'War Is Betrayal.' Coming to Terms With America's Disastrous Departure from Afghanistan

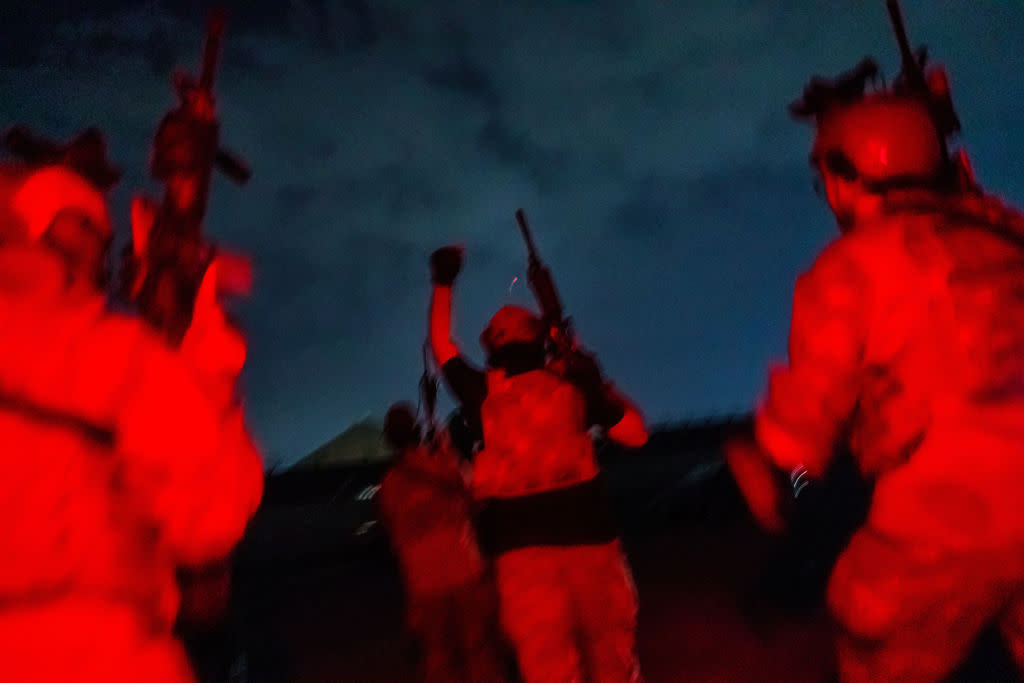

Taliban fighters from the Fateh Zwak unit storm into the Kabul International Airport, wielding American supplied weapons, equipment and uniforms after the United States Military have completed their withdrawal, in Kabul, Afghanistan, Tuesday, Aug. 31, 2021. Credit - MARCUS YAM-LOS ANGELES TIMES/Getty

As the Taliban took Kabul, the phones of veterans across America began lighting up with messages from Afghans they’d worked with: “Please help.” “My family is in danger.” “If I don’t get out I’m going to die.” The Taliban had waged a murder and intimidation campaign for years, targeting those who’d worked with the Americans, who’d championed women’s education, who’d worked in government. Now, with the American withdrawal and the collapse of the Afghan government, those who’d believed in American promises were under threat like never before.

One of those veterans receiving messages was my friend Elliot Ackerman. A distinguished novelist (author of the National Book Award finalist Dark at the Crossing and co-author, with Admiral James Stavridis, of the New York Times bestseller 2034) and essayist (for the New York Times, Atlantic, and TIME), Elliot also had spent years as one of America’s most elite warfighters. A Silver Star and Purple Heart recipient, he’d served as a Marine infantry officer at the Battle of Fallujah, then in Marine Special Operations Command, and finally in the CIA’s Ground Branch, where he’d worked closely with Afghans. That meant not only that the Taliban’s victory threatened those he’d fought with, but that he was uniquely situated to reach out to contacts to help people on those desperate flights out of Kabul.

His new recent book, The Fifth Act, is an astonishing account of that time, and of the relationships and crises forged in combat in Afghanistan. I spoke with him over Zoom about the end of the war that has defined so much of his life, and the desperate scramble that began last August.

Klay: I thought I would begin with the very opening, which is beautifully written. “The war has always been there, even though I don’t go to it anymore. It is older than my children who sleep in the room next door. I learned to love it before I learned to love my wife, who fits her body beside mine in the bed. The war is ending has been ending for some time and it is disastrous.”

It feels like you’re mourning something more complicated than just the terrible human cost of war there.

Ackerman: What was so disorienting about last summer, even outside the debacle of the withdraw, was this thing that had always been there was finally going to vanish. And what did that mean? It felt like you were saying goodbye to an old friend who you had a very complicated and dysfunctional relationship with over many, many years.

And because these wars were fought with volunteers, those who fight them always have a choice: to keep fighting or to make a “separate peace” for themselves.

It takes a lot of work to convince yourself that you’re done with it. And then you’re sucked back in and your separate peace shatters. Last summer was the collective shattering of thousands of separate peaces. And I don’t say that in some abstract way. I mean you’re sucked back into the war when your phone starts lighting up with people you know with photos of their entire families and they’re saying, “Please help us.”

The book tells the stories of you trying to help, but it also tells stories from your past about the people you reached out to, stories you’ve never told before about your time at war. Why tell these stories now?

I tell the story in five acts, because I think people need to understand Afghanistan, and I’d like to get people’s mind around Afghanistan if they’ve never paid attention to it. So the first act is Bush, then Obama, Trump, Biden, and the fifth act is the Taliban. And braided into that are five stories of five evacuation cases that I was involved in over the summer, a number of which pulled me back to certain relationships that I once had, because to get people out you are leveraging relationships.

So I’m writing about my time at CIA because a friend of mine who really put his neck on the line to get some people out was a CIA officer, and he and I have a multi-decade relationship. And one of the commanders of the infantry battalions at the airport, we went through training at Quantico together, so I talk about that history.

You also tell a story from Afghanistan about losing a comrade, and the question of whether or not to risk your surviving Marines to go back and recover his body.

I wanted to write about something that happened to me in Afghanistan many years ago, where I felt like, or still frankly question, whether or not I lived up to the ideal of “leave no man behind.” It’s a code in the U.S. military. A code as old as war. Homer writes about it, when Achilles kills Hector and drags his body back to his camp and Hector’s father comes to beg for the body of his son.

And as we left Afghanistan, our country, America, was basically asking all of its veterans who served in Afghanistan or anyone with a connection to Afghanistan to participate in this immoral act of leaving tens of thousands of people behind. What is the cost of that?

I remember talking with an Army veteran who told me, flat out, “My interpreter saved my life in Afghanistan. Why would I ever stop doing everything I can to help his family get out?”

After 20 years of war, 20 years of promises, you wind up with a debt. Nations do have moral debts, I believe that. And the question becomes what happens when the government decides that it’s going to forfeit its debts? Well, it fell on individuals. And that was the big scramble that you saw.

Given that everyone knew some version of this was going to happen, how did it get so bad?

The administration bet everything on the idea that there would be a decent interval. Meaning that we would withdraw and then maybe two years would pass, maybe six months would pass. If you look at Soviet withdraw to the collapse of the Communist government, that was several years. Same thing in Vietnam. The moment there was no decent interval and the administration had absolutely no contingency plan—that was it. The die was cast.

A common touch point in the book is the notion of betrayal. It felt like a betrayal of your comrades in arms when you left the service. A betrayal when the country ignores the wars it wages. A betrayal to have mismanaged the wars so badly and with such little accountability. And then the final betrayal is leaving so many behind.

What does the way we’ve conducted these wars say about our character as a nation?

Well…you’ve made me think.

For the first time?

(Laughs) Yeah. First time ever. In Green on Blue…

Your first novel, about Afghanistan.

The epigraph of Green on Blue is from Imam al-Bukhari, “Allah’s Apostle said, ‘War is deceit.’” So…war is betrayal. It’s hardwired into war, because what we are ultimately always betraying in war is our elevated sense of our humanity. “Thou shalt not kill,” the single most foundational rule of all civilization. So it doesn’t necessarily surprise me that the Afghan War ends in some type of betrayal. But it doesn’t take away or diminish the pain of it.

And it really made me look at the Vietnam guys a lot differently. I always thought they were more suspicious of us, because we were volunteers who kept going back to the wars. I really didn’t know that the skepticism sensed from them wasn’t actually skepticism. It was pity. They knew something I didn’t know yet—how wars end. With massive betrayal.

And with this war, communication technology meant that as the war ended Afghans you knew were directly reaching out, telling you how desperate things are. Meanwhile you’re using the same technology while you’re on vacation with your family—trying to be a father, trying to be a husband, trying to give your kids a childhood untouched by horror—desperately trying to reach anyone you can who can help get people out.

It was very important to me in the book to show my family. I wanted the reader to see the distance between these two worlds. I think the moral injury comes when everyone walks away, when the country that ostensibly sent you to war has said that they’re done with this and the cleanup is left to you. And I can only speak for myself, but I imagine this might include many other veterans feeling so angry that you’re the one that has to tell that Afghan interpreter who worked for the Americans for 6, 7, 8, 9 years that there’s nothing you can do for him and he’s on his own. How do you tell these people you can’t help them anymore?

One other thing that happens in the book is you get people out of Kabul, but then it’s not exactly clear what their status is going to be. I don’t know if you’re tracking the U.S. trained Afghan pilots who were stuck in holding camps in Tajikistan, only just recently moved but with the U.S. still failing to accept their cases for family reunification. So there’s the ongoing crisis of folks stuck in Afghanistan and then there’s the way the system is still not functioning for the people who got out.

The summer was clearly a debacle and the Biden administration just wanted this to go away. And the way you make it go away is you make the people involved in it go away. This limbo has come from a desire to not deal with the fact that, yes, we got people out but they’re sitting Tajikistan and in Uganda. In the U.S. some of them aren’t allowed to work so if there’s something we can do, it’s moving forward to expedite these people coming into the U.S., becoming citizens, and letting them work, particularly in a time where we have a labor shortage in the country. There’s no way to make everything right but there are certainly ways to behave more appropriately.

Discussing this frankly was difficult because certain people didn’t want to criticize the evacuation because they’d supported the withdrawal from Afghanistan and felt those two issues couldn’t be viewed separately, or because they didn’t want you to criticize the Biden administration.

Well, partisanship makes you dumb. Very early on, you saw a whole bunch of people who will tell you all day long that they’re about internationalism and standing up for the little guy, but the second they felt that the mishandling of Afghanistan in any way threatened their partisan team they were immediately on the other side.

Afghans are holding on to the wheel wells of C-170s and they’re falling to their deaths, there’s thousands of people at the gates, and they can’t get in and you want to say this is a success? The truth everyone can see is that this is a catastrophe.

One part of the book that I found fascinating and haunting was your discussion of how war functions in our in our national imagination, and how these wars differ from previous ones.

Wars have typically been experienced generationally. Vietnam, the Second World War, the First War. But, while 9/11 was a big moment and everyone remembers where they were on 9/11, it didn’t define our generation. But it has certainly defined me and defined many friends of mine. So we’re sort of a lost part of a generation rather than a lost generation.

Like the “Lost Generation” of World War I.

And I think it might be nicer to be part of a lost generation, where at least being lost is a common experience, whereas for us it’s sort of this outlier experience. It’s a very dangerous thing when wars are not experienced communally.

The book ends with the successful evacuation. But the story of last summer was the story of so many failures to successfully evacuated people. What should Americans be doing now?

There’s the Afghan Adjustment Act in Congress and there are many efforts individual citizens have undertaken, like hosting Afghans. All that is critically important. But I think we need to be cognizant of the way we went to war. With an all-volunteer military funded through a deficit spending, which in my belief led to a 20-year war.

We need to do some soul searching and ask ourselves, just like we asked ourselves about the draft after Vietnam—is this the healthiest way for a Republic to wage war?

It shouldn’t be easy for the United States to fight a war. War should be existentially painful for us, so the cost is high enough that we only go to war when we really need to.