Washington National Cathedral moves toward healing by removing Confederate symbols

During a recent visit to Washington, D.C., I spent hours in the Washington National Cathedral, where I found an abundance of personal peace, national history and exquisite artistry.

I also found incredible joy in viewing the majestic edifice’s newly installed “Now and Forever Windows”that pay homage to the ongoing resilience and march for racial justice of Black Americans.

World-renowned artist Kerry James Marshall designed the new glass-stained windows to replace windows installed in 1953 that honored Confederate Generals Robert E. Lee and Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson.

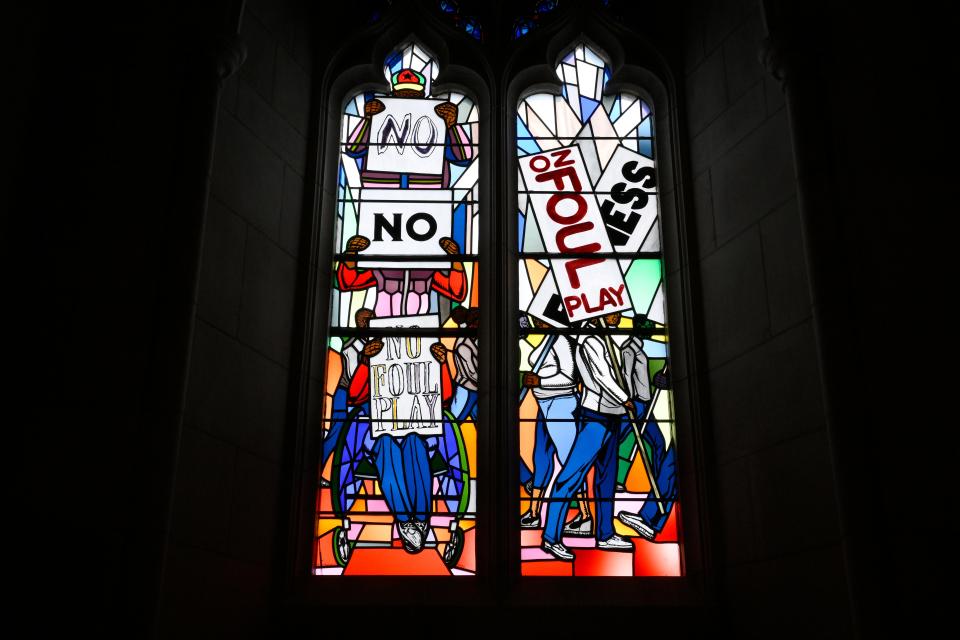

Now occupying those same window bays are vibrant and colorful glass panels that depict people of color protesting and carrying signs that read “Fairness” and “No Foul Play.”

“Through this new addition to the cathedral, we hope to tell a broader, more inclusive story of American history,” Cathedral literature says of the new windows. “In this House of Prayer for All people, we want to tell the stories of all people.”

Amen!

Confederate Reckoning series: Teaching accurate, comprehensive history strengthens American society | Editorial

How the decision was made to remove Confederate symbols

The Washington National Cathedral was conceived to serve as a great church for national purposes, though it is part of the Episcopal Church.

Built over 83 years of 150,000 tons of Indiana limestone, the Gothic Cathedral has 231 stained-glass windows, among other extraordinary art and architectural features.

It has been the site of funerals for national leaders, including four presidents. Each year, the cathedral gathers 160,000 worshipers with 1,500 worship services.

The move to replace the Lee-Jackson windows started in 2015 after the massacre of nine Black members at Mother Emanuel AME Church in Charleston, S.C., by a white supremacist gunman.

After that tragedy, the dean of the cathedral called for the Confederate windows to be removed. A committee was formed to study the issue and make a recommendation. In 2016, the Cathedral removed Confederate battle flags from the windows.

Then in 2017, white supremacists violently protested the removal of a statue of Robert E. Lee in Charlottesville, Va. A person was killed during that troubling “Unite the Right” rally. A decision was made to permanently remove the windows that honored the two Confederate generals. The Lee-Jackson windows were deconsecrated and removed.

Column by Lynn Norment: Advice from sisters who know: What you and every woman should know about breast cancer

Why the Lee and Jackson windows told a false narrative

During this time and since then, there has been a national reckoning in regards to confederate statues and other such monuments that have served as dreadful reminders of how Black Americans were mistreated during slavery and since then.

Many monuments of Confederates and slaveholders have been dismantled, including several in Memphis. It is heartwarming to know that the National Cathedral played a part in helping the nation move forward in creating a sanctuary where we all can worship in peace.

In a public statement, a Cathedral official argued that celebrating the lives of enslavers Lee and Jackson with stained-glass windows did not advance “healing and reconciliation,” as former cathedral leadership might have hoped.

“Simply put, these windows were offensive, and they were a barrier to the ministry of this cathedral, and they were antithetical to our call to be a house of prayer for all people,” Randolph Marshall Hollerith, the current dean of the cathedral, said during the dedication of the new windows.

He also said the original Lee-Jackson windows told a false narrative, extolling two individuals who fought to keep the institution of slavery alive in this country. “They [the Lee-Jackson windows] were intended to elevate the Confederacy, and they completely ignored the millions of Black Americans who have fought so hard and struggled so long to claim their birthright as equal citizens.”

Kerry James Marshall was the artist chosen to create the new windows

Ironically, the Lee-Jackson windows were loaned to the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of African American History and Culture and displayed with a temporary exhibit that examined the legacy of Reconstruction and the Lost Cause narrative.

In 2021, the Cathedral announced that Kerry James Marshall had agreed to create racial-justice themed stained-class windows. In September of this year, the new “Now and Forever Windows” were installed in the cathedral.

Marshall worked with second-generation cathedral artisan Andrew Goldkuhle to fabricate the windows. (Goldkuhle’s father created more than 60 of the cathedral’s 231 stained glass windows.)

It is one of Marshall’s three permanent art installations in the country.

The new windows depict a gathering of African American demonstrators holding signs with messages that read “No foul play,” “Fairness,” “Not,” and “No.” The setting intends to depict the ongoing march towards justice and equality rather than commemorate a particular historical moment, while acknowledging the enduring efforts of Black people in the fight for civil rights across the country.

“[Works of art] can invite us and anybody who sees them to reflect on the propositions they present, and to imagine oneself as a subject and an author of a never-ending story that has yet to be told,” Marshall said of the windows. “This is what I tried to do, with words, images and colored glass, for right here and right now.”

Hear more Tennessee Voices: Get the weekly opinion newsletter for insightful and thought provoking columns.

‘American Song’ by poet Elizabeth Alexander will soon be featured too

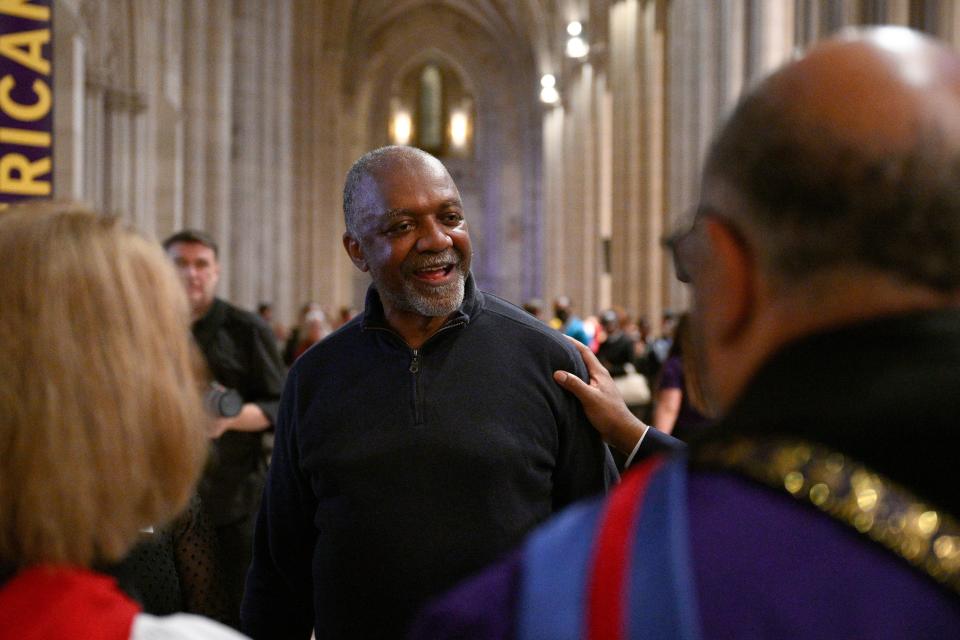

Marshall is an acclaimed artist and art professor who taught painting at the School of Art and Design at the University of Illinois at Chicago. Marshall was featured in the 2017 Time Magazine’s “Time 100” list of the most influential people in the world.

In 1997, he was awarded the MacArthur Fellowship. Born in Birmingham, Ala., Marshall spent his childhood in South Central Los Angeles. Through high school, he studied under the mentorship of the renowned social realist painter Charles White. Marshall earned a Bachelor of Fine Arts degree at Otis College of Art and Design in Los Angeles and has spent much of his career in Chicago.

Sign up for Black Tennessee Voices newsletter:Read compelling columns by Black writers from across Tennessee.

Over the coming months, an additional work will complement Marshall’s stained-glass windows at the cathedral. Elizabeth Alexander’s poem “American Song,” written for this project, will be hand-engraved onto stone tablets in the bay.

“I want to be clear that this is not the end of the Cathedral’s journey,” Hollerith said at the recent dedication of the “Now and Forever Windows.” “Rather, today is an opportunity to recommit ourselves, and to recommit this Cathedral, to join that march towards fairness for all Americans, but especially for African Americans.

“There is a lot of work yet to be done to confront systemic racism, to foster racial reconciliation and to be repairers of the breach, both in the past, the present and in our future.”

Yes, there is much more work to be done to ease the pain and repair the damage of racism. If only more institutions and people in general would follow the example set by the Washington National Cathedral.

Lynn Norment, a columnist for The Commercial Appeal, is a former editor for Ebony Magazine.

This article originally appeared on Nashville Tennessean: Confederate symbols: Washington National Cathedral sets an example