It wasn’t just the Hatfields & McCoys. Why was 1800s Kentucky full of ‘feud’ violence?

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

On Election Day 1882 in Pike County, after a good bit of drinking, which typically accompanied voting at the time in mountainous Eastern Kentucky, brothers Tolbert, Pharmer and Randolph McCoy attacked Ellison Hatfield, who was from West Virginia, across the Tug Fork of the Big Sandy River.

The McCoy brothers cut Hatfield with knives and one shot him, injuring him so badly he later died.

Authorities took the McCoys into custody. But on the way to the jail in Pikeville, Hatfield’s brother, William “Devil Anse” Hatfield, and a group of men caught up with them and took the McCoys.

The posse ultimately tied the three to a pawpaw tree and riddled them with bullets. The youngest, just 15 years old, had his head nearly blown off.

The savagery was part of what became known as the Hatfield-McCoy feud, an example of conflicts in Eastern Kentucky in the decades after the Civil War in which an unknown number of people were killed.

Some of the violence didn’t fit one common definition of “feud” — that is, “a lasting state of hostilities between families or clans marked by violent attacks for revenge,” historians Lowell H. Harrison and James C. Klotter wrote in their book A New History of Kentucky, published in 1997.

The word feud was “carelessly applied” to actions in Eastern Kentucky that didn’t differ much from violence elsewhere at the time, Harrison and Klotter said.

Still, it’s true that there was a large number of shocking killings in Appalachian Kentucky from the end of the Civil War lasting into the early 1900s in some places.

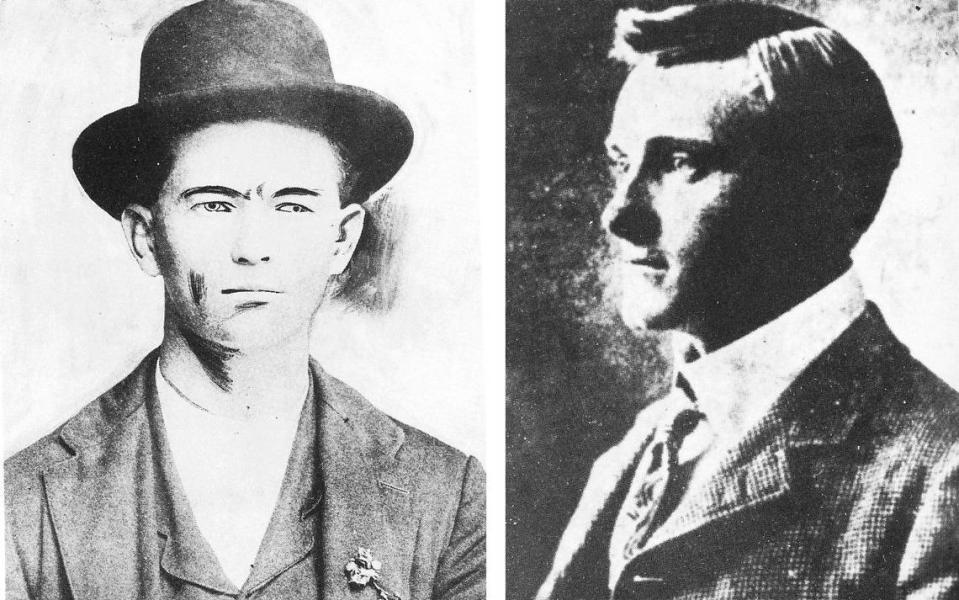

The Hatfield-McCoy feud, with an estimated 12 to 20 people killed, became the most notorious in the national mind because of publicity it received, but it wasn’t the worst.

BREATHITT COUNTY

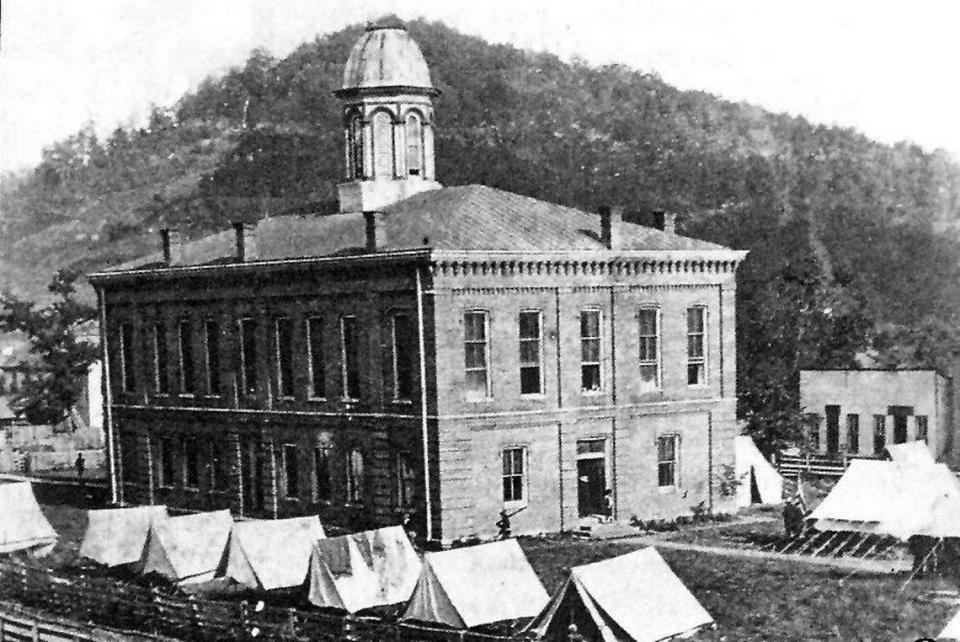

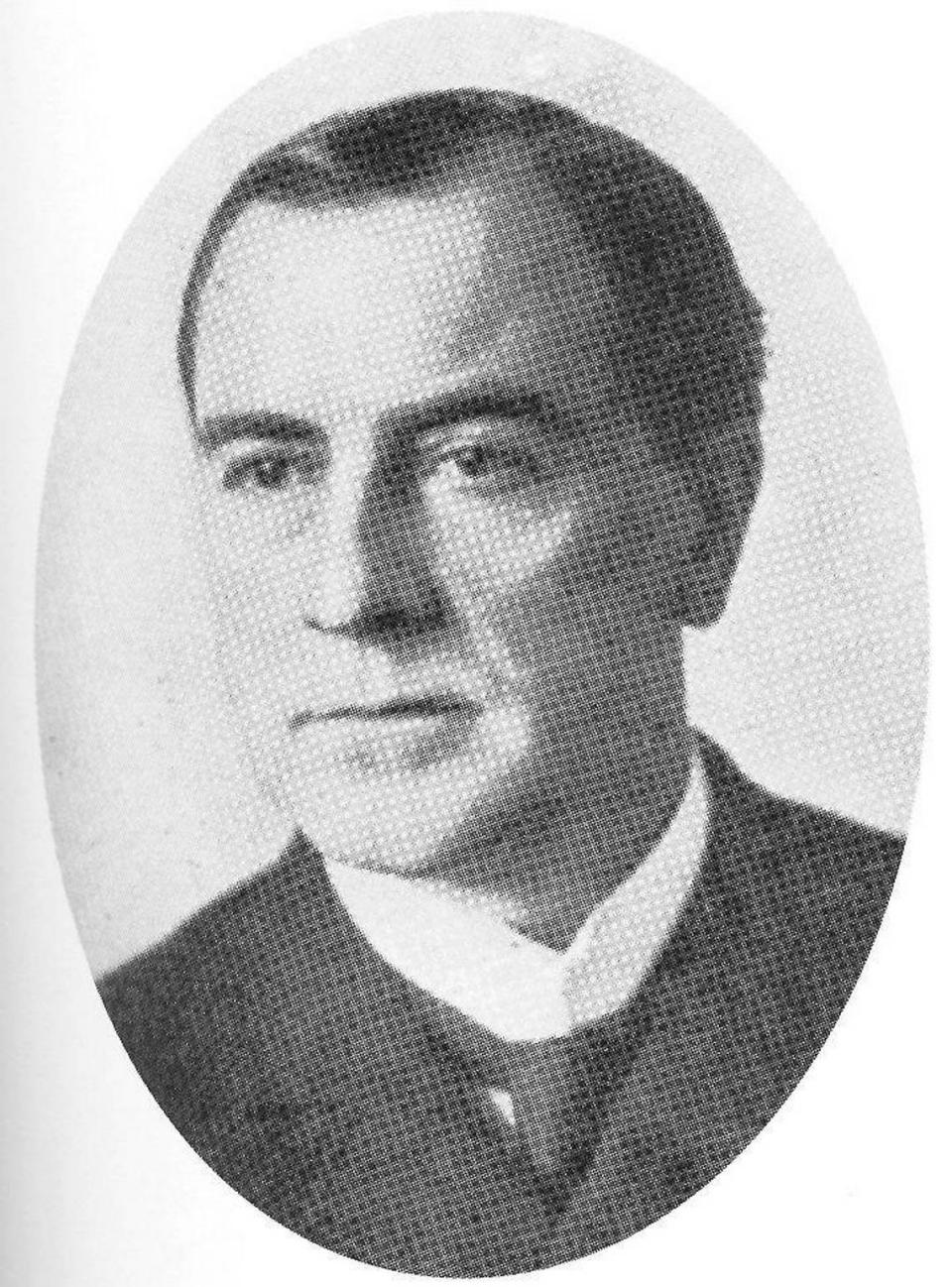

One early-summer day in 1903, attorney J.B. Marcum went to the courthouse in Breathitt County to file some papers.

Marcum — a trustee of what would eventually become the University of Kentucky — had been at odds with another local faction over a recent election, and had said in a letter to a Lexington newspaper that more than 30 men had been killed in the hostilities.

For weeks, Marcum reportedly took a child with him when he left home, apparently thinking his enemies wouldn’t take a shot at him and risk hitting the child.

He went alone to the courthouse in Jackson that day, however, and as he stopped to talk to a friend at the front doorway, someone in the hallway shot him from behind, longtime Kentucky newspaper columnist John Ed Pearce recounted in his 1994 book Days of Darkness: The Feuds of Eastern Kentucky.

“Oh Lordy,” Marcum gasped. “I’m shot. They’ve killed me.”

A witness said he saw the gunman, a deputy sheriff named Curtis Jett, raise a pistol and shoot Marcum again, in the head, before fleeing.

County Judge James Hargis and Sheriff Ed Callahan, opponents of Marcum, reportedly were sitting in rocking chairs at a store across the street and had a view of the courthouse door, but did nothing.

Marcum’s death in what some called the Hargis-Marcum-Cockrell-Callahan feud came at the end of decades of killings in other disputes dating back to soon after the Civil War.

There were estimates that 27 to 38 people had been killed in 1902 and 1903 alone.

ROWAN COUNTY

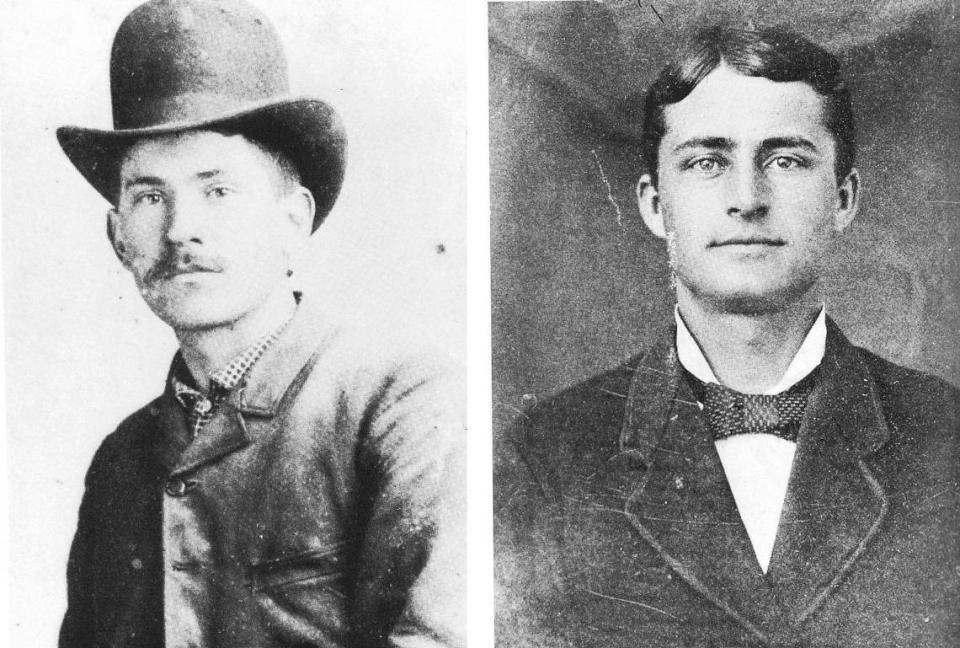

What became known as the Rowan County War, or the Martin-Tolliver-Logan feud, blew up after an Election Day dispute in 1884 that left one man dead and two others wounded.

The county was closely divided between Democrats and Republicans at the time, and for years, “not an election occurred without violent brawls, fraud, vote-buying and loathsome assassinations,” Steven A. Channing, a historian at the University of Kentucky, said in his 1977 book Kentucky: A History.

Sometime after the Election Day killing in 1884, one of the men who had survived, John Martin, ran into “Big Floyd” Tolliver at a saloon and accused him of the earlier shooting, and shot him dead.

A few days later, Tolliver’s brother, Craig Tolliver, used a forged court order to get Martin sent home from jail in an adjoining county. When the train reached Farmers, in Rowan County, several in the Tolliver faction boarded and shot Martin to death.

Ultimately, Craig Tolliver virtually took control of Morehead, prompting attorney Daniel Boone Logan, who had had family members killed, to ask Gov. J. Proctor Knott for help.

When Knott refused, Logan bought enough guns and ammunition to equip a group estimated at 120 to 200 men and surrounded Morehead one morning in June 1887, flushing Tolliver and allies from a hotel and other buildings.

Tolliver was shot and killed as he ran toward the railroad station, and some of his allies were killed as well.

The showdown essentially ended the war.

A state committee later found that there had been 20 men killed and another 16 wounded in the three years before the final showdown, in a county with just 1,100 adult men, Channing said.

The legislature did not approve the committee’s recommendation to disband the county.

PERRY COUNTY

The French-Eversole feud in Perry County in the late 1880s happened against the backdrop of out-of-state businesses to buy up land or rights to the rich seams of coal in the area, Pearce said in his book.

B. Fulton French, a local attorney and businessman, acted as an agent for an outside buyer.

French was a “hard, grasping” man who got a reputation for caring more about getting a good deal for outsiders than local landowners, and another local attorney, Joseph Eversole, reportedly opposed French in an effort to protect small landowners, according to Pearce’s book.

In September 1887, Eversole killed a French ally who had accosted him on the street in Hazard, and a few months later, people fired on Eversole from ambush as he and two other men rode their horses outside town, killing Eversole and one of the men.

The third man, Judge Josiah Combs, who was able to escape, said that as he rode away he saw two men run out of the woods, fire shots into the two men on the ground and then go through their pockets.

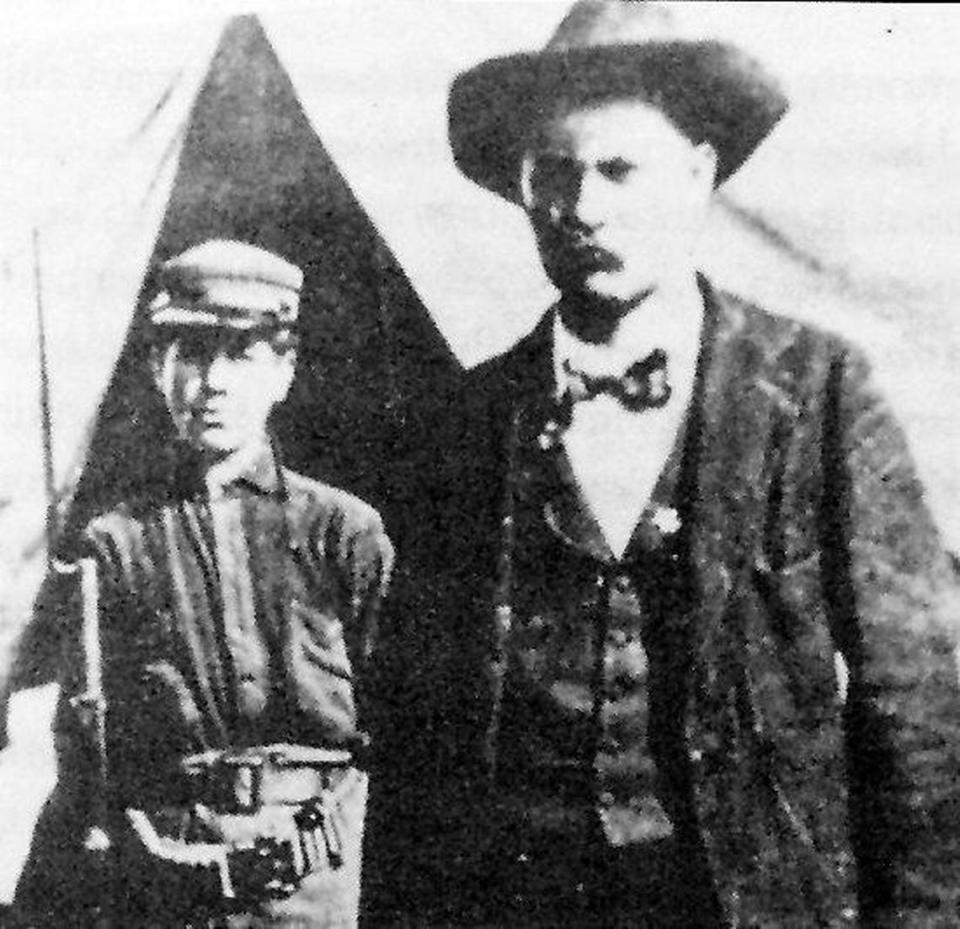

Later in 1888, after the governor sent in troops to guard court proceedings, the leader of the detachment said in a report that more than 20 men had been killed in feuding.

The final major confrontation of the conflict happened when one faction took up positions in the jail and the other occupied the courthouse, shooting at each other until one side ran low on ammunition. Several men were killed or wounded.

HARLAN COUNTY

As with many of the conflicts called feuds, the origins of trouble between the Howards and Turners in Harlan County were murky.

Pearce said in his book that one early confrontation happened when Wix Howard and Little Bob Turner, who had each accused the other of cheating in a poker game, met later on the street and Turner shot Howard in the arm.

Howard blew a hole in Turner’s chest, killing him.

Harrison and Klotter didn’t recount that incident in their history, but said by June 1889 hostilities had reached the point that there was an open battle at the courthouse, with one faction inside and the other attacking from outside.

There was an estimate that 50 people had died in the fighting stretching back decades, the historians said.

CLAY COUNTY

The Garrard-White feud in Clay County has been traced to an 1844 killing by a deranged doctor resulting in a criminal case that pitted the Garrards and Whites against each other. The prominent families were involved in the local salt-production trade and competitors in politics.

From there hostilities flared off and on for decades for various reasons, including revenge. The hostilities involved other families as well, notably the Bakers and Howards.

In one period of a few weeks in 1898, relatives of the county tax assessor, James Howard, were shot and killed from ambush; Howard then shot and killed the county attorney, George “Baldy George” Baker; and a deputy sheriff named Will White was shot and killed, reputedly by Tom Baker, according to book by local historian Charles House called Heroes and Scalawags: The People Who Created Clay County, Kentucky.

One of the signature events in the long-running violence happened in the summer of 1899, as Tom Baker was set to stand trial for the murder of the deputy.

Tensions were high in Manchester and the governor had sent state troops to protect Baker, but it didn’t work.

As he stood outside the courthouse after a hearing, with troops nearby, someone shot Baker from the home of Sheriff Bev White, brother of the slain deputy, which was across the street from the courthouse.

Baker fell dead at his wife’s feet.

White swore he didn’t do the shooting, and no one was ever charged.

‘UNRECLAIMED SAVAGES’

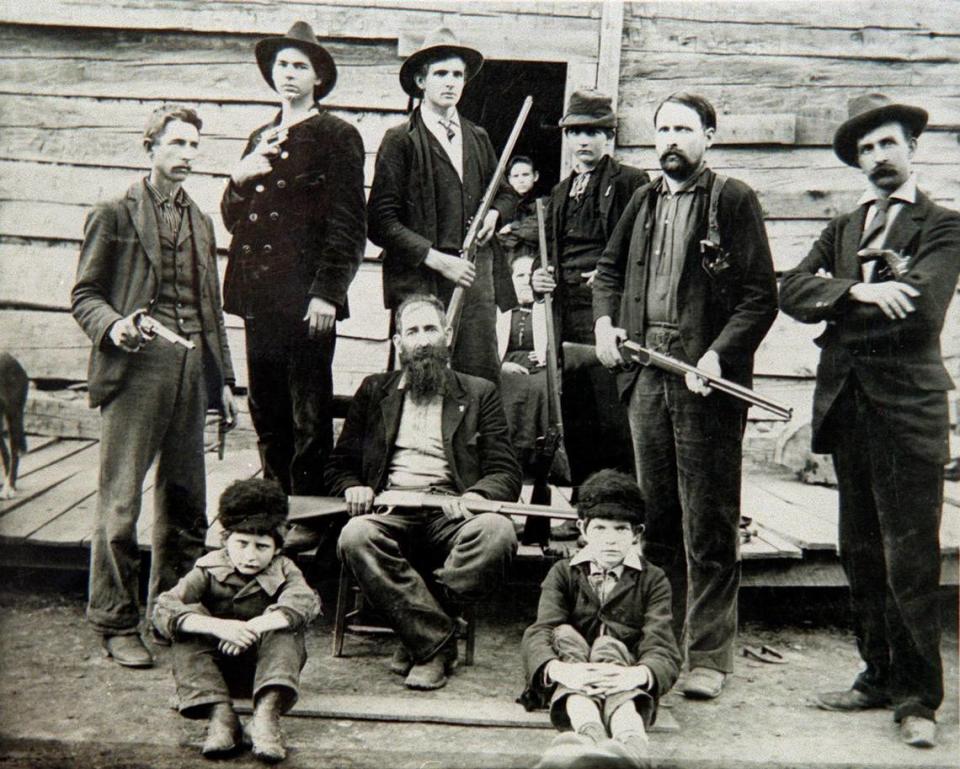

The violence in Eastern Kentucky provided fodder for sensational, often inaccurate, newspaper and magazine accounts that titillated readers across the country and gave rise to the stereotype of the “bearded, one-gallus, barefoot mountaineer sucking his corncob pipe, his jug of moonshine on his shoulder and his trusty rifle ready to deal death to his neighbors,” Pearce wrote.

In reality, leaders of warring factions in many cases were educated, leading citizens of their communities, including lawyers, judges and successful businessmen — though they often used surrogates to do the killing — and economic competition and political rivalry often figured in the bloodletting.

“The violence really was perpetuated by elites,” said retired University of Kentucky professor Dwight Billings, whose book with Katherine Blee, The Road to Poverty: The Making of Wealth and Hardship in Appalachia, examined the development of chronic poverty in Clay County.

Many residents of Eastern Kentucky abhorred the violence, but the entire region got tarred with the same brush, and the stereotype of violence expanded to include the whole state, Harrison and Klotter said, hurting development for decades.

At different times in the 1870s and 1880s, the New York Times called Kentucky residents “unreclaimed savages” and said the state would be a great place to live “if one enjoys anarchy and mobocracy.”

Reasons given for the feuds in popular accounts in the late 1800s were often wrong.

For example, writers sometimes attributed the homicides to some code of honor in the hills, the touchy pride of fiercely independent people, but in truth there was no romance.

It was not unusual for killers to bushwack victims from ambush, and there was certainly no honor in setting fire to a building and killing people as they fled.

‘WOUNDS DON’T HEAL’

More modern scholarship has pointed to other causes of the feuds.

Bob Hutton, a professor at Glenville State University and author of an award-winning 2013 study of the violence in Breathitt County amd the region called Bloody Breathitt: Politics and Violence in the Appalachian South, said he believed much of the violence had its roots in the Civil War.

There were some large battles in the state during the war, but also a good deal of what was essentially guerilla warfare.

Many Eastern Kentucky counties had relatively small populations. People were more likely to be personally acquainted with people on the opposing side, Hutton said.

“When you have guerilla warfare . . . people who know each other hurting each other, those wounds don’t heal overnight,” Hutton said.

Hutton said the bloodshed is more correctly understood as an outgrowth of the struggle going on elsewhere for political legitimacy and dominance out of the ashes of the Civil War, which caused deep divisions in Kentucky, a border state with loyalties on both sides.

Democrats gradually came to control much of Kentucky, but the GOP remained relatively stronger in many counties in Eastern and Southern Kentucky.

Economic and social changes in the years after the war also help explain the bloodletting.

Altina Waller, author of a definitive 1988 book on the most famous feud in Appalachian Kentucky, called Feud: Hatfields, McCoys, and Social Change in Appalachia, 1860-1900, pointed in a 2012 essay to the economic underpinnings of the conflict, which came at a time when the available farm land was being squeezed by a growing population.

Devil Anse Hatfield had been relatively successful in the timber business, while the patriarch of the McCoys, Randal, hadn’t.

“The inability of Randal to provide this kind of opportunity to his sons helps explain their drunken attack on the unarmed Ellison Hatfield,” Waller wrote. “The economic crisis and declining opportunity in the Tug Valley and Appalachia created a situation ripe for resentment, aggression, and violence.”

Several historians have pointed to weak or biased local justice systems, in which factions used courts to protect allies or punish enemies, as a factor in the feuds.

“When no responses or legal redress could be obtained from a legal system ‘rotten to the core,’ other answers would be sought,” Harrison and Klotter wrote.

Channing noted that a state report on the violence in Rowan County said no one had been convicted in 36 shootings in the years leading up to Craig Tolliver’s death.

The report indicated that “grand juries operated chiefly to persecute factional enemies, while criminal trials were frauds, for jurors were either openly approving of defendants or afraid of reprisals by the accused and his friends,” Channing wrote.

Other common elements in the violence cited by Klotter and Harrison included heavy drinking during elections, widespread carrying of concealed guns, and “an intense localism” fed by the relative isolation in the region at the time, when rail access was scarce in many places and roads were poor or nonexistent.

“Take intense kinship feelings strengthened by isolation and intermarriage, mix with partisan hatreds, vivid memories of wartime injustices, weak systems of public education, and a heritage of vigilantism — and the results are not difficult to imagine,” Channing wrote.

Most of the conflicts labeled feuds died out by the early 1900s for various reasons, including one party or faction gaining the upper hand and economic changes that created new conditions.

Hutton said he finds some significance in the fact that the violence in southeastern Kentucky waned “commensurate with the dying-off of the Civil War generation.”

“You eventually run out of people you want to kill for the sake of power,” he said.