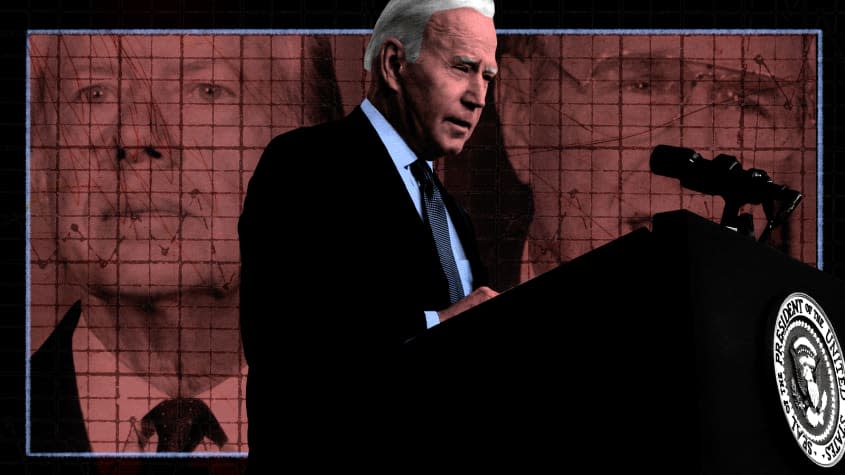

This is the way the Biden presidency ends — not with a whimper, but a boomflation?

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Sometimes when the Federal Reserve tries to squash a price surge, it also ends up crushing the economy and causing a recession. And if you're a first-term president when all that happens, you might not get a second term. Just ask Jimmy Carter and George H.W. Bush.

That is to say, whether you're a worker, an investor, a Democratic partisan, or simply a Joe Biden superfan — or all of the above — you should be deeply concerned about what's happening in the economy right now.

Yes, the American economy is running white-hot. Despite two new virus variants and global supply-chain bottlenecks, the U.S. economy grew by 5.7 percent in 2021, the fastest full-year pace since 1984. And there was more good news on Wednesday when the Commerce Department reported a 3.8 percent rise in January retail sales, almost twice the consensus Wall Street estimate.

But with that rapid growth has come rapidly rising prices. Consumer Price Index data for January showed prices jumping 7.5 percent over the past year — the highest level since 1982 — and 0.6 percent over the past month, exceeding economist forecasts. So despite all that GDP growthy goodness, real average hourly earnings actually decreased 1.7 percent from January 2021 to January 2022.

And now the Fed is preparing to act. At the central bank's meeting last month — the minutes of which were released Wednesday — officials discussed accelerating their timetable for raising interest rates, with the first one coming as soon as next month. This quickening pace is another sign of just how badly the Fed has been surprised by the sharp inflation upturn. "We're pretty far behind the curve. That's not where we wanted to be," Eric Rosengren, president of the Boston Fed, told The Wall Street Journal.

Yeah, Wall Street knows. For instance: The economics teams at JPMorgan told the bank's clients on Wednesday that it is now expecting seven rate hikes this year, up from five in its prior outlook, while continuing to look for three hikes next year. The research note cited "the increase in the January CPI, not only its size but its breadth, pointing to risks of a more entrenched inflation problem."

But, hey, is a bit of "boomflation" — fast growth plus fast inflation — really so bad? There are some Fed critics arguing that the bank should stop well short of trying to hit its 2 percent inflation target. Instead, just cool things off a bit with a few rate hikes and then hope that supply chain improvements bring inflation down further. Better to run the economy a bit hot — as wages rise and unemployment keeps falling — than risk a recession to hit some arbitrary inflation target. Fed tightenings and economic downturns tend to go together.

Unfortunately, boomflation may not be sustainable because of one of the most basic economic principles: the Law of Demand. When the price of a good rises, consumers will demand less of it. And right now, prices are rising for a broad range of goods — from appliances to cars to gas to clothing. And if consumers don't keep tolerating rising prices, they'll start spending less on all sorts of things. And that means less revenue for businesses, who'll then start spending and hiring less. And if the profit outlook changes for lots of companies, investors will start selling.

The risk: Boomflation might start looking a lot more like a 1970s-style stagflation of higher prices and high unemployment. Economist Michael Strain, an American Enterprise Institute colleague of mine, is Team Law of Demand: "So far, consumers don't seem to be pulling back their spending in the face of higher prices. But I wouldn't bet on that lasting forever — or even much longer. At some point soon, higher prices will become a drag on consumer spending and a headwind for the economy."

A further complication here is that getting inflation back to the Fed's preferred level might be really hard without causing a recession. Even if the Fed jacked up rates so far and so fast that the jobless rates jumped to 6 percent from the current 4 percent — basically reversing a year of progress — it might only bring inflation down by half a point at most, according to Goldman Sachs. Across all rich economies, the bank points out, "there has never been an increase in the unemployment rate by 2 [percentage points] that has not been associated with recession."

When the 1980 recession started in January of that year, President Carter had around a 50 percent approval rating. By the end of the recession that summer, it was hovering around 30 percent. And when the 1990 recession started in July of that year, President Bush had a 63 percent approval rating, a number that rose to nearly 90 percent when the recession ended in March 1991. Of course, the U.S. won the Gulf War in the middle of that downturn. But once the glow of military victory faded, so did Bush's popularity, falling to Carter-like levels in the summer of 1992.

Biden's approval rating is currently at 41 percent, according to the FiveThirtyEight collection of polls. It might seem like things couldn't get much worse for Biden, but history suggests it can.

You may also like

Live stream of planes landing at Heathrow Airport during storm draws surprisingly big online crowd

Watch a Clydesdale recover from injuries in Budweiser's new Super Bowl ad