Washington did it on horseback, Obama on social media: How presidents connect with the public

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

The White House is a bubble, insulating presidents behind layers of security, scheduling and staff. But our chief executives have always struggled to stay connected to citizens in a meaningful way – even as a growing nation has made leaders more remote, and technology and our changing culture have demanded a more personal presidency.

For George Washington, staying connected meant riding 1,700 miles on horseback and in carriages to visit every state of the new nation – attending his share of balls, receptions and banquets, to be sure, but also spending time with citizens in taverns, on front porches, and in dining rooms. And when he wasn’t out traveling, late afternoons were sometimes set aside for meetings with public callers, and evenings for dinner parties with invited guests.

The toughest audience of the year: How the White House Correspondents' Association dinner became a political, social showcase

America's pastime is White House staple: President Bush's first pitch, FDR's Opening Day record: Baseball plays major role in US history

President Washington also began a tradition of New Year’s Day open-door receptions. For more than a century after, Americans lined up in the January cold to greet their president at the White House. Thomas Jefferson was the first president to shake hands with guests instead of bowing – which could become brutal, as numerous presidents learned after hours of handshaking left their hands pulped. (John Tyler was so bruised after one session that he could not hold a spoon for days.)

Andrew Jackson made the White House an open house

When Andrew Jackson opened the doors even wider at his inauguration, dignitaries and citizens alike flooded into the White House, standing on upholstered furniture and spilling food and punch bowls, breaking crystal and grinding food into the carpet. (To lure the revelers back outside, tubs of whiskey punch were set out on the White House lawn.)

In the final weeks of the Jackson presidency, a 1,400-pound block of cheese was hauled into the White House’s main foyer for an open house. Thousands of citizens once again streamed through doors (and windows) to nosh and talk – and leave behind slippery carpets and odors that lingered for months.

CNN hosts Trump town hall: Blaming CNN for hosting a Trump town hall gives Republicans a pass

Do we really want Biden vs. Trump again? Americans need a third choice for president.

Abraham Lincoln was accessible by nature, giving so much time to receptions and visiting hours (he called them his “public-opinion baths”) that his staff urged him to cut back. “Though the tax on my time is heavy,” he said, “no hours of my day are better employed than those which thus bring me again within the direct contact and atmosphere of our whole people.”

Lincoln was clear-headed about the price of these conversations – but also the payoff. “Many of the matters brought to my notice are utterly frivolous,” he said, “but others are of more or less importance, and all serve to renew in me a clearer and more vivid image of that great popular assemblage, out of which I sprang.”

Lincoln’s 1863 New Year’s Day reception was bookended by history: he came downstairs from his office, where he had been finishing edits to the Emancipation Proclamation – which he signed later that day, after mingling with the public for three hours. (A year later, the 1864 New Year’s Day reception was the first ever to include Black guests, the Army’s first Black physician and his assistant.)

Handshakes at train stations became handwritten letters – then tweets

As the United States grew larger and more far-flung, getting outside the White House bubble took more time and effort. Trains allowed Grover Cleveland to crisscross the Midwest and South for 23 days in 1887, addressing tens of thousands of people – but personal interactions were often limited to handshakes at the train station. By 1932 the dawning mass media age (and growing security concerns) brought the New Year’s Day receptions to an end.

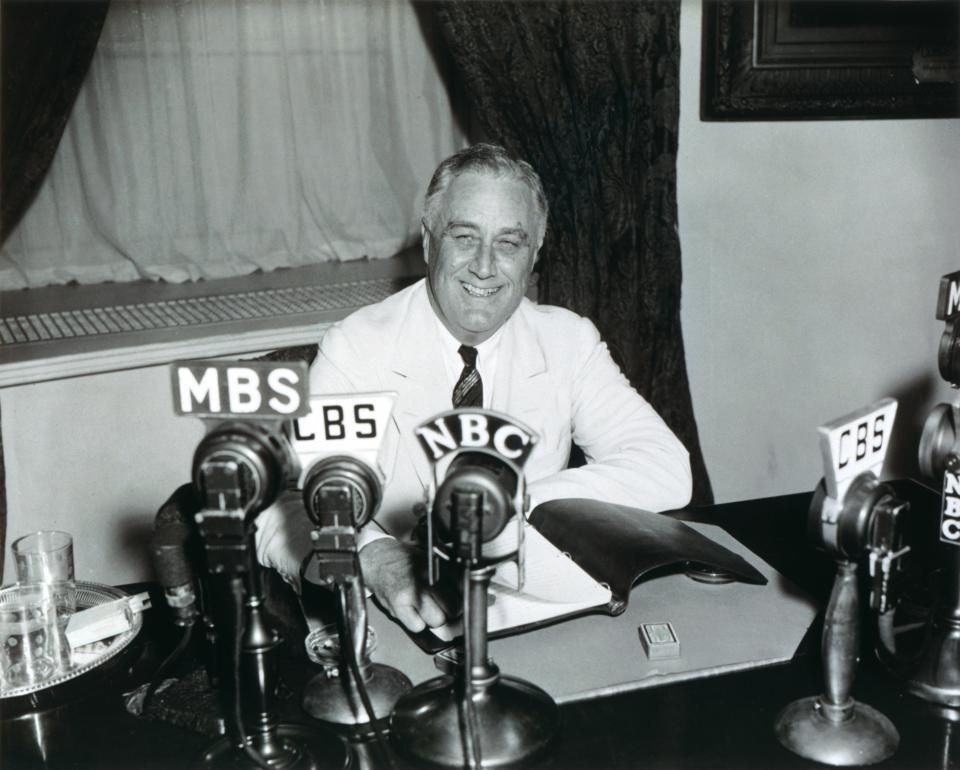

But even as Franklin Roosevelt moved presidential communications on to a far larger stage with his radio addresses – some of them tellingly dubbed “Fireside Chats” to evoke an intimate conversation – he also sparked a new birth of individual communications with the American president. When Roosevelt closed a radio address during the anguish of the Great Depression by inviting listeners to write to him about their troubles, a half-million letters came pouring in, turning the White House mailroom into a fire hazard.

That mailroom has grown busier ever since, receiving thousands and thousands of letters – a colossal test for any leader wanting to retain some sense of individual contact. President Reagan would stop by the mailroom to look through what was coming in, sometimes answering letters personally on weekends. President George H.W. Bush was famous for his many handwritten notes, sometimes to people he’d just met, and Bill Clinton was given a stack of mail every few weeks to read through.

Opinion alerts: Get columns from your favorite columnists + expert analysis on top issues, delivered straight to your device through the USA TODAY app. Don't have the app? Download it for free from your app store.

President Obama had his staff put ten letters every day into a purple folder. A child with a father in prison wanted to learn more about the criminal justice system. Someone sending in a copy of their medical bills. Obama answered many by hand, and sometimes the stories he read made it into his speeches.

Email and social media have multiplied these challenges. Presidents can still answer letters and hold town hall events, but they must constantly innovate to keep up with internet age communications – and an American population that has grown from 4 million in George Washington’s day to 330 million today. During his second term, Obama called back to President Jackson with a 21st century “Big Block of Cheese Day,” where administration officials answered questions on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, and Tumblr.

The presidency is adjusting yet again to a communications revolution, even as presidents try to focus on our most important national and global problems. But democracy is also a 1:1 exercise. One of the supreme political challenges of our era is how our leaders can keep hearing us as individuals, one human voice at a time.

Stewart D. McLaurin, a member of USA TODAY's Board of Contributors, is president of the White House Historical Association, a private nonprofit, nonpartisan organization founded by first lady Jacqueline Kennedy in 1961.

More White House history:

White House history is Black history: This is some of that story

Christmas trees and Hanukkah celebrations: Evolution of holidays at the White House

Trail of Tears to a Tribal Nations Summit: White House's role in Native American history

You can read diverse opinions from our Board of Contributors and other writers on the Opinion front page, on Twitter @usatodayopinion and in our daily Opinion newsletter. To respond to a column, submit a comment to letters@usatoday.com.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: FDR's Fireside Chats to Obama's tweets: How presidents talk to public