yet the importance of the site was not discovered until 1936 when the city of Lubbock tried to dredge the marshy area, then abandoned the work.

Curious how many such stories start this way.

"Two teenagers exploring the piles of sediment left by the dredging found some bones and stone points," reports the Lubbock Avalanche-Journal. "They took their finds to Curry Holden, who was director of what was then called the West Texas Museum and a professor of history at Texas Technological College. He recognized the material as ancient bison bones and a Folsom point."

Periodic digs in the area continued into the late 1960s, but the Landmark lacked a systematic study and a public-facing identity.

"But that changed when Craig Black was recruited from the University of Kansas to become director of the Museum of Texas Tech University in 1972," the Avalanche-Journal article continues. "He brought along a few of his graduate students, including Eileen Johnson. She remembers he told her, 'here was a local site that a lot of community people thought would be important' and 'something needed to be done with it.'

"Little did Johnson know that 50 years later, she would still be doing something with the site and sister excavations at several regional sites."

That's right: As almost everyone at the Landmark told me during my visit in July, the site has had just one director, Johnson, for the past 50 years.

"It was a time to give back and thank the greater community for 50 years years of support for our research and public programming," Johnson later told me. "They've always gone hand in hand. I did the first public program in 1973. I am a firm believer in having the community as part of every aspect of what we do at the Landmark."

This time of year, her scientific teams, based at the Landmark, fan out over sibling sites in the region every summer.

“I’m highly vested in this region," Johnson told Authentic Texas magazine. "To me the heritage of this region deserves people that will be highly invested in it and actually be here to contribute to various aspects.

"I’ve spent so much time here and yet I’ve only scratched the surface.”

Visiting the Landmark

Reaching the site by car at 2401 Landmark Dr. outside Loop 289 is no easy task for the first-time visitor. Flanked in some directions by industrial sites and in other ways by freeways, it lies above Hodges Park on the Yellow House Draw. (Turns out there is an dedicated exit off 289, but we had approached the Landmark from surface roads.)

At least during the summer, it's helpful to avoid looking for a lake in the regular sense. This is really a 12-acre wetland, full of sediment at the base of grassy hills. Viewed on a topographical map, the crooked wetlands look like a leaping fish.

Arriving at the Landmark, one first sees outdoor statuary that indicates the awe-inspiring sizes of some of the early animals. Down a gentle slope, the visitor enters an up-to-date museum that clearly tells the story of the prehistory and history of the site. Furnished with handout maps, one then circles the active digs behind the museum, or takes interpretive trails around the rest of the 300 acres.

More: Texas road trip: 10 things you absolutely must do in the historic city of Lubbock

Admittance is free. While we were there, at least four people, including guest artist La Gina Fairbetter, answered our questions. Fairbetter, who painted the enormous murals at Lubbock's American Windmill Museum, explained how a replica of an extinct American lion skeleton — one of the species discovered by Johnson's teams — would be placed in a display landscape that looks a lot like the reedy springs we later circled.

The museum's exhibits follow a logical pattern that includes a history of digs since the 1930s, looks at geology (the bedrock below us is Blanco Formation), biology and hydrology, the sequence of carbon dating artifacts, ancient animals, Paleo-Indian and Native American cultures, the arrival of the Spanish and the Anglo-Americans, and the remains of Lubbock's first retail outlet, a mercantile store established by George W. Singer.

With his family, the Ohio native opened his store on what was then called "Long Lake," miles away from any other inhabitants, in 1881. Additional exhibits explain the shrinking ranges of the bison, the rise of ranching and cattle brands, and the making of rough pioneer dugout shelters.

One of the things you begin to realize at the museum is that few archaeological sites in North America have produced so much evidence of continuous activity.

The Landmark turns 50

The regional archaeological work based at the Lubbock Lake Landmark covers the Quaternary Period, in other words, about 2.6 million years ago until the present.

“I don’t think of myself as an archeologist at all," Johnson told Authentic Texas magazine. "I’m a quaternary research scientist. Another term would be a paleo-biologist. I’m interested in the entire quaternary — the last 2.6 million years. That’s a lot of time before people.”

Tours began in 1974 with large tents employed for public programs. The site is now a designated National Historic Landmark, a State Archeological Landmark, and is on the National Register of Historic Places.

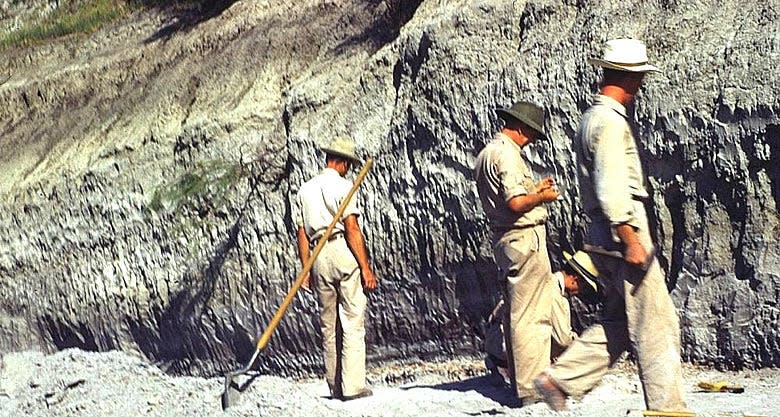

Activities during Celebration Week in late July included tours that stopped at an active dig, Native American storytelling and pottery demonstrations, talks on cattle grazing and branding on the South Plains, and stone toolmaking demos.

"We've been here so long, it's become generational," Johnson says. "Kids who came here in the '70s and '80s are bringing their children, who in turn are bringing their children. We take kids as young as 13 into labs, and as young a 15 into the field. Some of them have gone on in their education all the way to Ph.D.

"Everybody should be involved if they want to be," she continues on the subject of her views on science. "This is a very different from the approach from the one taken at the time in 1973, and even from most research projects today. In order to do what we are doing, we need an educated public to support us."

Even after 50 years as director of this groundbreaking project, Johnson still tends to deflect praise to others.

“The Landmark would not be here today without Curry Holden," Johnson told Authentic Texas about the historian, archaeologist and former director of what is now the Museum of Texas Tech University. He died in 1993. "He’s probably one of the greatest visionaries I ever knew. He was very committed to community involvement, preservation, education, interpretation and research.

"Those principles and concepts have guided me. I fully believe in all of them, then and now.”

Lubbock Lake Landmark

Where: 2401 Landmark Dr., Lubbock

When: 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. Tuesdays through Saturdays, 1 p.m. to 5 p.m. Sundays

Tickets: Free

Info: lubbocklake.ttu.edu, (806) 742-1116

This article originally appeared on Austin American-Statesman: Lubbock Lake Landmark dig records more than 2.6 million years of life