'Waste of federal money': Arizona is losing thousands of affordable rentals. Here's how

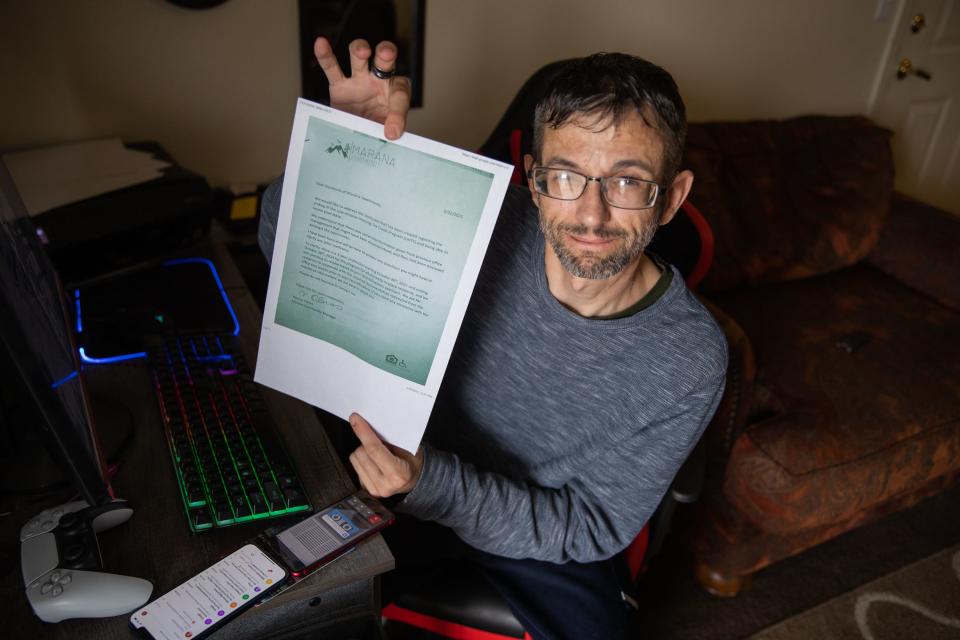

Jason Edwards planned to call Marana Apartments home for many more years.

In 2018, the single father moved into a modest three-bedroom unit there with his two children, Zoey and Dwight, and their dog, Buddy.

The two-story complex of roughly 80 units, which sits off Interstate 10 in the town of Marana about 20 miles northwest of Tucson, is right down the street from his children's schools, a public pool and a dog park.

Rents were affordable, too. The complex was subsidized low-income housing, and Edwards, who describes himself as partially disabled, was told it would stay that way for years to come.

But a provision in federal law has upended Edwards' plans. His family will likely be pushed out of the complex next year, when a new corporate owner is allowed to raise his rent.

"It's appalling that they're doing this to people," Edwards said.

Like all housing built under the federal Low-Income Housing Tax Credit program, Marana Apartments was meant to remain affordable for at least 30 years. While most LIHTC complexes meet that requirement, federal law allows some properties subsidized by the tax credit program to be converted to market-rate housing in half that time.

In Arizona, this has meant the premature loss of thousands of affordable housing units.

As the country grapples with an affordable housing crisis, the "qualified contract" provision, which allows properties to exit the LIHTC program early, is quietly draining Arizona and other states of what was supposed to be long-term, government-subsidized affordable housing. Many affordable housing advocates say the provision is being used in unintended ways and has become a loophole for LIHTC property owners to exploit.

The Arizona Republic spent five months investigating the qualified contract provision by analyzing government data and apartment records and interviewing more than 50 people, including affordable housing experts, property owners and residents living in affected properties in the Phoenix, Tucson and Yuma areas. The reporting found:

Since 2010, 70 Arizona properties have gone through the qualified contract process, costing the state more than 5,700 LIHTC housing units, according to Arizona Department of Housing records.

The Arizona Department of Housing implemented a policy in 2010 that makes it nearly impossible to use the qualified contract provision for properties that received the tax credits that year or later. But it doesn't apply to properties that sought low-income housing tax credits before 2010, meaning the state could potentially lose up to 10,000 more LIHTC units in the next several years.

Many of the property owners using the qualified contract process are investors that profit from raising rents at the expense of low-income tenants. Apartment owners are not required by law to tell tenants when a property is going through the process and will likely be converted to market rate, leaving some residents unaware that they could soon be pushed out.

Some property owners that use the qualified contract process are affordable housing nonprofits that say they would have liked to keep the properties affordable but simply couldn't afford the upkeep of the aging buildings.

Nationwide, more than 100,000 affordable units have likely been lost via the qualified contract process since 1990, according to National Low Income Housing Coalition estimates. Multiple attempts by federal lawmakers in recent years to repeal the qualified contract provision have failed.

Most of the more than 600 properties financed with low-income housing tax credits in Arizona have not gone through the qualified contract process. Yet affordable housing experts and advocates say the process undermines the LIHTC program, which the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development calls "the most important resource for creating affordable housing in the United States today."

While the qualified contract process is perfectly legal, losing thousands of affordable units because of it is a “waste of federal money,” said Robert Rozen, a national affordable housing expert and policy consultant who was the lead U.S. Senate staffer working on the LIHTC program when the qualified contract provision was created in 1989.

“It’s an abuse of the program," Rozen said.

Qualified contract process is lucrative business strategy

FSO Capital Partners, a private equity real estate firm based in Phoenix, purchased Marana Apartments for $4 million in July 2020 from the Tucson-based affordable housing nonprofit TMM Family Services Inc. The property began going through the qualified contract process three months later.

A representative of TMM said the organization was unaware that the property had gone through the qualified contract process and was being converted to market-rate rents.

The organization sold the property and two of its other LIHTC properties because it couldn't afford the necessary repairs to maintain them, said Steve Ponzo, chair of TMM's board of directors.

“Look, our mission is to provide low-income housing. ... We don't want to turn a property over where we know someone is going to immediately take it to market rent," Ponzo said. "But also, there's so much money that would have to go into these properties. And, unfortunately, low-income housing doesn’t pay the bills.”

FSO Capital Partners now estimates the property is worth $16.8 million, according to its website. That's more than four times what the company paid for the complex less than three years ago. The company is "focused on identifying and acquiring undervalued assets and driving operational excellence" and owns 14 properties in Arizona, its website said.

Per federal law, residents like Edwards who were already living at the property in October 2020 have until October 2024 before their rents can be increased to market rate.

But for new residents, the rent hikes have already begun. A three-bedroom apartment now rents for roughly $1,600, according to the Marana Apartments website. By comparison, the monthly rent for Edwards’ unit was $889 in 2020.

"Come experience newly renovated apartment homes at Marana," the complex's website said.

Marana Apartments opened in 2003. If it had remained in the LIHTC program for its full 30 years, it would have stayed affordable until at least 2033.

Edwards worries about his neighbors. Many of them work low-wage jobs, are senior citizens or people with disabilities on fixed incomes or, like him, have a federally funded housing voucher. Come 2024, many don’t know where they will go. There are no other LIHTC properties in Marana.

“They’re choosing to make money in one of the most unethical ways,” Edwards said of the property owners. “You’re making money by throwing the most vulnerable people onto the streets.”

FSO Capital Partners did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

How a decades-old policy is making affordable housing disappear

These are the basics of the qualified contract process:

A housing developer receives low-income housing tax credits and, in return, the property is supposed to be kept affordable for 30 years. But after 14 years, the property's owner can apply to exit the program.

The Arizona Department of Housing, which manages the LIHTC program in Arizona, then has a year to find a buyer that will keep the property affordable. It's a nearly impossible task. The sale price of the property is calculated using a formula in the federal tax code that prices many properties higher than their fair market values. Of the 70 properties that have gone through the qualified contract process in Arizona since 2010, the state did not find a buyer for any of them.

If no buyer is found, the property is released from the LIHTC program. The property owner must keep rents affordable for existing tenants for three more years but can start charging new residents higher rents immediately.

After three years, the entire property can be converted to market rate as long as there are no other affordability requirements tied to the property.

The qualified contract provision was put in place when the LIHTC program was revamped from a 15-year program to a 30-year program. There was concern that it could be hard to get investors to put up capital to build developments with the longer affordability requirement.

For more than 20 years, no one paid much attention to the provision. A 2012 HUD study found that only a small share of property owners exited the LIHTC program via the qualified contract provision.

But that has changed in recent years. Given the red-hot real estate market, the gap between affordable and market-rate rents has widened, and some LIHTC property owners have realized they can capitalize on it.

“Investors are sort of sharing this strategy with each other to help facilitate more and more investors to get out of the program early," said Sarah Saadian, senior vice president of public policy and field organizing at the National Low Income Housing Coalition, which advocates for eliminating the qualified contract provision. "Because they see it as a good way of making money, right?”

In less than three years, Marana Apartments and six other properties that FSO Capital Partners or one of its principals, Jeffrey Sherman, owns or manages — totaling about 450 units of affordable housing in Marana, Yuma, Thatcher and Wickenburg — have gone through the qualified contract process, according to property records and data from the Arizona Department of Housing.

In Arizona, more than a dozen other entities or individuals are taking advantage of the increased cash flow the qualified contract process can deliver. Several other investment firms, individual investors, affordable housing developers and nonprofit organizations — including some from out of state — own multiple properties that are currently going through the qualified contract process, property records and documents from the Arizona Department of Housing show.

At the end of 2021, Edwards started noticing changes around Marana Apartments. Workers gave the building a fresh coat of paint and repaved the parking lot. A notice from management about renovations mentioned lease renewals "at market rate," confusing some residents and sending them into a panic, multiple residents said.

The property manager gave Edwards incomplete and, at times, inaccurate information about the property's conversion to market rate, at one point telling him that all of the apartments would likely have to be remodeled and rents would increase in 2023, according to a recording of the conversation. Edwards began packing his family's belongings in boxes, preparing to move out.

Desperate for answers, Edwards contacted the town of Marana in March 2022. A town official told him what was happening. “After October 30, 2024, all of the rents can be charged at a market rate,” wrote Lisa Shafer, community and neighborhood services director, in an email.

Edwards also contacted the Arizona Department of Housing, which urged FSO Capital Partners to inform residents of their rights, emails show.

"To clarify, there is a 3-year protection ... for all currently in-place residents," the property manager wrote in a letter posted on residents' doors the following day.

Multiple residents said the letter was the first clarification they received about the situation. Many said they were relieved they still have some time before their rents dramatically increase but are stressed about finding somewhere else affordable to live before October 2024.

“Right now, I have no backup plans," said Jaymie Conrad, who works as a hairdresser and has lived in Marana Apartments with her daughter for almost a decade. "I’m just hoping and praying that between now and then I'll find something, or something will change — I don't know.”

Vince Reterstorf, who has lived in the complex for three years and frequents the senior center down the street, also will soon have to leave. The 76-year-old's retirement and Social Security benefits won't be enough to pay for the rent hike, he said.

“I’ve got to move out of here, and I have nowhere to go,” Reterstorf said.

Despite congressional efforts, the qualified contract provision lives on

Lawmakers and affordable housing advocates have for the past five years been pushing for the qualified contract provision to be abolished. So far, their efforts have been unsuccessful.

Members of Congress, primarily Democrats, have three times pushed legislation that would eliminate the provision for new LIHTC properties and adjust the qualified contract sale price to market rate for existing properties, which would likely discourage owners from going through the process.

The Save Affordable Housing Act of 2019 and the Decent, Affordable, Safe Housing for All Act of 2021 both stalled in committee. Language that would have repealed the provision was included in an early version of the Build Back Better Act but ultimately was removed.

The Decent, Affordable, Safe Housing for All Act was reintroduced in March.

"It really is an issue that requires a federal fix," said Jennifer Schwartz, director of tax and housing advocacy at the National Council of State Housing Agencies, which represents state housing finance authorities.

Arizona has taken steps to mitigate the issue. Most notably, in 2010, the Arizona Department of Housing began incentivizing applicants for the most substantial low-income housing tax credits to waive their right to the qualified contract process by awarding them extra points on their applications. Because that tax credit program is so competitive, the move has made it virtually impossible to receive the credits otherwise.

Developers of every Arizona property subsidized by the most valuable low-income housing tax credits since 2010 have waived their right to the qualified contract process, meaning those properties must stay affordable for the full 30 years.

But more than 150 properties received tax credits before 2010 and still have the ability to go through the qualified contract process, according to data from the state housing department. If they do, Arizona could lose thousands more affordable units.

“They’re not doing anything illegal, FSO or anybody who goes through this process,” Rozen said. “But they’re making a lot of money at the expense of low-income people.”

Send us your tips

The Arizona Republic is continuing to report on the qualified contract process. If you or someone you know has lived in a property that has gone through the qualified contract process, or if you have any other information to share, we want to hear from you.

Email reporter Juliette Rihl at jrihl@arizonarepublic.com. Send letters and documents to Juliette Rihl, The Arizona Republic, 200 E. Van Buren St., Phoenix, AZ 85004.

Juliette Rihl covers housing insecurity and homelessness for The Arizona Republic. She can be reached at jrihl@arizonarepublic.com or on Twitter @julietterihl.

Coverage of housing insecurity on azcentral.com and in The Arizona Republic is supported by a grant from the Arizona Community Foundation.

Arizona Republic reporters Catherine Reagor, Diannie Chavez and Kunle Falayi contributed reporting.

This article originally appeared on Arizona Republic: Qualified contract process leads Arizona to lose low-income rentals