A warming planet is pushing hurricanes north and deeper inland. What that means for NC

Multiple named storms and tropical waves have recently formed and have coastal residents, including those in the Cape Fear region, keeping a close eye on the tropics as we head toward what is historically the most active few weeks of hurricane season.

But research is mounting that it's no longer just homeowners near the coast or those south of the Mason-Dixon Line who have to worry about hurricanes or even strong nor'easters from bringing damaging weather conditions to their front door.

Heikki Vesanto, manager GIS data science with LexisNexis Risk Solutions, said there are many variables that factor into where and how strong hurricanes become.

"But at the root of it we do see climate change," he said, noting that the changing climate is leading to more intense hurricanes and expanded areas that can support these stronger storms.

As the planet and particularly the oceans warm as more and more heat-trapping greenhouse gases are pumped into the atmosphere, scientists warn that tropical storms have the potential to grow in size, strength and reach as they draw fuel from increasingly hot waters.

GETTING BUSY As the tropics continue to sizzle, what will the rest of 2023 hurricane season look like?

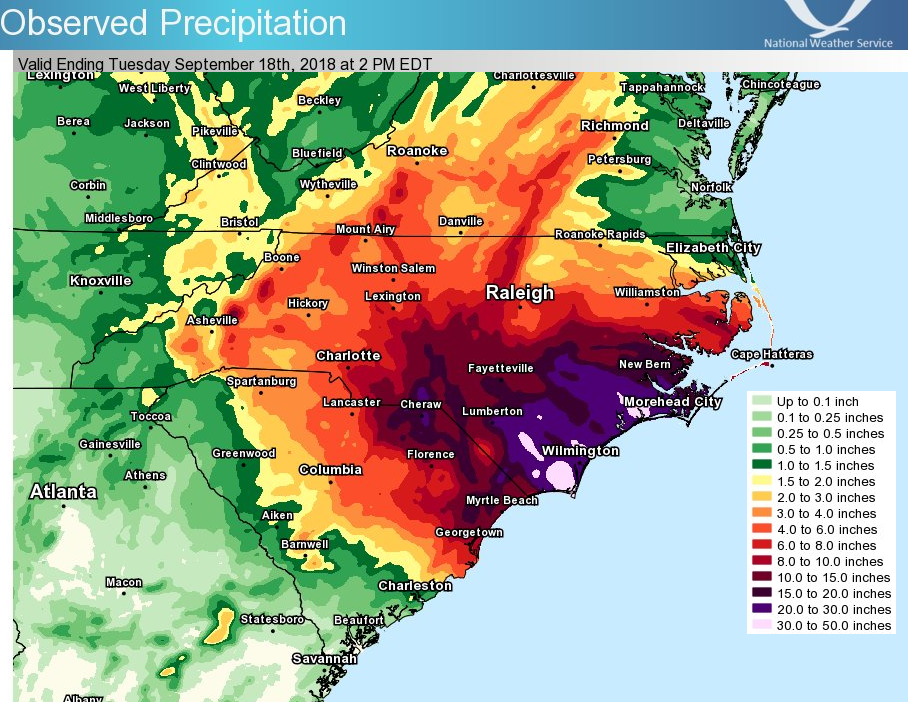

Hurricanes also are becoming physically bigger, impacting more of an area at once. They also are able to carry that power farther inland, bringing areas that used to be safe from hurricane-strength winds and devastating rains − since as temperatures rise, warmer air carries around more water vapor − in danger of being in the firing line.

Finally, powerful hurricanes are pushing farther north along the Eastern Seaboard as they ride the increasingly warm waters up the coast. The result is areas that are generally safe from strong hurricanes, like the Mid-Atlantic and New England areas, are getting battered. In September 2022, the remnants of Hurricane Fiona hammered Canada's Nova Scotia with coastal wind gusts that reached more than 100 mph. According to the Insurance Bureau of Canada, Fiona was the most costly extreme weather event ever recorded in Atlantic Canada and the tenth largest in Canada in terms of insured damages.

Dr. Michael Mann, professor with the Department of Earth and Environmental Science at the University of Pennsylvania, said 2021's Hurricane Ida and the devastating flooding it did all the way to Philadelphia and into the Northeast after forming in the Gulf of Mexico is a prime example of these more intense storms maintaining their tropical characteristics for much longer after making landfall.

"But there’s also evidence (including some of our own work) that the change in prevailing wind patterns associated with human-caused warming is leading to more northerly trajectories of storms, away from the Southeast and toward the Mid-Atlantic and Northeast, and we seem to be seeing that too," he said via email.

'Unavoidable financial impacts'

A report released earlier this year by the First Street Foundation echoed the dangers posed by these hurricanes as they push into areas where people aren't used to and buildings aren't often built to handle powerful storm impacts.

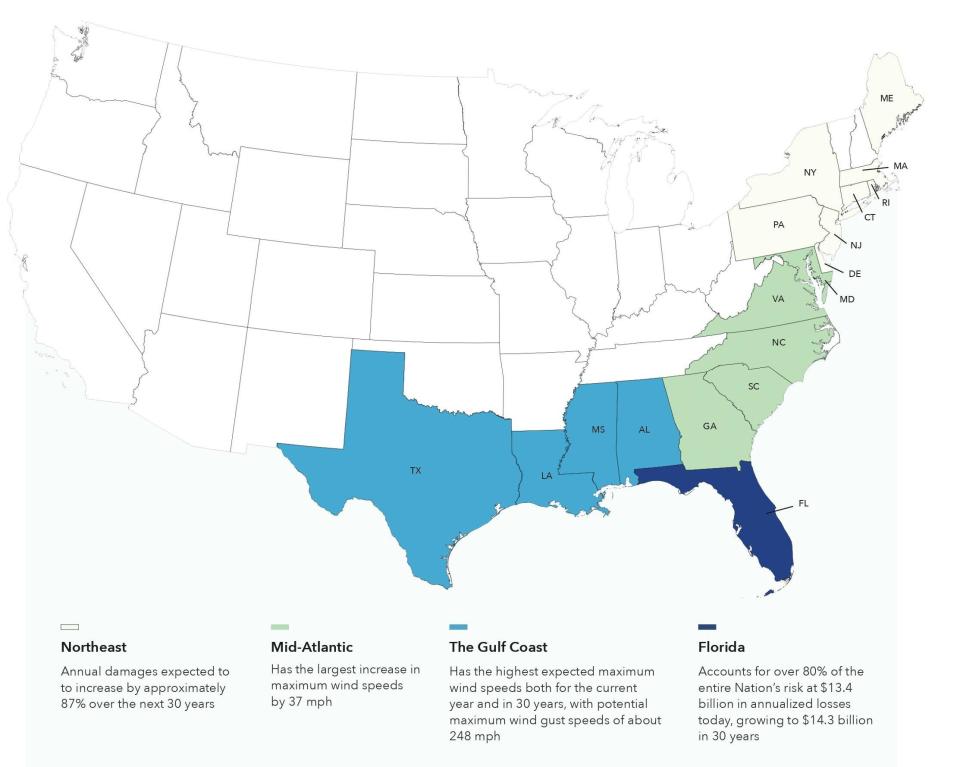

Crunching together computer modeling of hurricane tracks, high-resolution topographical information and property data, the study forecast wind-risk changes and damage estimates for much of the Eastern U.S. from these more powerful storms in the coming decades.

Not surprisingly, the report found the Florida and Gulf Coast communities will continue to have the largest potential for economic loss from hurricanes. The shift in location and strength of hurricanes in Florida alone results in the number of properties that may face a Category 5 hurricane jumping from 2.5 million in 2023 to 4.1 million by 2053.

The study also found that inland regions away from the coast and states that historically have rarely seen hurricanes would be at greater risk. For example, the report says that by 2053 all of North Carolina will be at risk from damaging wind speeds, with some areas in the Mid-Atlantic seeing maximum wind gust speeds increase by 37 mph and corresponding damages increase by 50.3%.

Overall, the report found that in the next 30 years 13.4 million properties in the U.S. will be exposed to a level of tropical storm or higher wind risk that they do not currently face today.

“Compared to the historic location and severity of tropical cyclones, this next generation of hurricane strength will bring unavoidable financial impacts and devastation that have not yet been priced into the market," said Matthew Eby, First Street Foundation's founder and CEO, in a release accompanying the report's late February release.

Weighing risk while determining rates

The impacts of these changing weather conditions are likely to have profound impacts on insurance markets, and not just in areas like Wilmington that are seeing regular significant jumps in their rates as companies factor in their vulnerability to insuring properties in "hurricane alley."

George Hosfield, senior director, home insurance at LexisNexis Risk Solutions, said historically insurance companies look at past performance to see what's going to happen in the future when determining rates. But in a world warped by climate change, that future is looking a lot more risky for insurance companies − and rates are rising in response. That includes rates in areas where property owners might feel they're being asked to shoulder some of the risk of consumers living in more exposed areas, like at the coast.

RISING RATES Insurance on NC beach rentals is going up again, potentially by a lot. Here's why.

RATING THE RISK Plan to assess risk of climate change on insurance, including in NC, courts controversy

If the risk is deemed to be too great, or state regulators balk at allowing insurance companies to charge rates that allow companies to cover their potentially liabilities, then insurers will pull out of a market. That's what's happening in Florida and Louisiana due to concerns over hurricane exposure and in California due to the risk of wildfires.

Hosfield said property owners can mitigate some of the risk posed by the storms of the future by getting flood insurance, even if they're not in a historic floodplain. States can also prepare for tomorrow's weather by strengthening building codes, although North Carolina legislators recently rejected plans to strengthen the state's residential building code over concerns it would price new homebuyers out of the market, and making smarter land-use decisions.

"When it comes to recovery, do we continue to rebuild the exact same home in the exact same spot, which is what we've historically done," Hosfield said.

With much of the Earth's future warming already baked in thanks to decades of massive greenhouse gas emissions, researchers know change is coming. But Vesanto and Hosfield said it won't happen overnight, and means there's still time for us to get prepared and adapt if needed.

"We're not really seeing a full picture of it yet," Hosfield said. "It will be a gradual change."

Reporter Gareth McGrath can be reached at GMcGrath@Gannett.com or @GarethMcGrathSN on Twitter. This story was produced with financial support from 1Earth Fund and the Prentice Foundation. The USA TODAY Network maintains full editorial control of the work.

This article originally appeared on Wilmington StarNews: Climate change hurricanes stronger tracking north farther inland in NC