A war on Christmas? Celebrations were once banned by pilgrims

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

GRAND RAPIDS, Mich. (WOOD) — Christmas Day has been historically relevant for centuries and the celebrations have changed over the years and differ between cultures. But did you know there was a time when celebrating Christmas was actually illegal stateside?

It’s true. Government officials actually worked to stop Christmas celebrations.

It all stems from our country’s first settlers — no, not indigenous Americans, the other ones. The pilgrims are known for the “first Thanksgiving” but many of them didn’t care for Christmas. It was given the nickname “Foolstide” because the celebrations more resembled the Bacchanalian ones from the Roman empire — raucous, gaudy and full of sex, alcohol and gluttony.

TRACES OF HOLIDAYS PAST

Peter C. Mancall, a humanities professor at the University of Southern California, wrote in The Conversation that the celebrations clashed with the Puritans’ strict ideals.

“For generations, the holiday had been an occasion for riotous, sometimes violent behavior,” Mancall wrote. “The moralist pamphleteer Phillip Stubbes believed that Christmastime celebrations gave celebrants license ‘to do what they lust and to follow what vanity they will.’ He complained about rampant ‘fooleries’ like playing dice and cards and wearing masks.”

Christmas Day is a unique date in history

Celebrations at that time held several concepts that sounded more like modern-day Halloween than Christmas. Many people wore costumes, and according to David F. Holland, a professor of New England Church History at Harvard, Christmas celebrations often had a precursor to trick-or-treating called wassailing.

“One of the distinctive features of a traditional English Christmas was very conspicuous begging or asking for food by people lower on the social ladder toward people who were better positioned, including something that might look a little like Halloween,” Holland told The Harvard Gazette. “You’d knock on a door, you would demand food or drink, usually an alcoholic drink. If the host did not provide what you had asked for then there was a cultural expectation that you would cause some mischief for the host.”

In the song “We Wish You a Merry Christmas,” do you recall the lyric about figgy pudding? The one that says, “We won’t go until we get some.” They meant it.

Sign up for the News 8 daily newsletter

Holland continued, “Sometimes this spiraled out of control into actual moments of violence or conflict. Christmas became associated with sexual licentiousness, the loosening of normal social mores.”

The Puritan crackdown on Christmas started in England, but the group had little influence over the revelries at that time. But when they made the trip west and founded the colonies, they held more control.

While the first Pilgrims were almost exclusively Puritan Separatists, later trips included people who were more interested in the financial prospects of the Americas and didn’t mind bringing their yuletide traditions with them.

“The early Puritan migration to New England was quite socially homogenous,” Holland said. “The early Puritan settlers didn’t want to bring the truly indigent with them from England. Nor did you have an aristocratic class. So, many of the early Puritan migrants represented a shared social position as well as a common religious commitment.”

Beyond Santa Claus: Exploring Christmas traditions from around the world

He continued, “The goal was to set an example for England. … The goal was to demonstrate what a godly community could look like and how God would bless and benefit that community: to be this shining example so that people in England would say, ‘Ah, that’s what we can become.’ If we do the same thing, we will receive similar kinds of divine blessings and we will prosper accordingly.”

CRACKING DOWN

The Pilgrims’ first Christmas came and went with little fanfare, but by the next year, William Bradford, the Governor of the Plymouth colony, put his foot down.

Historical accounts say that a group of non-Puritans fought against working on Christmas Day, saying it went against their beliefs. According to his journal, Bradford allowed them to have the day off, assuming they would celebrate privately in their own homes with prayer. But when he found them outside playing sports — including “stoolball” — he confronted them.

“(He) took away their implements and told them that was against his conscience, that they should play and others work. If they made the keeping of it (a) matter of devotion, let them keep their houses, but there should be no gaming or reveling in the streets,” Bradford wrote in his journal. (He wrote in the third person, referring to himself as “The Gov.”)

Bradford’s journals don’t recall any major issues around Christmas celebrations for the next several years, but decades later, the Puritan standard persisted and moved to crack down on any debauchery.

Rev. Increase Mather — the father of Cotton Mather, one of the leading proponents of the Salem witch trials — led the push against Christmas celebrations. According to Jonathan Beecher Field, a history professor at Clemson University, Mather believed the holiday emphasized pagan traditions and clashed with the Puritan worldview.

“The Puritans were not very concerned with a very scripturally based form of worship,” Field told WBUR. There’s no scriptural evidence for Jesus Christ’s birth on December the 25th. Christmas was added to Christ about 400 years after he was alive.”

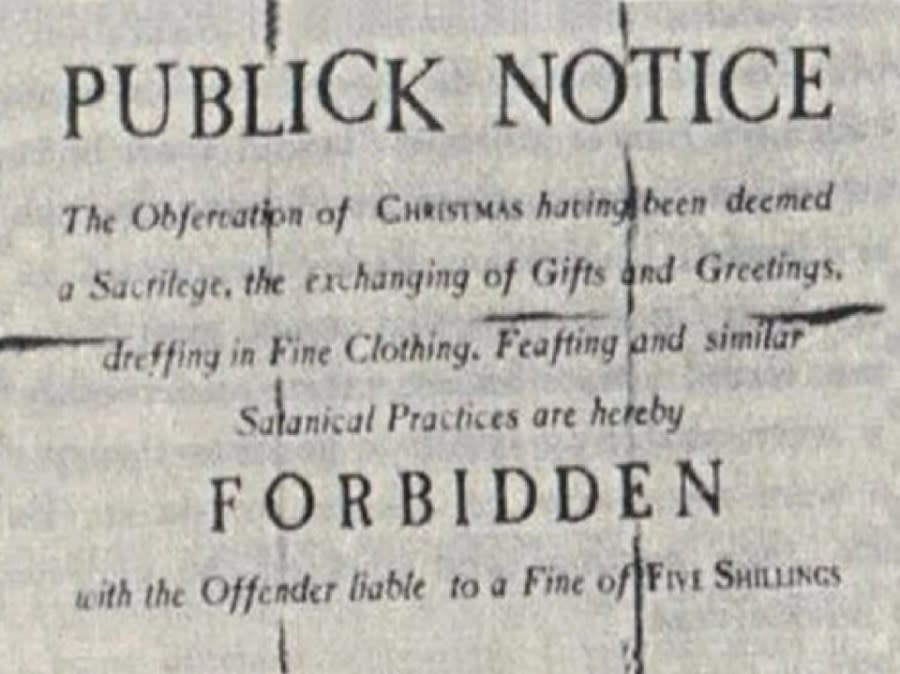

Mather deemed the celebrations highly dishonorable and excuses for drunkenness and debauchery. By 1659, the Massachusetts Bay Colony officially outlawed Christmas celebrations, stating any offenders could be fined up to five shillings — approximately $63 today.

Christmas Tree Ship crosses Lake Michigan, bringing holiday spirit, tradition to Chicago

Public declarations were posted across Boston announcing the news. It read, “The observation of Christmas having been deemed a sacrilege, the exchanging of gifts and greetings, dressing in fine clothing, feasting and similar Satanical practices are hereby forbidden.”

Eventually, the “Christmas Resistance” as Holland called it, faded. In 1681, the ban came off the books, but that didn’t usher in a wave of revelry.

“Christmas itself transforms into a more socially respectable, more religiously acceptable form, and as society itself diversifies and liberalizes away from those early Puritan commitments,” Holland said. “Through the end of the 1700s and into the early 1800s, it’s a very modest affair, something that looks more like Thanksgiving than a modern Christmas, with a little extra food and families gathering.”

He continued, “We start to see people writing music specifically for Christmas in the last couple decades of the 1700s; calendars and almanacs begin to consistently designate Christmas Day. So, these cultural markers show us that it is getting more and more acceptable and that the practice looks more and more familiar to us as something other than Carnival.”

For the latest news, weather, sports, and streaming video, head to WOODTV.com.