'Water underground wants to go back': Can ongoing work save Portsmouth history?

PORTSMOUTH, NH — The city's most iconic park and historical homes in the South End are in danger of being destroyed — not by a bulldozer to make way for new construction, but by water deep beneath the ground.

The Strawbery Banke Museum homes, the oldest of which dates to 1695, and Prescott Park sit along the bank of the Piscataqua River. The beloved 10-acre park with its flower gardens and open-air performance space is an oasis in a city facing strong pressure from development.

These historic homes are already dealing with the turbulence of the climate crisis. Centuries-old foundations are cracking not because of age but because of water. Decades of groundwater intrusion are eroding the historic structures.

Filling Puddle Dock was a solution but it is becoming the problem

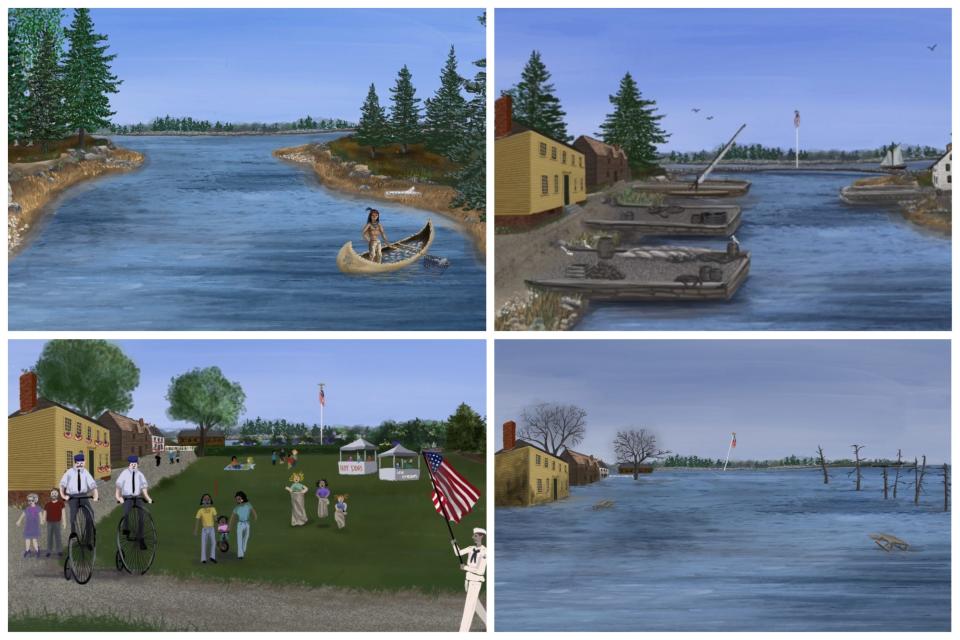

What currently stands as a grassy area of Prescott Park and Strawbery Banke was once a tidal inlet of the Piscataqua River channel.

Before English settlers arrived, the coastal area was a fishing spot for the Abenaki Indigenous people. As English settlers populated the area in the 1620s, they built docks, wharfs and established the Strawbery Banke community built around the inlet, that would later be called Puddle Dock.

The area was a safe harbor for two centuries, deep enough for boats to load and unload goods. As the economy changed over the centuries, Puddle Dock’s purpose waned. By the early 1900s, the inlet was filled in, and it was a decision that would have significant consequences more than a century later.

Washing up history: Boston Tea Party rebels and shipwrecked souls rest here. The ocean had other ideas, though.

Water wants to return to where it naturally flowed

Rodney Rowland stands in the green at the center of the property, resting against a tree. This issue is something he’s worked to solve for decades, most recently as the director of facilities and environmental sustainability at the museum.

Preserving the area’s history became a priority in the 1950s, after city officials planned to demolish the neighborhood for "urban renewal.” A group of local activists, determined to preserve the centuries of history in a collection of original historic houses, formed Strawbery Banke, Inc., in 1958. The property became a museum on a 10-acre site with 30 buildings.

“This whole field is underwater when it floods,” Rowland said, pointing to different areas of the green. “If we do nothing, this entire area, and the homes around it, will be underwater by several feet. If you think the flooding issue is already this bad, just wait. It would be so much worse.”

Rowland has worked at the museum for 31 years.

His parents were involved in the museum’s early days, so he'd been a frequent visitor since he was 10. The effort to save these historic homes from being demolished changed the course of his life. It inspired him to major in history, and he began working for the museum after graduation.

Now he’s on a mission, being the second generation in his family trying to save these homes.

Even though the inlet has been filled, the tide and rising sea level still affects the groundwater in the land beneath the houses, because the area is one of the lowest points in the city.

“Water has a memory,” Rowland said. “When they filled in the inlet, they didn't know the river would get this high. We can’t see it, but the water underground wants to go back to its natural groove. We see the effects on the foundations and flooding issues.”

The level of water in the river has also increased over time and can drastically fluctuate due to impacts and storm surges and sea-level rise, pushing the water even higher.

The city’s stormwater system is underneath the property and drains water into the Piscataqua River. The water has nowhere to go at high tide, when the outflow pipe into the river is underwater.

This poses a threat to most historic buildings of Portsmouth’s South End, many of which are still on their original foundations. It’s not just water damage experts are worried about; it’s the mold, mildew and foundation issues that are caused by the water.

These historic structures from throughout the centuries are already flooded annually.

“Basements flood on a monthly basis, but because we are a historic site and preservation is really key to what we do, we don't want to go putting buildings up on stilts or moving them entirely to higher ground,” Rowland said. “That alters the experience and history. We can’t sacrifice too much of our history.”

An ongoing museum exhibit is called “Water Has a Memory,” inspired by the impacts the filled inlet is having on the property. One of the interactive displays portrays a screen that looks like a window peering out at the greenspace outside. It shows artists' renditions of how this view has changed throughout the centuries, with a rendering of how the neighborhood would be underwater in 100 years if nothing is done.

Not just a beachfront problem: It’s everywhere: Sea-level rise’s surprising reach damaging more than East Coast shoreline

“Few historic neighborhoods like this are original and not homes that were moved to a certain place to teach and preserve history,” Rowland said. “Being threatened by climate change really matters.”

The city of Portsmouth is planning for an expected 1- to 1.7-foot sea level rise by 2050, and a 6-foot rise by 2100, according to a report by federal climate scientists.

People are working to protect Prescott Park

The park is best known for the Prescott Park Arts Festival held every summer since 1974. It started as a summer musical theater production, celebrating the nation’s bicentennial. It grew into an annual tradition, a celebration of arts and culture through music, visual art, and musical theater.

Courtney Perkins, executive director of the Prescott Park Arts Festival, said that it is “truly a grassroots organization born out of a community's love for the arts and culture.”

Today, the festival provides more than 90 diverse arts events to nearly 150,000 people each season.

“Prescott Park represents Portsmouth to me in so many ways — in its history, in its proximity to the water, in its well-established beauty, but also in all of the hidden gems it has to offer if you have the time to look,” Perkins said. “It is a space meant to gather community and that's what we do.”

Tom Watson, who served on the Prescott Park master plan committee, has spent years evaluating what parts of the park were at the most risk.

Protecting what Watson hails as “the city’s greatest gem” will take a lot of work and money.

Building resiliency to protect from the 100-year storm and sea-level rise

The city started a master planning process in 2016 to look at the park because a climate impact report showed just how vulnerable it was to flooding. Those studies showed that if nothing is done, the park could be mostly underwater in the event of a major “100-year” storm surge or future sea-level rise.

Key suggestions for future improvements included:

raising and relocating the former historic Shaw Warehouse

shoring up and raising the aging seawall

improving stormwater management

creating a defined bowl-shaped performance area that can double as a reservoir when it floods

relocating the gardens

“A lot of the plan is moving the pieces of the park around like pieces of a puzzle,” Watson said. “If we are going to preserve the past and ensure the future of these areas, we have to start thinking about building resiliency into our historic structures and protecting the areas we treasure.”

It’s a multi-year plan that will be undertaken in stages that was expected to take up to 10 years once started.

Watson recently urged the Portsmouth City Council that the city cannot wait to move forward with the effort to counteract the effects of climate crisis. With the council’s approval in July, the first phase of improvements in the park’s master plan can begin as early as spring 2023.

The city estimates the initial improvements will cost $2.7 million of the $3.5 million previously set aside for the project.

The work in Phase 1A of the renovations will include:

raising and moving the Shaw Warehouse

installing new stormwater, gas and water utilities under Water Street, which runs through the park

resurfacing and raising Water Street

The new stormwater system will drain excess water and runoff into the Piscataqua River.

“The work we’ve done suggests that the flooding situation is much worse than we anticipated in 2016,” Watson said. “We have to modify the plans to address these concerns or all our work will float away in water caused by significant rain storms and general sea-level increases.”

Can Strawbery Banke stay above the water?

The Henry Sherburne House is the second-oldest house in Portsmouth. The tides have worn the structural integrity of the soil beneath it.

“A lot of people don't understand that they have a groundwater issue in their basements because they don't see water,” Rowland said. “Even if it's just a few inches below the ground, that soil is soaking wet all the time. It doesn’t take much for it to do damage.”

The brick foundation of the chimney shifted and started to take the house with it, Rowland said. The museum plans to possibly fill in the basement as support, and build a smaller chimney.

“Unfortunately, you have to lose some history to save the rest,” Rowland said. “When a brick loses its structure like that, you can literally hold it in your hand and crumble it. If we don’t catch it at the base, that deterioration works its way up the chimney.”

Rowland said that it is working with the city to find a solution for their stormwater issues, and how to shore up the houses so they are protected. He hopes a plan can be in place by the end of the year, so the museum can fundraise.

“The sea-level rise initiative is the most important thing the museum’s ever done because it’s about preserving who we are, what we do, and the stories we tell. It’s our job to make sure that history doesn’t get washed away,” Rowland said.

— This article is part of a USA TODAY Network reporting project called "Perilous Course," a collaborative examination of how people up and down the East Coast are grappling with the climate crisis. Journalists from more than 35 newsrooms from New Hampshire to Florida are speaking with people about real-life impacts, digging into the science and investigating government response, or lack of it.

This article originally appeared on Fosters Daily Democrat: Rising sea-levels threaten Portsmouth's Prescott Park, Strawbery Banke