Threats, technical issues on Election Day 2022 captured in Arizona poll workers' reports

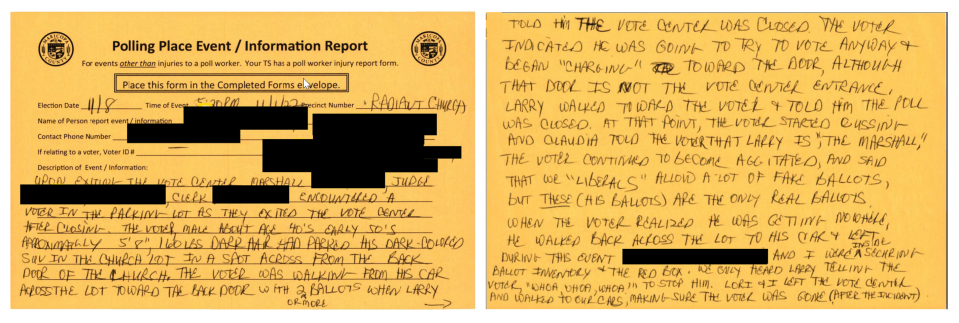

As a group of poll workers — two Democrats and one Republican — were leaving a voting center in Sun City on the evening of Nov. 1, 2022, they encountered a voter in the parking lot.

The dark-haired man, 5-foot-8 and about 160 pounds, was holding two ballots and walking toward the polling place.

When the group told him it was closed, he quickly became irate.

“The voter indicated that he was going to try to vote anyway and began ‘charging’ toward the door,” according to a report on the encounter filed by Annarose Lilly, a Democrat and the voting location's head poll worker.

Another worker "walked toward the voter and told him the poll was closed. At that point, the voter started cussing. ... The voter continued to become agitated and said that we ‘liberals’ allow a lot of fake ballots."

The Sun City incident is one of 66 politically charged disruptions and conflicts between poll workers, election observers and voters during last year's general election reported to officials in Maricopa County.

Elections professionals nationwide continue to face intense scrutiny after unfounded allegations of widespread fraud surfaced during the 2020 presidential race. In Arizona, local elections officials have seen an onslaught of threats that have driven some from their jobs. They have long warned that conspiracy theories spread by some Republican officials and candidates could manifest in conflicts at the polls.

Reports made by poll workers and voters during the 2022 election show some of those predictions have become reality. Election officials are concerned about how they'll keep poll workers safe — and what effect increased hostility at the polls will have on voter turnout, poll workers and polling sites.

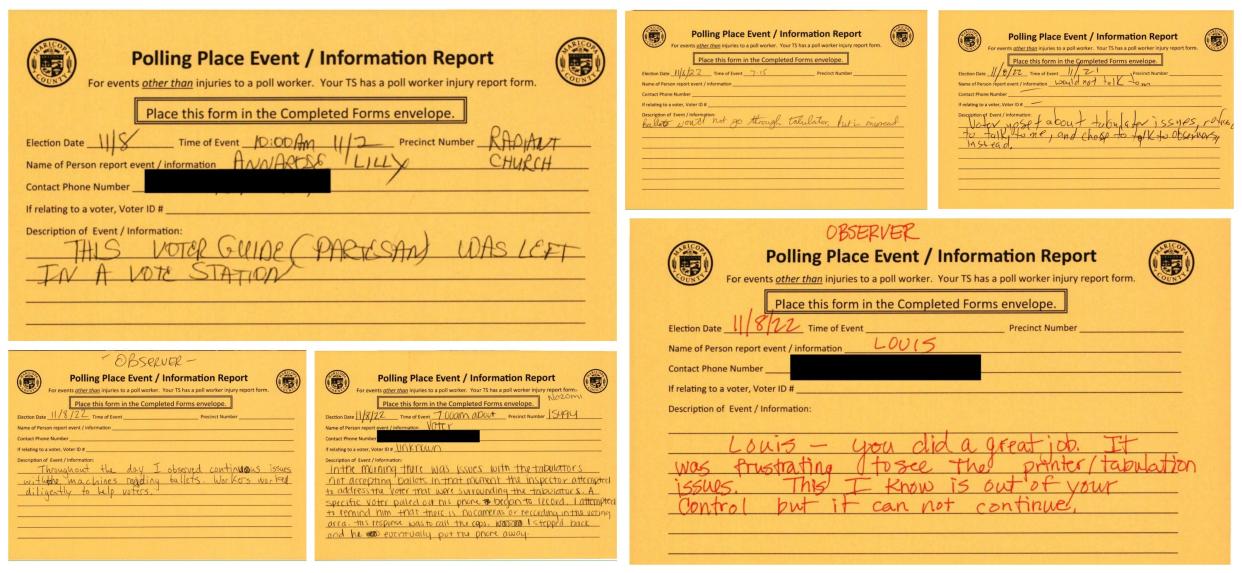

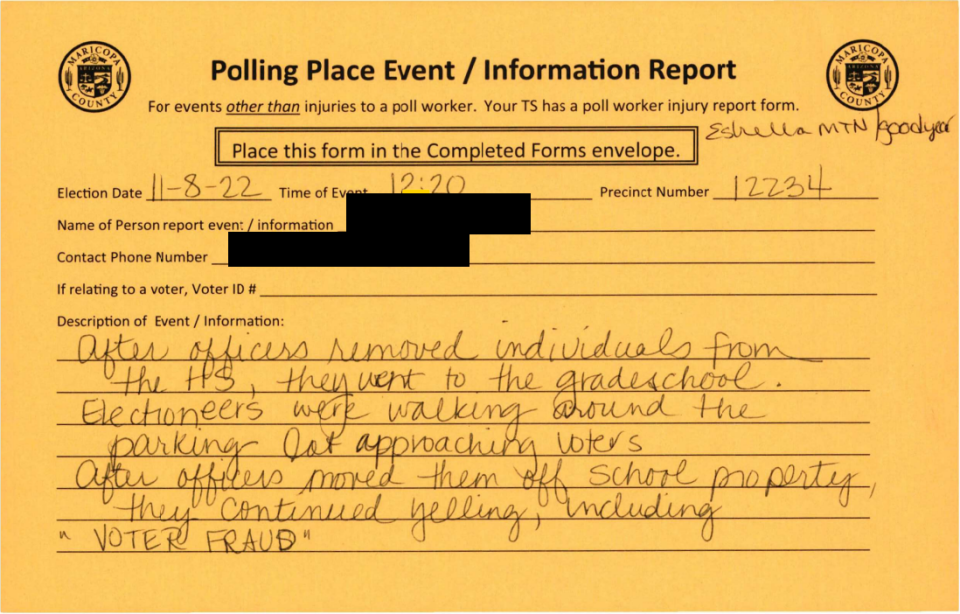

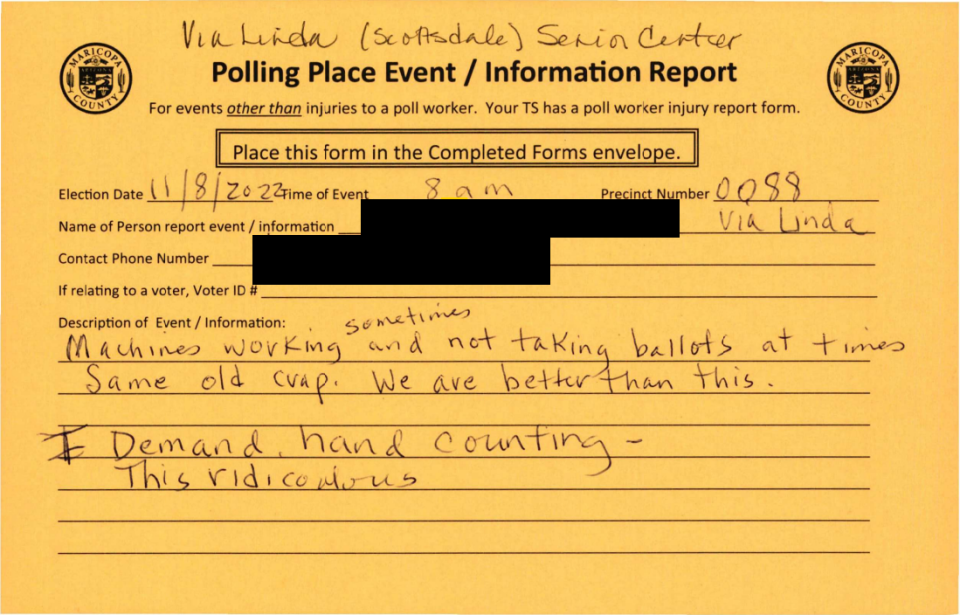

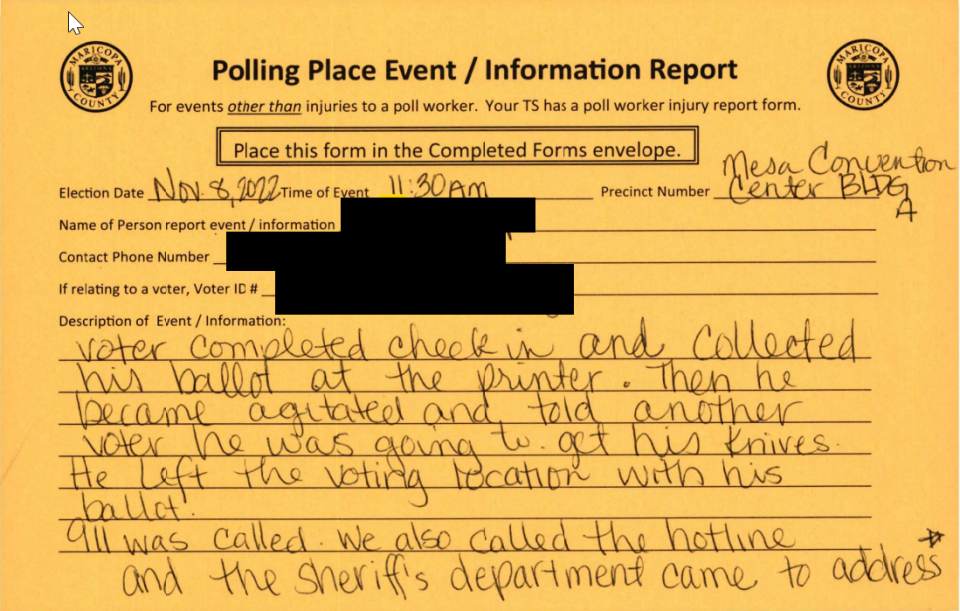

The reports, called "goldenrod forms" because of the color of the paper they are written on, are filled out by poll workers — and sometimes observers and voters — to make notes and document problems at polling sites. They offer an insider's view into the challenges and experiences of election workers in the state's largest county on Election Day. The Sun City report was dated Nov. 1, during early in-person voting, but most were written on Election Day.

Not all interactions documented by the 2022 election reports were as hostile as the one in Sun City. Some were more banal and resolved quickly.

For instance, one poll worker wrote of asking a family to stop taking selfies inside a polling place. The images violate state law, which bans anyone from taking photographs while inside or within a certain distance of a voting location. The family agreed, apologized and went on their way.

But many describe threatening behavior that appears related to election conspiracies.

While reviewing the nearly 500 reports submitted for the November election, The Republic found:

Reports of tensions between poll workers, observers and voters were mentioned in about 14% of the forms. Poll workers and election officials said the number of incidents increased in 2022.

A majority of the reports mention the printer problems that plagued many of Maricopa County's polling sites on Election Day or other technical issues. These reports reflect election workers' frustrations as equipment issues led to long lines and angry voters. In some cases, voters saw the problems as proof of election fraud.

A handful relate to low supplies and lines at polling sites.

A small number report mistakes by poll workers, which were either corrected on the spot or documented for election officials to resolve later. For instance, a poll worker reported on one form that she accidentally mixed up two voters' ballots, but canceled and reprinted them.

A few of the notes mention instances in which officials with the U.S. Department of Justice entered polling sites. Maricopa County was one of five Arizona counties and 64 jurisdictions nationally where the DOJ monitored polls for compliance with federal voting rights laws.

Just over 100 forms contain other accounts that couldn't be categorized. These include everything from short, end-of-the-day notes from observers — "Everything ran smoothly," wrote one Republican observer at the end of her shift in El Mirage — to reports of medical emergencies among poll workers and voters. The forms are handwritten, and in some cases, The Arizona Republic couldn't fully decipher the accounts. Other reports had so few details that they couldn't be categorized.

The Republic reached out to Democratic and Republican workers involved in the incidents described in the forms. One wouldn't agree to talk on the record, citing concern for her personal safety, and six others didn't return The Republic's calls.

Some of those who did agree to speak acknowledged that they might receive harassment and backlash for doing so.

"Maybe I'll regret this, but I'm just like, 'I am not going to be intimidated by these bullies,'" Lilly said. "That's it."

This summer, election officials are focused on finding polling locations for 2024 and keeping everyone safe. Maricopa County Elections Director Scott Jarrett said he is concerned about ballot drop box observers and conflicts at the polls, but also worries that reports of such incidents will cultivate fear around elections, making voters think twice about turning out.

"It's incredibly frustrating that we have people that don't have confidence in this process," Jarrett said. "And it's because there is a well-resourced campaign to build that distrust."

Forms document conflicts, disruptions and electioneering

At an unidentified polling station, a poll worker approached a voter openly carrying a gun. Initially, the man said he was unaware that he couldn't bring his weapon into the voting center but later admitted that he knew it was illegal, the poll worker wrote.

At Sunrise United Methodist Church in Phoenix, a woman in a white SUV parked near the entrance to the polling station and screamed at voters as they walked in to cast their ballots.

And in another report, a lawyer entered Palm Lane Elementary School in west Phoenix to speak with a Republican observer about "proper identification of a voter and other issues."

"He didn't ask poll inspector or staff about permission to be here," the report notes.

All are evidence of problematic Election Day scenarios that have increased in recent years as electoral distrust has grown, Jarrett said.

Every election has conflicts, he said, and with more in-person voters in Maricopa County in 2022 than in 2020, it makes sense that there might have been an increase in disruptions last year. But he doesn't believe an increase in in-person voters entirely accounts for the uptick in polling place disturbances. At least some of the increase is attributable to distrust of elections, he said.

And, he said, the reports of electioneering, conflicts, threats and disruptions contained within the goldenrod forms are likely an undercount of such incidents. Jarrett said he's received other reports of concerning activity via the Election Department's poll worker hotline and in post-election conversations with staff and representatives of voting locations. Additionally, poll workers at some voting sites that didn't turn in any goldenrod forms still said they experienced disruptions and threatening behavior from voters.

Politically charged voting disruptions and conflicts aren't limited to Maricopa County. Local election officials across the country have reported threatening behavior at the polls, according to David Becker, executive director of the Center for Election and Innovation Research, a nonpartisan organization that works to build confidence in elections.

"I hear these stories all the time from election officials where they tell me that they've heard their poll workers have experienced harassing conduct," he said. "These aren't widely reported all the time."

Printers, tabulators played into false voter fears, forms show

Erin Smith was nervous coming into the November election.

She already had worked a rough August election where county-issued pens smeared some ballots. The problem only occurred at a few voting locations, and nobody was prevented from voting, but the issue annoyed voters and Smith, a Republican, said she endured a long shift filled with irate people.

As a troubleshooter, she was tasked in November with addressing any issues that might arise at several polling sites in the northern part of the county, including Desert Hills Community Church and Outlets at Anthem. The first 20 minutes of Election Day went smoothly, she said, and then the tabulators at one of her sites began rejecting ballots.

"The mood of the building changed," Smith said. "People immediately got pissed off."

Things went downhill from there, she said. Nobody directly threatened her with violence, but she was cursed at and berated by frustrated voters. Several hurled insults at her and a few tore up their ballots, threw down the pieces of paper and walked out, she said.

No goldenrod forms were turned in for either of the polling sites Smith worked, showing that these records underrepresent the number of issues experienced at polling places last year.

A number of the forms reviewed by The Republic that were submitted by voters mentioned printer problems. Some also expressed discontent with tabulators and pushed for a hand count in Maricopa County.

"Machines working sometimes and not taking ballots at times," one voter at a Scottsdale polling location wrote. "Same old crap. We are better than this. I demand hand counting. ... This is ridiculous."

Proponents of hand counting argue that it is more secure and would increase trust in elections. But tabulators are air-gapped — disconnected from the internet and from other machines that might be connected to the internet — and numerous studies have concluded that human error could make hand counting less accurate than a tabulator count.

There are also many logistical barriers to the idea, including costs and staffing needs, and Arizona Secretary of State Adrian Fontes recently warned that hand counts might violate state law.

Other voters took the printer problems as proof of fixed election results. A voter in Sun City wrote that he "reluctantly" submitted his ballot via a secure box used for tabulator misreads after attempting to cast his vote several times at two different polling sites. The box, known as "door 3," allows voters to drop their completed ballots into the tabulator to be counted later at the county's election facility.

"I don’t feel comfortable about this coincidence," the voter wrote.

Smith said she went home "traumatized" by Election Day.

"When you're surrounded by a crowd of very angry people, they don't really have to make direct physical threats," Smith said. "It's an extremely uncomfortable experience just by itself."

Keeping voters and election workers safe

The day after the Sun City incident, which took place early in the in-person voting period, the voting location's head poll worker called an all-hands morning meeting.

Lilly and her team were concerned the man from the night before might come back, she said, perhaps with weapons. They wanted to be ready in case he did.

"We just kind of went through it," she said. "We just said, basically, 'If somebody comes in here with a gun, what are we going to do? We're going to get out as fast as we can. So, always watch your back and know where the exits are.'"

One of her poll workers contacted the Sheriff's Office asking for deputies to provide additional security at the polling site. Initially, Lilly's team hoped a deputy could be on-site when they were in the building.

But law enforcement can scare away voters, Jarrett said, and balancing that concern with security needs is often a complex decision.

"When that call came in, it was me working with the Sheriff's Office on what was the best response — what they could provide, what we felt comfortable with," he said. "And definitely having a sheriff's presence outside a voting location during operations was not something that we felt comfortable with."

Instead, Jarrett told Lilly and other poll workers at the Sun City site that a deputy would sit in the parking lot at closing so that they could safely get to their cars.

In an urgent, life-threatening situation, deputies would still respond as normal, Jarrett said. In most cases, however, election workers are encouraged to try de-escalating the situation themselves rather than calling law enforcement for help. Jarrett said de-escalation techniques to calm upset voters have become a major part of poll worker training over the years.

When law enforcement does need to respond to the polls for an incident, they typically do so in an unmarked vehicle and not in full uniform, Jarrett said.

So far, that system has worked. Lilly said the man who her colleagues encountered in the parking lot didn't come back. Amid the printer problems on Election Day, she worried that her team might "have an insurrection on our hands," but she and other poll workers — whose pay started at $12.80 per hour — successfully defused situations that arose throughout the day.

"It's a matter of survival," she said. "If we don't de-escalate, our lives could be at stake. ... We are the first line of defense. Whether it's fair or not, that's the way it is."

Will poll workers come back? Election officials brace for 2024

Although cases of harassment and threats of violence are becoming more common nationwide, the vast majority of election workers and voters aren't impacted, said Becker, the Center for Election and Innovation Research head.

"The number of voters or poll workers affected by this are probably in the hundreds nationwide out of hundreds of millions of voters and poll workers," he said.

But he and Jarrett worry that broader perspective might get lost in reports of such incidents and drive away voters from the polls. Becker said he encourages concerned voters to mail in their ballot or vote early since most incidents tend to happen on Election Day.

Jarrett is preparing for the 2024 election cycle by expanding de-escalation training for poll workers. He'll also begin meeting with the Sheriff's Office and other law enforcement partners as voting draws closer, he said.

In the meantime, he's worried about finding churches, schools, community centers, shopping centers and other places willing to serve as polling locations.

"We're hearing feedback from our facilities that are not wanting to be voting locations because of electioneering going on," he said, adding that roughly 50 locations that served as polling sites during the 2020 election didn't come back for 2022.

Finding poll workers, he said, is less of a concern. Although some who worked on Election Day may not come back, it's normal for a significant number of election workers each year to be new to the polls, Jarrett said.

Lilly said she intends to return. Most of her fellow poll workers from the Sun City site who are planning to sit out future elections will do so for reasons unrelated to fear or harassment, she said, although she knows of one who won't come back because he was so infuriated by verbal abuse from voters.

"He was just not going to take it," she said. "He wasn't afraid, but he was angry."

Initially, Smith was so frustrated by her experience as an election worker that she didn't plan to work the next cycle.

"I was super, super pissed," she said.

Her mind has changed since then, she said. If she has the opportunity to work another election, she'll take it.

"We need people to do this sort of stuff," Smith said. "And it would be wrong for me to encourage people to do it when I am unwilling to do it myself. We have to have elections, and we have to have people who run these elections, and we have to have people from across the political spectrum that are willing to pitch in."

Sasha Hupka covers Maricopa County, Pinal County and regional issues for The Arizona Republic. Do you have a tip to share on elections or voting? Reach her at sasha.hupka@arizonarepublic.com. Follow her on Twitter: @SashaHupka.

Eryka Forquer contributed to this report.

This article originally appeared on Arizona Republic: Maricopa County 'goldenrod' forms detail Election Day tension at polls