It’s Way Too Hard to Put Up a Monument to Lynching Victims

Just off a street corner in Mobile, Alabama, a historic marker spells out the grisly details of Richard Robertson’s 1909 lynching. The real story told between its embossed metallic lines is about a community’s death grip on mythology and why these memorials are needed.

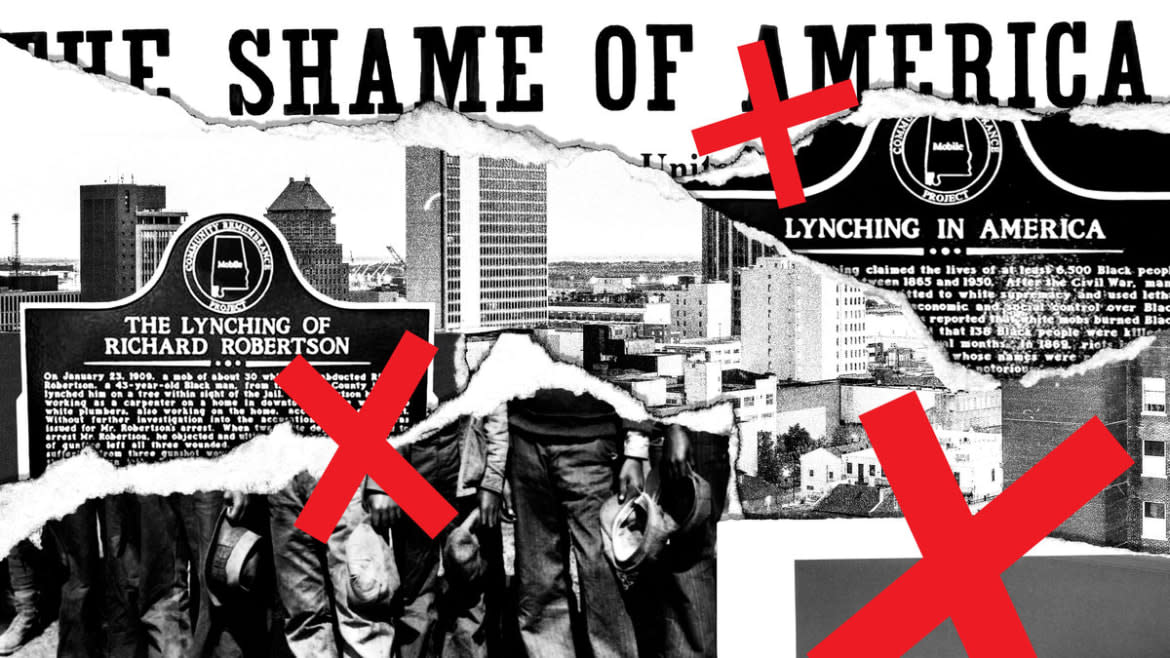

For nearly a year, the Mobile County Community Remembrance Project (MCCRP) has fought to control the Robertson plaque’s location. Paid for by the Equal Justice Initiative (EJI)—a Montgomery-based non-profit providing legal defense for wrongful prosecution and bringing awareness to historic race-based injustices—the $3,000 marker was the first in a planned series memorializing the county’s race-based lynching victims from 1877-1950. Twice now, MCCRP has navigated the required governmental processes to install the Robertson marker in public, with each of two selected sites thwarted by official powers at the last moment.

After a protracted civic fight, it was eventually placed in an obscure spot chosen without MCCRP’s approval—where it stands today.

Anti-Vaccine Insanity Is Sweeping Through Mobile, Alabama

Critics have questioned the memorial’s necessity, deeming it divisive. “Does this represent who we are now?” they ask. However, judging from the tone and substance of the pushback, elements of the lynching era might not be as bygone as they wish.

NO HISTORICAL DUE PROCESS FOR A LYNCHING VICTIM

Robertson was a Black man accused of killing a white sheriff’s deputy in January 1909. A mob pulled him from jail into the street where he was shot, then hanged. His body dangled from an oak tree for at least an hour afterward. When a federal attorney determined lax law enforcement ignored ample warning of the imminent lynching, Mobile’s sheriff lost his job.

Despite his scandalous demise, most Mobilians don’t know Robertson’s name. He is, however, enshrined at EJI’s National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama—a monument for roughly 4,400 lynched Black Americans.

EJI sparked county-level observance, too, with markers erected by local groups nationwide. Like similar memorials in South Africa and Germany, the goal is to cultivate awareness and mindful caution. Over 300 active coalitions have arisen in communities across the country with monuments erected in 20 states.

Mobile County Commissioner Merceria Ludgood—the only Black person on the commission—convened the MCCRP in 2019, the same month as the 110th anniversary of Robertson’s death. The group laid out EJI’s vision and met public sector requirements to install historic markers.

They were diligent and mindful. I know because I witnessed their process. A year prior to the group’s formation, I researched all of the lynching victims from Mobile County that are listed by EJI—Zachariah Graham, Richard Robinson, Will Thompson, Moses Dossett, Robertson, William Walker, and James Lewis. That’s why my curiosity was piqued, and my input sought.

I also knew MCCRP would meet resistance. Local culture is invested in a self-image of Mobile as “better” in race relations than other Alabama towns—more evolved than deadly places like Birmingham, Selma, and Anniston.

That perception stemmed from the 20th century civil rights work of Black Mobilian John LeFlore. He is enshrined with a public statue alongside white Mobile politico Joe Langan. One of three city commissioners from 1953-1969, Langan's more inclusive perspective helped desegregate facilities and hire a handful of Black police officers.

But even LeFlore recognized Mobilians’ fables. In 1970, he said, “We believe the matter of Mobile being unsurpassed…in good race relations is a myth.” He praised federal powers and civil rights actions that took place in cities like Selma, Birmingham, and Montgomery—which “eased our situation” and created “a favorable sort of climate that would not have otherwise existed.”

Mobile would always be a former Creole frontier town made fantastically notable by King Cotton. The antebellum era and Jim Crow sentiments were foundational to its relevance. And its legacy of lynching can’t be swept under the rug of history.

In 1906, Mobile mobs threatened Will Thompson and Dick Robinson—two Black prisoners accused of assault—to the point authorities moved them to Birmingham for safekeeping. Immediately afterward, a catastrophic hurricane struck. Newspaper headlines read, “NEGROES LOOTING HOMES OF DEAD” and blamed Black Mobilians for theft and corpse mutilation.

Days later, a lynch party of hundreds met the train that returned Thompson and Robinson to Mobile for trial. One vigilante told the accompanying press his colleagues were “leading businessmen of Mobile.” They admitted lynching was undertaken outside city limits to intentionally avoid leaving “a stain upon Mobile that would take years to wipe out,” the Daily Item, a long defunct area newspaper, reported.

The mob marched the prisoners toward Africatown, a community of independent-minded Blacks, descendants of captives from the nation’s final slaving ship. On its outskirts, the crowd killed the prisoners. The victims hung in the trees from midday to afternoon while thousands of Mobilians streamed northward on the streetcars to gawk at the grisly spectacle. Postcard photos were snapped. Souvenirs were nicked from the victims. (A year later, Moses Dossett was hanged from the same tree in a driving storm.)

Less than three years later, Lynch law was clearly in the air when Robertson was delivered to jail, accused of killing a sheriff’s deputy. In short order, the mob dragged him into the street and murdered him. His murder’s direct negation of law enforcement, plus its location at the heart of downtown, made it both unseemly and unignorable—all of which made it a natural choice for MCCRP’s initial plaque, to draw attention to oncoming memorials.

The historical marker commemorating Richard Robertson was set to be placed where a statue of Confederate Adm. Raphael Semmes had previously been.

THE POLITICS OF MEMORIALS

To memorialize Robertson’s lynching, the group chose the median at the intersection of Royal and Government streets as the location—a place of distinction where defiant Confederate Adm. Raphael Semmes stood immortalized in bronze for 120 years until its 2020 relocation to the history museum.

The city signed off on MCCRP’s wishes, until Mayor Sandy Stimpson rescinded approval just before the Jan. 23, 2022, unveiling. The mayor thought the location too contentious—local Confederacy enthusiasts were sore—and suggested a place diagonally across Mardi Gras Park, closer to where Robertson was killed.

MCCRP regrouped and chose a new location outside the main entrance to Government Plaza, the city and county’s primary office and courthouse. Once again, they successfully navigated the permitting process. County commissioner Ludgood said she escorted fellow commissioners Connie Hudson and Randall Dueitt to the site in April, where neither voiced strong opposition. Ludgood said the only concerns were in regards to whether the plaque would be in the city right-of-way.

Just days before the scheduled July 9 dedication date, MCCRP member Karlos Finley called Ludgood. He had just been contacted by journalists asking him for a statement about the marker currently being erected on the backside of the block— away from the Government Street locale. He was gobsmacked.

Mayor Stimpson had taken matters into his own hands, and directed the plaque be embedded in concrete at the spot he suggested in January, rather than the location MCCRP chose. The mayor told Ludgood that his unilateral decision was prompted by commissioners Dueitt and Hudson’s written objections. And yet, the mayor insisted that this new, more obscure location demonstrated his intention that Robertson’s marker would remain in public view—and he reiterated his support of MCCRP’s goals.

In Dueitt’s letter, which The Daily Beast acquired through a public records request, the former law enforcement officer turned public official maintained his experiences kept him from agreeing to any memorial “honoring” someone accused of killing a deputy. He opposed its existence. (A representative in Dueitt’s office told The Daily Beast he had no further comment and deferred to the reasoning stated in his letter to Mayor Stimpson.)

Hudson, in a separate letter, claimed a marker location near Government Plaza’s main entrance would impede foot traffic. She didn’t mention the bank of 10 newspaper machines just a dozen yards away—closer to the street corner and the building—which presented more of an obstacle than the planned memorial post and plaque next to a small tree. She later agreed that Robertson’s accused crime created a “cloud of suspicion” worthy of pause.

Ludgood asked Mayor Stimpson to remove the marker for fear they weren’t adhering to EJI’s required process, putting MCCRP in violation of the agreement. To enhance her point, she noted Robertson’s lack of due process. Were he adjudicated, rather than murdered by a lynch mob, the memorial wouldn’t exist.

In the course of my research, I uncovered evidence that one initially listed victim was erroneously included.

William Walker vanished after being chased into a wooded area but was eventually extradited to Mobile from coastal Mississippi. He was adjudicated, then executed by the state. I supplied MCCRP with that information. They consulted with EJI and had Walker’s name removed from their list. Their actions gave substance to Ludgood’s contention about Robertson’s legal status.

Were Robertson tried, things would be different. Mob violence and the absence of rule of law was the essence.

When MCCRP members heard about their marker being commandeered, they were incensed. But EJI advised them to drop the argument, since every time MCCRP made a public statement, the press would be compelled to give voice to those working against them. Opposition would cloud the picture by shifting focus to Robertson’s accused crimes and not the absence of due process, EJI argued to its allies at MCCRP.

EJI warned that having these fights in public has hampered memorial efforts in other locales. It was employed to block a plaque in Lafayette County, Mississippi, another in Madison County, Tennessee, and another in Davidson County, Tennessee. EJI told of other groups who had to resort to using private property for memorial markers since public backlash was so strong. To paint it as somewhat of a victory, EJI noted that Mobilians, at least, had their marker erected on public land when it was all said and done.

Previous clashes among Mobile county commissioners also demonstrate an impossible desire to have it both ways—reckoning with Mobile’s violent, racist past, while also acting is if it were an especially forward-thinking region during the lynching era.

When Ludgood—the commission’s only Black member—suggested in 2020 that the county stop recognizing Confederate-themed holidays, Hudson resisted, citing a “sensitivity on both sides.”

“There are citizens who feel this is part of history, part of their heritage,” Hudson said. “The vast majority, slavery issue aside, had ancestors who fought in ‘The War Between the States’ and the vast majority of those were not slaveholders. They were poor farmers who felt like they were protecting their homeland.”

When Ludgood noted systems of white supremacy, Hudson called the issue “a whole lot more complicated than that” and said we “can’t change history.”

It is worth noting here that the “poor farmers…protecting their homeland” for whom Hudson advocates were essentially traitors—firing on U.S. troops, soldiers who pledged an oath to the U.S. Constitution and operated as an extension of that legal framework.

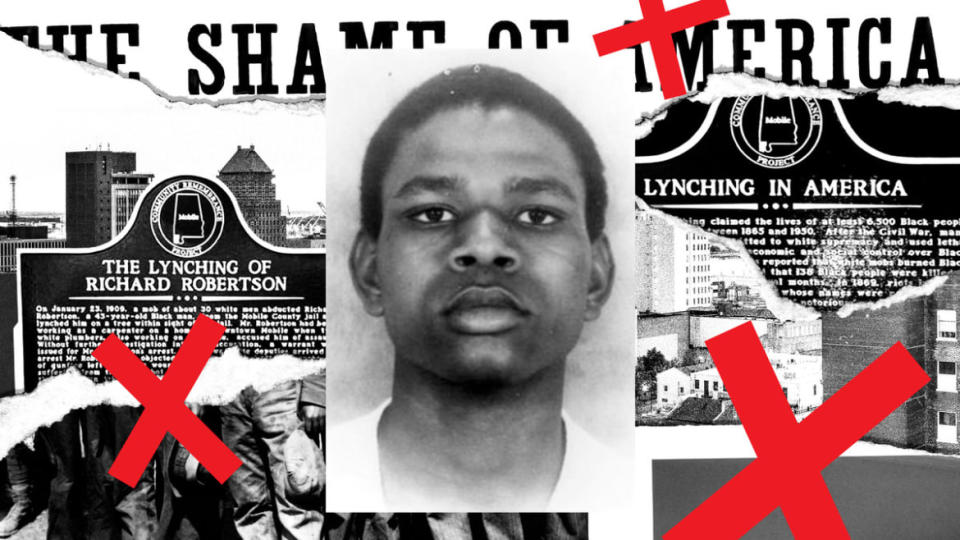

Michael Donald, who was lynched in 1981.

Cognitive dissonance riddles the argument that traitors to the United States deserve holidays in their honor, while one accusation of shooting a cop doesn’t merit someone else a modicum of due process—even a century after being murdered by an extralegal mob.

What’s more, Mobile’s history of injustice extends far beyond the lynching victims on EJI’s list. Boston’s Civil Rights and Restorative Justice Project erected a memorial and hosted a museum exhibit calling attention to six Mobile victims of unatoned, race-based killings from the 1940s. Hell, lynching happened in the 1980s, with Mobilian Michael Donald being murdered by a lynch mob in 1981.

The grousing about these plaques and historical activism persists in Mobile. Critics decry efforts to end Lost Cause reinforcement. One local pundit compared those agitated by Confederate statuary and lynching memorials to children squabbling over toys.

A community truly “past” these crimes doesn’t get ruffled over a modest memorial marker appearing on public land.

How a Detective Who Was Blamed for One Lynching Solved Another

The lynching memorials are pertinent in the same way Holocaust memorials are—because the human condition hasn’t innately changed in the last 120 years. Around the world, we’re the same messy, violent creatures we’ve long been. Our capacity for injustice and savagery is always there.

It’s difficult to grow beyond those things you are least proud of until you come to grips with them. As EJI maintains, “justice is a constant struggle.” You can’t commit when you choose to forget.

It is doubtful MCCRP’s other planned memorials will meet the same resistance. They are scattered across predominantly Black neighborhoods, far from the city’s center and the eyes of elected officials, court officers and tourists.

In a cruel twist of fate, the aims of those long-ago lynchers—relegating Mobile’s despicable aspects to overlooked corners, a distance made for easy denial and comfortable ignorance—never really died after all.

Get the Daily Beast's biggest scoops and scandals delivered right to your inbox. Sign up now.

Stay informed and gain unlimited access to the Daily Beast's unmatched reporting. Subscribe now.