War protests, Black Panther Party: Yale alums reflect on Black student movement of 1970s

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

In 1970, Yale University's campus was one of many focal points of Black social and academic change – and tensions that had been building across the country over women's rights, the Vietnam War, the Black Panther movement and minority student representation came to a head on May Day of that year.

Demonstrators gathered in the college town of New Haven, Connecticut, to protest the trial of Black Panthers Bobby Seale and Ericka Huggins and call for their release. The party leaders were being tried in the murder of fellow member Alex Rackley – a presumed FBI informant.

Yale wasn't the only academic institution that was met with protests that year – among the most talked about is Kent State, where four students were killed. But Yale stands out as a place where thousands of protesters gathered and their voices were heard without major physical violence. Ultimately the charges against Seale and Huggins were dropped, and Yale in the late 1960s and early 1970s became a model of racial progress.

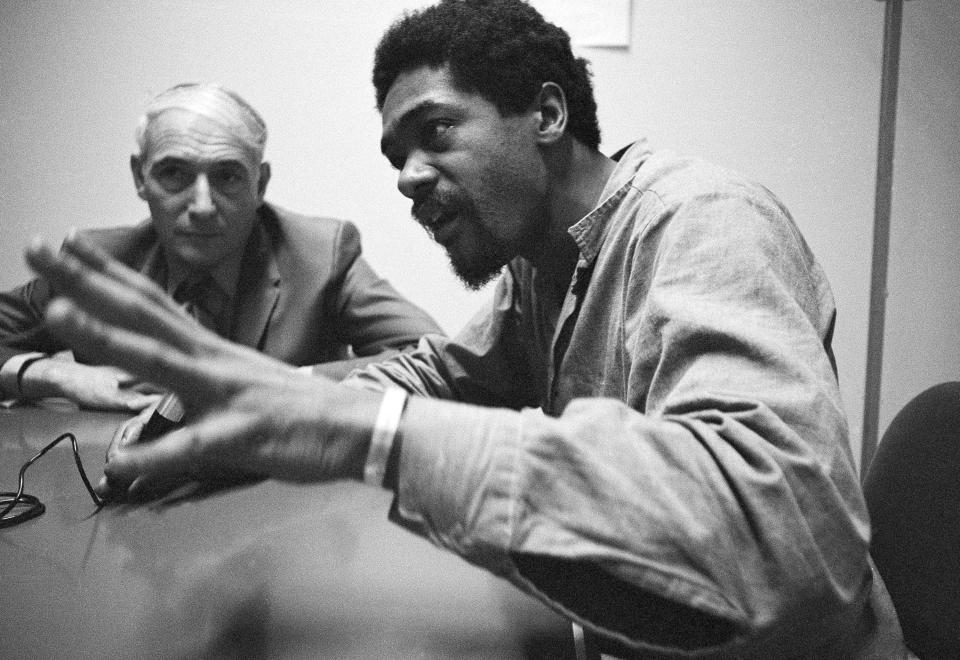

Two of the university's prominent Black graduates talk about that tumultuous year, the changes they made on campus, May Day and the push for progress.

— Eileen Rivers is projects editor for USA TODAY Opinion.

Kurt Schmoke

I entered Yale University as a freshman in the fall of 1967. At that time the university was an all-male institution. It was an institution bound in tradition, somewhat culturally constrained and on the cusp of major change led by an activist president. Of the 1,000 men admitted in that class, only about 30 were African American. The experiences of those African Americans before, during and after Yale varied widely.

I was admitted as a scholar athlete expected to play on both the football and lacrosse teams. Because of my involvement with sports and because I had come from an all-male public high school, my transition to Yale was relatively easy.

But political and social factors soon changed the focus of my activities on campus.

I joined several other students to demand that the university provide child care services for campus dining hall workers. The day care center we established is still in operation more than 50 years after our graduation.

Wayne Dawkins: NYPD's first Black female commissioner is a historic first, with historic challenges

The university had to address issues relating to Vietnam War protests, the controversial trial of Black Panther leaders, the negative reaction of influential alumni about Yale President Kingman Brewster’s commitment to diversity, and the demands of Black students for a more inclusive curriculum. I was involved with all of those issues, as were my classmates.

Yale's Black Student Alliance joined with senior administrators to ensure peace on campus when thousands of demonstrators descended on New Haven in May 1970. Later, we worked to ensure that all voices were heard regarding the military presence on campus. We built on the work of African American students who preceded us to create a major in African American Studies.

In 1969 Yale admitted women to the undergraduate college, and African American women soon became major forces for change at the university.

Columnist Connie Schultz: How potholders got me thinking about racism, my father and the whitewashing of US history

Women and men of color who attended Yale have become community leaders, and I continue to promote the school as a welcoming place for students of color.

Hopefully, today’s students at Yale will carry the lessons learned at the university about the importance of diversity, equity and inclusion as they become future leaders in our communities.

Kurt Schmoke is a former mayor of Baltimore and has served as president of the University of Baltimore since 2014. He is a 1971 graduate of Yale.

Constance Royster

In September 1969, I was one of the first women to attend Yale as an undergraduate student in its 268-year history. There were 575 women (freshmen through juniors) in the first cohort, and about 40 of us were Black. In my sophomore class, only eight of us were Black.

We joined a college campus of about 4,000 mostly young white men as then-President Kingman Brewster had vowed to graduate 1,000 male leaders each year – the first of his indelible statements at the time.

I knew New Haven and I knew Yale well. But the Yale I knew was downtown, white and mostly closed off except for workers. My grandfather (along with his brothers, cousins and friends) immigrated to New Haven from Nevis in the British West Indies to work at Yale in the 1900s.

Rachel K. Paulose: Behavior of attorney representing man accused of killing Arbery shows systemic racism in court

The Afro-American Cultural Center and the Black Student Alliance were active places of camaraderie. They were also crucial as May Day 1970 – during which thousands of demonstrators descended on Yale to protest the trial of Black Panthers Bobby Seale and Ericka Huggins – approached.

These places were, perhaps understandably, mostly run by men. But my female classmates stepped up and became leadership voices – lawyer and minister Shirley Daniels, former NBC executive Vera Wells and U.S. Rep. Sheila Jackson Lee come to mind. We are all friends to this day.

In the months before May Day 1970, my Black classmates and friends – including late lawyer William “Bill” Farley, Ralph Dawson (a New York attorney and civil rights advocate), Kurt Schmoke (who would eventually become mayor of Baltimore), Henry Louis “Skip” Gates Jr., (now star of PBS' "Finding Your Roots") and others – took the lead not only in drawing attention to the reality of Black Americans in the criminal justice system but also pushing for peace in the incubator that was New Haven.

Protests were happening at campuses all over the country, including Harvard and Columbia, and many were violent.

The women’s movement, the Black radical movement and the white radical movement were all happening at the same time on campus. The world outside was also exploding – cities were burning, students and demonstrators were being beaten and killed, the civil rights movement was nationally active, the Vietnam War was raging, and President Richard Nixon and Washington leadership could not be trusted. What we as students cared about was that justice and fairness prevailed at the Black Panthers trial, and that Yale and New Haven did not burn down. There were tanks in the streets, and the National Guard was all around us.

Columnist Suzette Hackney: Finding my family's history in Brunswick, Georgia, where Ahmaud Arbery was murdered

Yale and New Haven did not burn. There were relatively few arrests or injuries on campus. But a generation of Yale students got the greatest civics lesson of any that could possibly be given during four years on campus.

We had several things going for us at Yale: Chaplain William Sloane Coffin, a prophet in my opinion, had probably long prepared us for this crisis. The Center for Service and Advocacy, Dwight Hall, was neutral ground for planning and execution (and that's where many of us had gained our leadership knowledge). Yale's president was very progressive and stated, referring to Black Panthers on trial, that he doubted that a Black man could get a fair trial anywhere in the country.

Most of all, we had the greatest collection of young Black male and female classmates gathered at the right time, in the right place to lead. We also had smart white classmates who knew enough to step back and let the Black students get the job done.

Constance Royster is a retired lawyer and Yale Divinity School director of development. She counsels nonprofits on governance best practices. Her story as one of the first women in Yale College is told in "Yale Needs Women" by Anne Gardiner Perkins. She is a 1972 graduate of Yale.

You can read diverse opinions from our Board of Contributors and other writers on the Opinion front page, on Twitter @usatodayopinion and in our daily Opinion newsletter. To respond to a column, submit a comment to letters@usatoday.com.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: War protests, Black Panther Party: Yale alum on Black student movement