Most babies with this rare genetic disease are on ventilators by 8 months. This Austin baby beat the odds

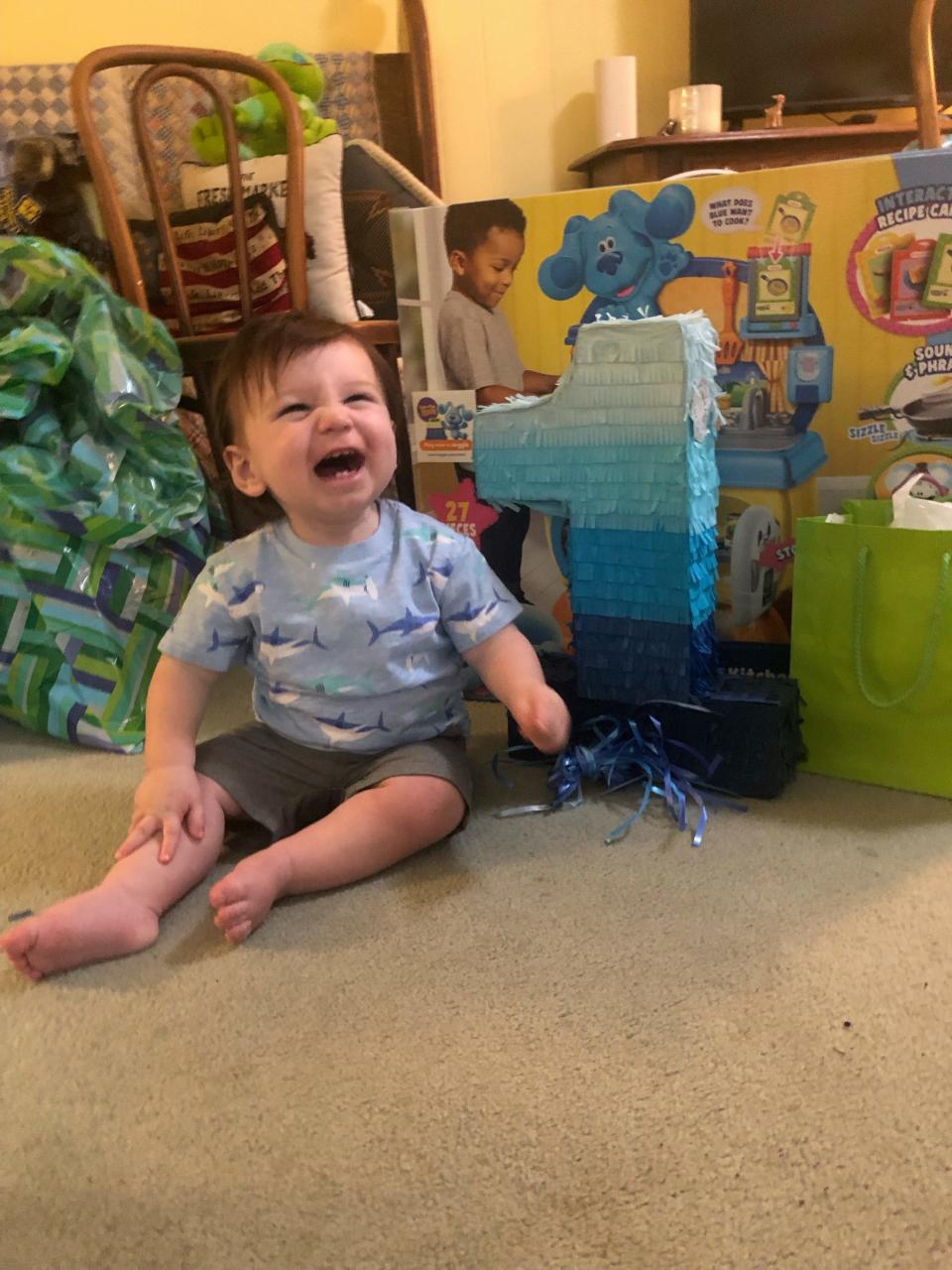

Noah Strauch loves to laugh. He loves to put things into a bucket and dump them out again. He crawls so fast, his parents have difficulty keeping up with him. And he loves strawberries and chocolate milk.

The 15-month-old most likely would not be crawling or dumping things into and out of a bucket if the newborn screening program in Texas had not added spinal muscular atrophy to the blood tests infants get at 1 day old and again at 2 weeks old. The screening program was added just 88 days before he was born.

Noah was the first baby in Texas to be identified with spinal muscular atrophy — commonly known as SMA — through the newborn screening. A month to the day after his birth, he received gene therapy that is expected to prevent him from suffering the effects of the disease throughout his life.

"He's just something else," said his mom, Mikayla Strauch. "I'll just hear him talking and playing. I love watching him grow."

More on SMA:Twin 'was just melting': Babies with neuromuscular disease find new hope in Austin

Understanding SMA

SMA is caused by a genetic mutation. Both parents have to be carriers of the mutated gene for it to occur. There is about a 25% chance for such a couple's baby to have SMA.

People with SMA do not make the survival motor neuron protein because they do not have the SMN 1 gene or the gene is mutated. That protein is needed to protect motor neurons, which control the body's ability to move muscles. People with SMA do have the SMN 2 gene, which also can make this protein, but the gene cannot make enough of the protein to cover all the motor neurons, and the neurons begin to die.

SMA comes in various levels, from 0 to 4. SMA 0 babies sometimes die before birth, or if they are born, they immediately have trouble breathing. With each increase in number, the later the symptoms become noticeable and the greater the chance of living longer without intervention, in general.

SMA 1 is the most common form and is what Noah has. Babies with SMA 1 typically are on a ventilator by 8 to 9 months, said Dr. Vettaikorumakankav Vedanarayanan, a pediatric neurologist at Dell Children's Medical Center of Central Texas who treats children with SMA. SMA 1 babies typically don't live beyond 2 years.

A difference with screening

Before newborns were screened for SMA, most SMA 1 babies were diagnosed between 3 and 6 months, when they start missing their milestones because their muscle condition begins to worsen.

With Noah, when the hospital did that first heel prick, the Strauch family was told to see a pediatrician immediately. The second heel prick, done within days, confirmed the diagnosis.

Those newborn screening heel pricks allow for testing for SMA, 33 other primary conditions and 21 secondary conditions. Newborns in Texas also get a congenital heart condition screening and a hearing check.

"He wasn't even a week old when we found out," Mikayla Strauch said.

Noah looked perfectly healthy, and the Strauches had no family history that would have told them they were both carriers of the genetic mutation.

Within 24 hours of the official diagnosis, they had met with Vedanarayanan and his team, including a social worker. They were given three options for treatment: a gene therapy given intravenously that Noah would need to have only once in his life, an intravenous solution he'd need every four months until it could be given as an oral medicine at age 2, or another oral medication he would take every day.

The Strauches chose the gene therapy, Zolgensma.

They knew if it didn't work, they would have more options later, but Zolgensma is designed to be given before a child turns 2, and the sooner it is given, the less the effects of SMA will be felt.

Future of rare diseases:'We're getting there': Austin's Dell Children's hospital keeps taking steps toward its lofty goals

Getting gene therapy

On Sept. 27, 2021, Noah stayed at Dell Children's Medical Center for 48 hours — an hour to be given Zolgensma intravenously and the rest of the time to make sure he didn't have any adverse effects.

Zolgensma was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in 2019 for children under 2 years old. It uses a virus to carry a new copy of the SMN 1 gene. The virus infects the cells with the new DNA that has the SMN 1 gene.

Doctors can tell whether it's working because they can later find SMN 1 cells in places such as the central nervous system and the muscles.

"In general, what we find is it's better to do it as quickly as possible," Vedanarayanan said. "When they are smaller in size, we have to give a smaller amount of virus load, and there's a lower amount of immune response."

If the treatment comes when infants are older, the SMA effects might already have been felt, and "we have to deal with the immune response," he said. That means giving steroids along with the Zolgensma and looking out for liver and heart damage because of the steroids.

Because a virus carries the gene therapy, the Strauches had to do things such as wear gloves when they changed Noah's diapers to keep from being infected.

If they wanted to have more children, they didn't want to build up antibodies that would fight the virus. If they did, Zolgensma could still be given, but they would have to wait until that baby no longer had the mother's antibodies, usually around 3 to 5 months old. Until Zolgensma could be given, they would use injections of another therapy to stave off SMA effects.

Right now, Zolgensma is only for children younger than 2 years old, but trials are being done for children who are 5 to 6 years old to see if it will work in older children.

Saving more babies: 'A 50-50 shot': How a Dell Children's team used a risky heart surgery to save a tiny infant

Treatments key to screenings

Until six years ago, people with SMA didn't have any treatments approved by the FDA.

The first drug approved was Spinraza in 2016 for all types of SMA and all ages. It's an injection in the spinal fluid given twice at first and then every four months for the rest of the person's life. Spinraza helps increase the production of the SMN protein by the SMN 2 gene.

Zolgensma was approved in 2019.

A third medication for SMA was approved in 2020. Evrysdi is an oral medication taken every day for ages 2 months to adulthood. Like Spinraza, Evrysdi does nothing about the SMN 1 gene. Instead, it tries to boost the SMN 2 gene to make more of the SMN protein.

Before these therapies existed, a newborn screening for SMA was highly unlikely. The Texas newborn screening program takes its cues from the federal Advisory Committee on Heritable Disorders in Newborns and Children.

The general practice of that committee, which hears proposals on what diseases should be added to the Recommended Uniform Screening Panel, is to screen only for conditions that have a treatment that will make a measurable difference when given early.

That committee talked about SMA in 2008 but did not move forward because there weren't any therapies available other than physical therapy and nutritional support.

Once there was Spinraza, the federal committee could move forward and recommend that SMA be added to the Recommended Uniform Screening Panel by approval of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services secretary. That happened in 2018.

Getting the mutation added to the Recommended Uniform Screening Panel was just the first step to Texas newborns being screened. Each state decides which items it wants to add to its newborn screenings.

It takes about three or 3½ years to make it onto Texas' newborn screening list if the state decides to add it, said Debra Freedenberg, medical director of the newborn screening unit and genetics at the Texas Department of State Health Services.

It's not a simple process. The state has to develop the testing protocol, train the laboratory technicians and calibrate testing machines. Each condition can require different lab equipment, reagents and supplies.

The state also has to develop a communication plan about the new test and assemble resources for families and pediatricians.

The state also has to find funding for the condition to be added to the newborn screening panel. To add SMA, the fee for a newborn screening rose $2.97, from $60.58 to $63.55 per infant. That gets paid by private insurance, Medicaid or a charity program.

"We do wish it was quicker," Freedenberg said of the three years or more it takes from when a screening is added to the federal panel to when it starts in Texas. "We can't blink twice and snap our fingers and have everything involved in place."

For 2024, the state is working on adding two diseases to the newborn screening: Mucopolysaccharidosis type I and Pompe disease. In August, the federal committee added Mucopolysaccharidosis type II, which paves the way for the state to consider it. The federal committee is waiting on the U.S. Health and Human Services secretary to sign off on adding Guanidinoacetate methyltransferase (GAMT) deficiency to the recommended screenings.

Looking to the future

More therapies for SMA are on the way, including an agent to build muscles or muscle mass. Researchers are also looking at delivering gene therapy in a smaller dose directly into the spinal fluid.

"What I tell trainees and medical students is gene therapy is going to be the next big step," Vedanarayanan said.

He envisions that many things that cannot be treated now will be able to be treated in the future with gene therapy.

What is not known is the long-term outcome of the Zolgensma treatments. The oldest children who received it after it was approved by the FDA are now around 6 years old and entering first grade, "which was unheard of," Vedanarayanan said, before this therapy.

"There are questions. How will they be in their 20s and 30s? Will this gene last?" Vedanarayan said.

Noah continues to be closely monitored by Vedanarayanan. He also receives physical therapy to check his milestones.

"The lack of development is the progression of the disease," Mikayla Strauch said.

So far his physical therapists have not noticed anything out of the ordinary, she said.

"He's a good, healthy baby," she said.

This article originally appeared on Austin American-Statesman: 'Watching him grow': New test saves Austin baby with muscle disease