A war travelogue: Two Florida photographers recount harrowing trip to document the Ukraine war

David Graham and Allan Mestel stopped for a break on the side of the road near Donetsk, Ukraine, last summer when Graham pointed out a faded green piece of plastic – remnants of an exploded land mine.

“It looks like a toy,” Graham told Mestel, his colleague in the journalistic endeavor Portrait Ukraine 2023, which can be seen on the Spotlight Ukraine website.

“It looks like a toy; I was like 'Allan that’s one, right here,’” Graham recalled. “It was safe, it had already exploded but just this little piece of green plastic would take your foot off.”

Mestel added, “I think that was one of the most dangerous aspects of what we were doing the whole time we were in Donetsk: there were signs up, ‘Watch out for mines.’”

Graham, 56, and Mestel, 61, both photographers from Sarasota, Florida, were in the midst of a three-week journey through Ukraine, as freelance journalists and documenting the war's impact.

They also sent regular dispatches to Spotlight Ukraine, a passion project website operated by Christine Mariconda, a marketing professional now based in Sarasota.

At least 17 journalists have been killed in Ukraine since the Russian invasion began in February 2022, according to the Committee to Protect Journalists.

Mestel and Graham have taken on the risk more than once. Their trip in late August and early September was Mestel’s third and Graham’s second.

Along the way, soldiers they traveled with were constantly urging the two men to stay on the paved areas.

“There were unexploded mines all over the place,” Graham told the Sarasota Herald-Tribune, part of the USA TODAY Network, adding, “Somebody lobs a shell and all of a sudden, there's 200 more unexploded mines around.”

One of the more sobering instructions the two men received from their military escort was on the importance of having a tourniquet kit attached to their clothing. “'Make sure they’re somewhere you can reach them one-handed, with either hand,'” they were told.

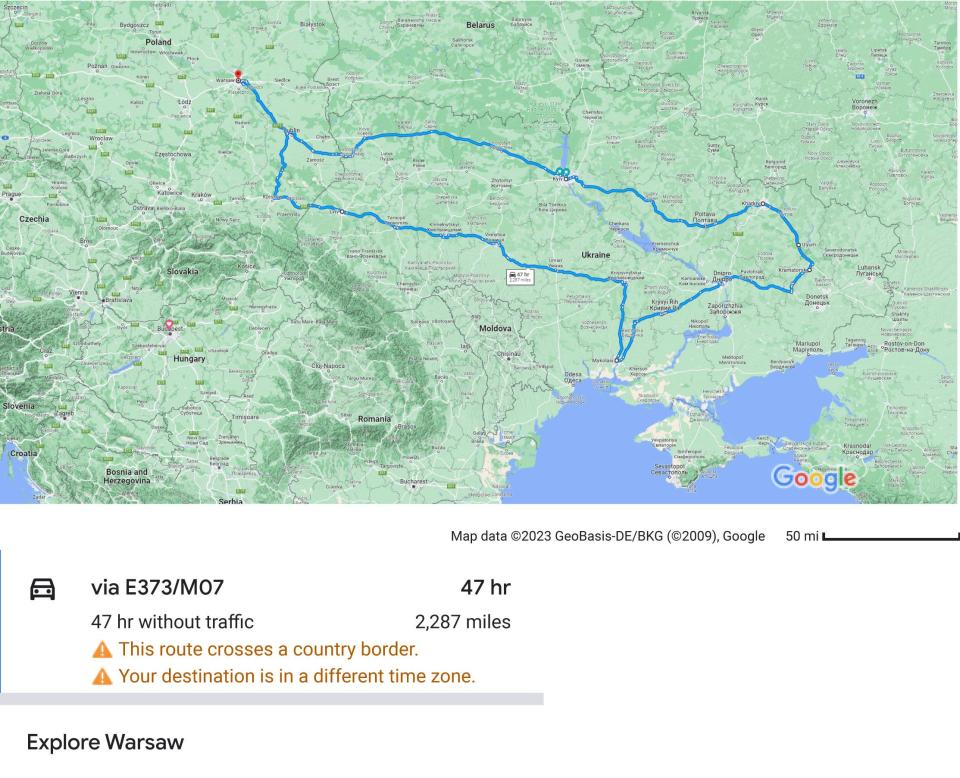

A journey of 2,287 miles from Warsaw through Ukraine

Mestel and Graham met through the Sarasota photographic community.

Originally from Canada, Mestel started in advertising as a director and editor of TV commercials in Toronto. He frequently pursues documentary projects about the plight of refugees and immigration and co-founded the Sarasota-based nonprofit Streets of Paradise in 2018 along with his wife Robyn Richardson and community activist Greg Cruz.

Graham, a computer specialist with the Sarasota County School District, is a popular wedding photographer and photography instructor

Prior to their late summer trip, the two were talking and Mestel expressed an interest in getting closer to the conflict.

“He had this passion to go back, I was looking for a contract or something to go back or an excuse to go back,” Graham said.

In turn, Mestel said Graham’s experience gave his wife Robyn a little more comfort that they would return home unharmed. While the trip was Mestel’s third to Ukraine after Russian troops invaded the country in February 2022, it was Mestel’s first time venturing close to the front lines of a conflict.

Graham, who worked as a contractor for a number of federal agencies and commercial businesses, had previous exposure to a wartime environment in the Middle East. He also went to Ukraine in March 2023 to help the Ukrainian military with training.

“The concept was to go there and capture portrait-style images of people that were representative of the war in multiple situations – civilians, military, first-responders,” Mestel said. “Anyone we ran into who was impacted significantly by the war I wanted to shoot portraits.”

Graham recorded the trip through roughly 100 hours of video and interviews that he plans to turn into a 60-minute documentary.

Between Aug. 28 and Sept. 9, 2023, the two traveled 2,287 miles – from Warsaw Poland, as far east as Kramatorsk, near the combat zone, and back to Warsaw.

Mestel’s first trip to Ukraine in March 2022 and second trip that summer were both spent documenting the humanitarian efforts, mostly in western Ukraine.

Mariconda saw photos from Mestel’s July 2022 trip in a local magazine and reached out to him about working together. Mariconda wanted to do something for Ukraine, to keep the story in the public eye as the conflict receded from breaking news.

“That was the seed for Spotlight Ukraine, to share personal stories that would connect with people,” Mariconda said.

Ensuring awareness of the Ukraine war does not fade

From Mariconda’s perspective, the stories Graham and Mestel can share help keep the victims in the public's consciousness.

“We would continue to share personal stories that would connect with people that – as time goes on and the main news outlets lose focus and interest – we would continue to share stories that would keep people engaged,” she added. The website serves as a link to nonprofits funding the relief efforts in Ukraine.

Mariconda saw a synergy between her goal and the work Mestel produced last year – now known as Portrait Ukraine 2022.

“When I’m shooting photo journalistically,“ Mestel said, “I like to capture images that allow people to have an emotional connection with individuals.”

On Mestel’s first two trips, in March and July 2022, he was documenting the living conditions of refugees from fighting in the eastern portion of Ukraine, though the whole country was on a war footing.

Capturing three events a day

It takes about two days to get from Sarasota to Ukraine, including a drive to Miami, flight to Warsaw and then an 18-hour train ride from Warsaw to Kyiv that includes a six-hour stop at a facility near the border, where the undercarriage of the train cars could be swapped out to travel on tracks in Ukraine that still match the gauge of the Soviet rail system.

For this trip, they rented a white Renault SUV that bore signs with both the Canadian and U.S flags and the word press spelled out in English and Ukrainian, and hired fixer/guide Denis Rumiancev to help them.

Neither Graham nor Mestel speak Ukrainian.

In Kyiv, people they encountered could speak English and Polish but the farther east they traveled, they relied more on Google Translate to communicate with they encountered.

“It works,” Graham said. “Not only do you get your point across but they get the gist of what you’re trying to do.”

Both men had applied to the Ukrainian army to receive press credentials and checked in with local press offices at every major city where they stopped.

Rumiancev – who can communicate in four different languages – worked his connections to find different aspects of daily life that they could document.

“It was absolutely incredible the amount of contacts he had,” Graham said. “We were doing about three things a day.

“One morning we had a school opening and then we had the gay pride parade and then we went to a place that rescued 15,000 animals – and we got it all done in one day.”

Mestel added that they had little down time during the three-week trip.

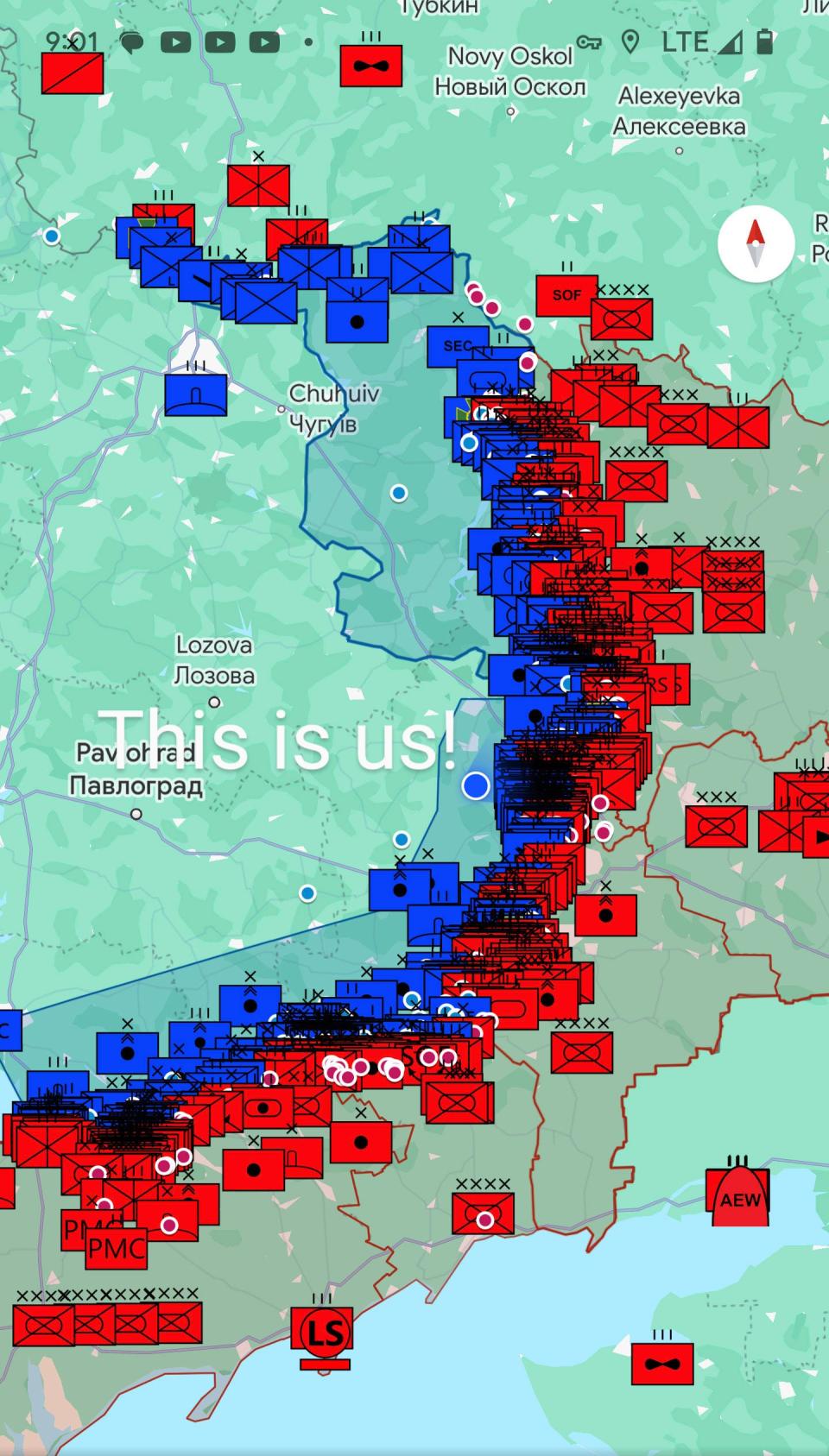

“I think we did actually go from rescuing puppies right to the front line,” he added.

‘Boom, Boom, BOOM!’

Graham recalled that on their first night, at 5 a.m. in Kyiv, they experienced a barrage of rockets – one of which blew up a big building.

“We got rocketed in every city,” Mestel added “Every city, every night there were rockets impacting.”

While Mestel had been in some potentially dangerous situations documenting the plight of refugees in Ciudad Juarez, Mexico, the trip to Ukraine marked the first time he worked close to active gunfire.

“The entire time we were there, we never stopped hearing Russian shellfire – some of it distant, some of it much closer,” Mestel said.

Every night, Mestel said, they heard “big booms.”

“There was one time when it sounded like they were walking the shells towards us – that got my attention – when you heard ‘Boom,’ ‘Boom,’ ‘BOOM!'”

Chasiv Yar, one village over from Bakhmut – was one of several places where Mestel and Graham shadowed the nonprofit Ukrainian Patriot – a last-mile organization founded by dancer Lana Nicole Niland that delivers both military and humanitarian aid.

Ukrainian Patriot volunteers dug a new well, so residents could have access to running water for the first time in a year-and-a-half.

A road race in combat

Mestel drove their white Renault SUV between destinations, with members of their military escort urging them to keep up at an 80- to 100-mph pace.

“We were literally doing rally-style combat driving from one place to another,” Graham said.

Mestel’s fast-paced driving continued even when they weren’t with military escorts. One time Graham noted, he beat the GPS-suggested travel time by 45 minutes. In one small town, they were pulled over for speeding by local police.

Mestel gave the officer all of his papers, including his driver's license, Canadian passport and Ukrainian driving permit.

The officer looked at his paperwork and then consulted his supervisor.

“I think they didn’t know what to do with me so he came back and said, ‘Have a nice day.’”

One country, two fronts

In Kharkiv, Mestel said, only one elderly woman still occupied her apartment in an otherwise empty block of apartment buildings.

“There’s a hardcore group of people – mostly elderly – who won’t leave,” Mestel said.

In contrast, Mestel added, “The west is operating basically as normal – except for the rocket fire every night – it's literally a lottery as to whether your building is going to be hit.”

Graham noted that a large rocket may damage one structure but not the next, creating a situation where “there’s a bombed-out school and right next door, a store was open.”

There are other contrasts that still haunt both men.

Near Izyum, they saw the bodies exhumed from a mass grave site of roughly 455 people that Ukrainian officials are trying to identify, “People who were executed and buried by the Russians in unmarked graves inside the forest,” Mestel said.

Meanwhile in Lviv, roughly 44 miles from the border with Poland, they visited a military cemetery, “and they can’t build graves fast enough,” Graham added.

While their press credentials helped, Graham said it did take some time to build up a level of trust with the people they talked with.

Graham noted that everyone was kind and expressed a fear that the Russians wanted nothing less than to exterminate them.

“The main thing we heard when we were there,” he said, “was they were so happy that we were there to tell their story, because they were afraid people were going to forget them.”

This article originally appeared on Sarasota Herald-Tribune: A trip to Ukraine allows Florida photographers to capture war images