Watergate scandal wasn't just a burglary, it was a state of mind | Opinion

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

June 17 marked the 50 year anniversary of the botched 1972 burglary at the Democratic National Committee (DNC) office in the Watergate complex in Washington D.C., which was soon linked to President Richard M. Nixon's reelection campaign, then to the White House itself.

The scandal would reveal the dangers of presidential administrations that are dominated by a siege mentality.

The two-year drama that unfolded after the burglary, with its plot twists and cast of colorful, often unsavory characters, ultimately led to the impeachment and resignation of Nixon, who was pardoned a month later by his successor, Gerald R. Ford.

18 other White House aides were not so lucky and served prison time for their actions — notably, for perjury, conspiracy, and obstruction of justice.

Hear from Tennessee's Black voices: Get the weekly newsletter for powerful and critical thinking columns.

Watergate was a state of mind

During the Senate's 1973 investigation of Watergate, Senator Howard Baker of Tennessee, a Nixon ally, famously asked, "What did the President know, and when did he know it?"

We may never have a definitive answer to those questions, but some of his top aides believed the president had ordered the burglary in order to "nail" Lawrence O'Brien, the DNC chairman and Kennedy confidant whose office telephone was wiretapped by the burglars.

However, we might now consider Baker's questions somewhat moot, for as investigations proceeded, Watergate came to stand not only for the DNC break-in and subsequent cover-up, but also for an assortment of other unethical, corrupt, criminal, and unconstitutional actions that were exposed. In this broader sense, 'Watergate' was the dynamic reflection of President Nixon's paranoid state of mind, which made the DNC burglary both thinkable and doable.

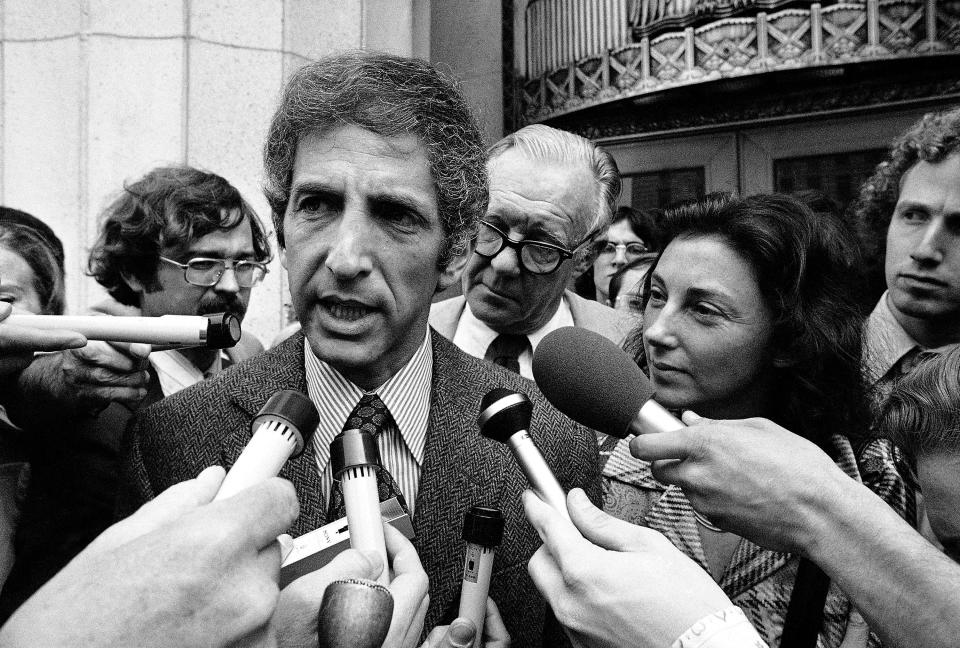

As the White House tapes and other sources attest, Nixon had a penchant for seeing conspiracies where there were none. In June 1971, a whistleblower named Daniel Ellsberg had provided the press with "the Pentagon Papers," purloined copies of a top-secret history of US involvement in Vietnam through 1967. Ellsberg acted on his own, but Nixon thought otherwise. "It's a conspiracy, Bob," he told his chief of staff. "We're going to fight with everything we've got."

Nixon believed that a center-left think tank, the Brookings Institution, had aided Ellsberg and possessed other classified documents, so for the next two months, he repeatedly harassed his staff to get into Brookings, "crack the safe," and retrieve their files.

Nixon's newly-formed internal secret police, known as the Plumbers, strongly considered firebombing the institute as a cover for this burglary, but instead they settled for breaking into the Los Angeles office of Ellsberg's psychiatrist in search of damning information.

It seems unlikely that the same president who was hell-bent on breaking into a think tank's vault would have shied away from bugging his political opponents a year later. A hallmark of what one historian termed "the paranoid style" is viewing one's opponents in the most sinister light, thus rationalizing extraordinary means to combat them.

Hear more Tennessee Voices: Get the weekly opinion newsletter for insightful and thought provoking columns.

Nixon administration didn't have opponents; it had enemies

The President and his aides viewed his Democratic challenger in 1972, Senator George McGovern, as a traitor and a "Communist SOB," justifying what Nixon called an "absolutely ruthless" campaign.

Even after Watergate, he was neither contrite nor more cautious in pursuit of McGovern's destruction. Instead, Nixon complained that his staff was "too addicted to the law" because of the Watergate incident. "We have all this power and we're not using it!" he raged.

Eventually, his arrogant attitude toward the law would lay Nixon low, leaving him little choice but to resign in disgrace—the only president to ever do so. In his farewell speech to the White House staff, he offered an insight that might have served him better years before. "Others may hate you," said Nixon, "but those who hate you don't win, unless you hate them — and then you destroy yourself."

Scott P. Marler is an associate professor of history at the University of Memphis.

This article originally appeared on Memphis Commercial Appeal: Watergate scandal was a look into President Nixon's mentality