Weaverville's Ziffer, a former Mars Hill professor, reflects on surviving the Holocaust

WEAVERVILLE - There are not many Holocaust survivors left, but there's at least one in Western North Carolina, and he has ties to both Buncombe and Madison Counties.

Walter Ziffer, 95, of Weaverville, was an adjunct professor at Mars Hill University from 2001-15. Ziffer and his wife, Gail, moved to Weaverville in 1993.

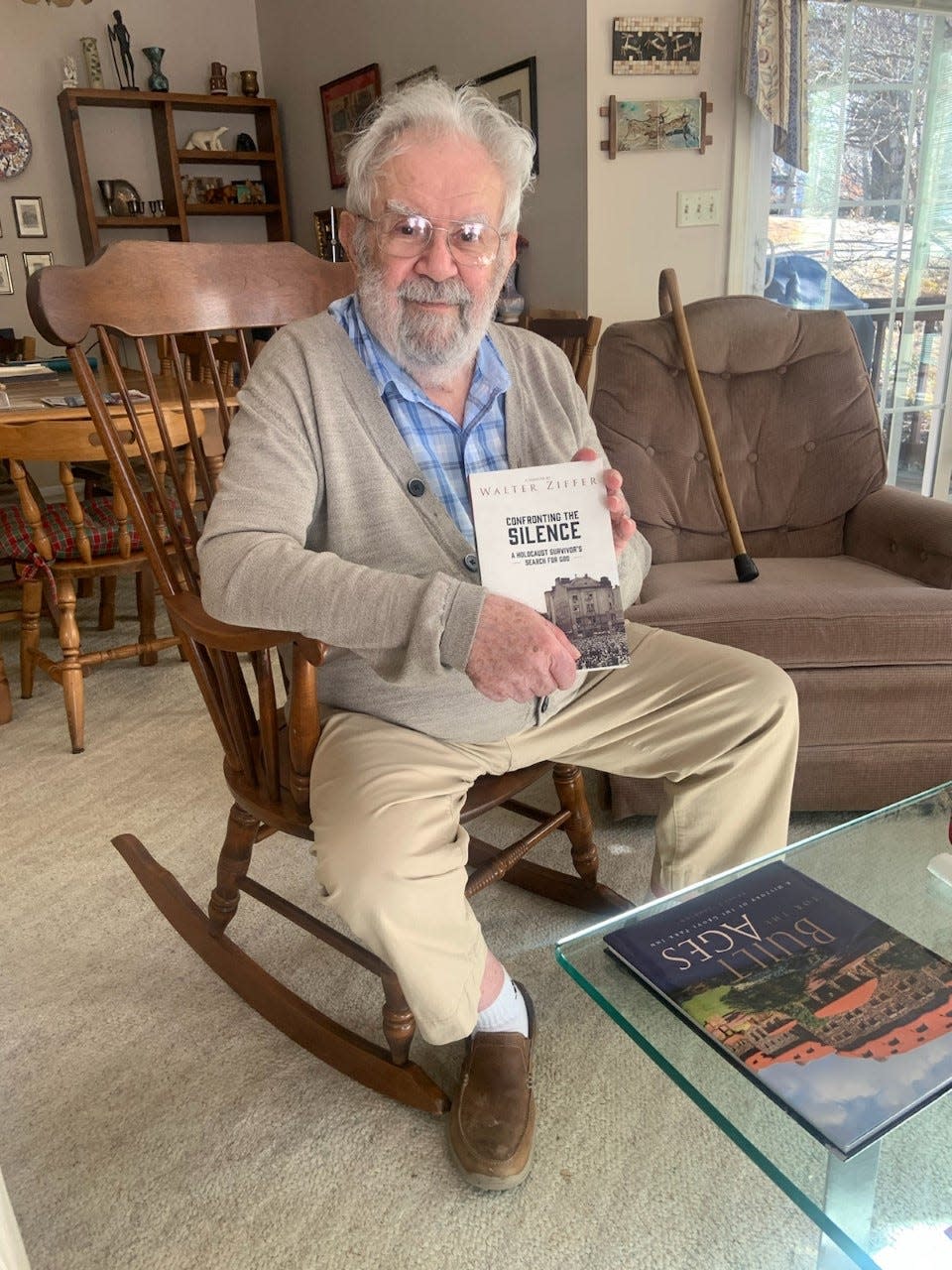

Ziffer also wrote a memoir on his experience, "Confronting the Silence: A Holocaust Survivor's Search for God."

Ziffer's 14 years at Mars Hill came in his "retirement years," he said, as most of his teaching was done in France, Belgium and Washington, D.C. While at Mars Hill, he taught Biblical studies - including Hebrew language studies - as well as theology.

But Ziffer's journey to Mars Hill is an exceptionally improbable one.

He survived seven concentration camps, or what he calls "death/extermination camps" after being captured in his native Czechoslovakia when he was 15. He was not freed until three years later, at 18.

"I was taken into the camps with between 30 and 40 young people, and only two survived," Ziffer said. "The other survivor came to Israel after the war, and I came here to America."

After Ziffer's experience in the Holocaust, he anticipated that after coming to the U.S., people would want to hear about his story but found that not to be the case.

"Coming back now, (I thought), 'Why didn't the people ask me questions?'" Ziffer said. "I think they had guilty feelings, or they didn't feel comfortable asking questions. When I married my former wife, Carolyn, I started going to church, of course, and the people there were very interested. They asked a lot of questions. They wanted to know what it was like. So you can see ... I appreciated the interest. That was one of the things that drew me to Christianity."

"There weren't, until recently, young people who went into the ministry," Ziffer said. "Some of them wanted to know Hebrew and Greek. That used to be something anybody who went to a Christian ministry had to study."

Conversion to Christianity

Ziffer's own journey to the Christian ministry came following his arrival to the United States.

His decision to convert to Christianity was jump-started on his first day in the United States after moving to be near family in Nashville, Tennessee.

"I came to America in 1948," he said. "I had an uncle in Nashville, Tennessee, and he helped me, along with some other organizations that helped me as well. My relationship with the Jewish community in Nashville was not very good.

"I still haven't quite understood it, why a lot of Jewish people don't want to deal with the Holocaust. They don't want to talk about it. They don't understand it. Most people don't understand it, why and how it happened. So, I really didn't have a really good relationship with my uncle."

While in Nashville, Ziffer earned an engineering degree from Vanderbilt University. According to Ziffer, two friends in Franklin, Tennessee, also helped him realize he wanted to explore the idea of converting to Christianity.

"During summer school (at Vanderbilt), I met two young people ... and we became good friends," Ziffer said. "Both were Christians, and I had a wonderful experience with them. Eventually, the fellow had to leave Nashville because he wanted to study medicine in Memphis.

"He came to me once and said, 'Look, I just lost my father, Mr. Otis Grant, in Nashville, and my mother is a widow. Would you consider moving in with my mother and be her surrogate son?' I would cut the grass and take her to church, things like that. So I left my uncle and went to live there. I became interested in Christianity that way."

Shortly after graduating from Vanderbilt, Ziffer and his first wife, Carolyn Kinnard, had their first child and moved to Dayton, Ohio, where Ziffer worked as an engineer at a division of General Motors.

While in Dayton, Ziffer began attending church with his family, where he was drawn to the sermons of a particular pastor.

"That pastor was a remarkable person, whom I like very much," Ziffer said. "At one point, I just wanted to be like him. He was a mentor. So, at that point anway, I said, 'I would like to become a minister like you are.' So, we decided then on Oberlin, because at Oberlin College - it's no longer there - was a Graduate School of Theology."

Ziffer earned two master's degrees - one in Biblical Studies and the other in The New Testament and Greek Language - from Oberlin while working as a student pastor in Gibsonburg, a small town south of Toledo.

Purpose in writing the book

It took Ziffer about two years to write the book, he said.

While many of Ziffer's American peers may have been reluctant to discuss the horrors of his Holocaust experience, Ziffer was quite candid about his experience in the book, so much so that his daughter, after proofreading some of the book, recommended he cut back some of the content detailing his traumas.

According to Ziffer, the book is an abbreviated version of a 400-page work he wrote for his family.

"I wanted to be sure my children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren - I have six of them, all in Florida - that they get that story," Ziffer said.

However, two of Ziffer's daughters felt the subject matter in those 400 pages was probably too personal for some readers, as the book discussed Ziffer's divorce from his first wife and her more than 10-year struggle with mental health issues. The couple were married more than 30 years.

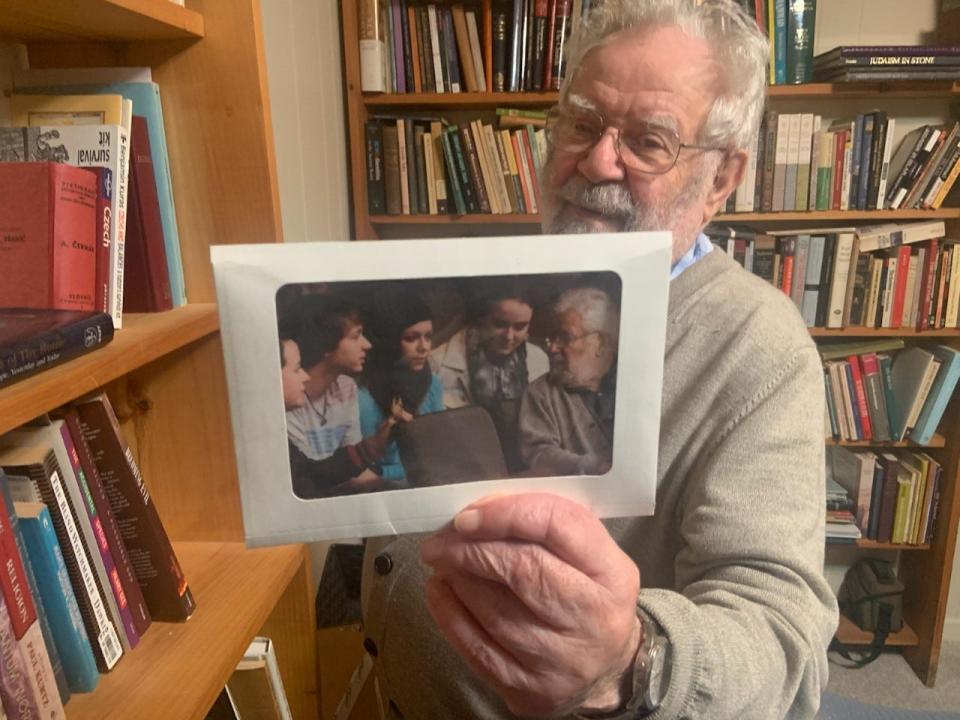

While telling his story to his family was important, Ziffer has also made a point to meet with students - both locally and internationally through Zoom - to talk about his experiences.

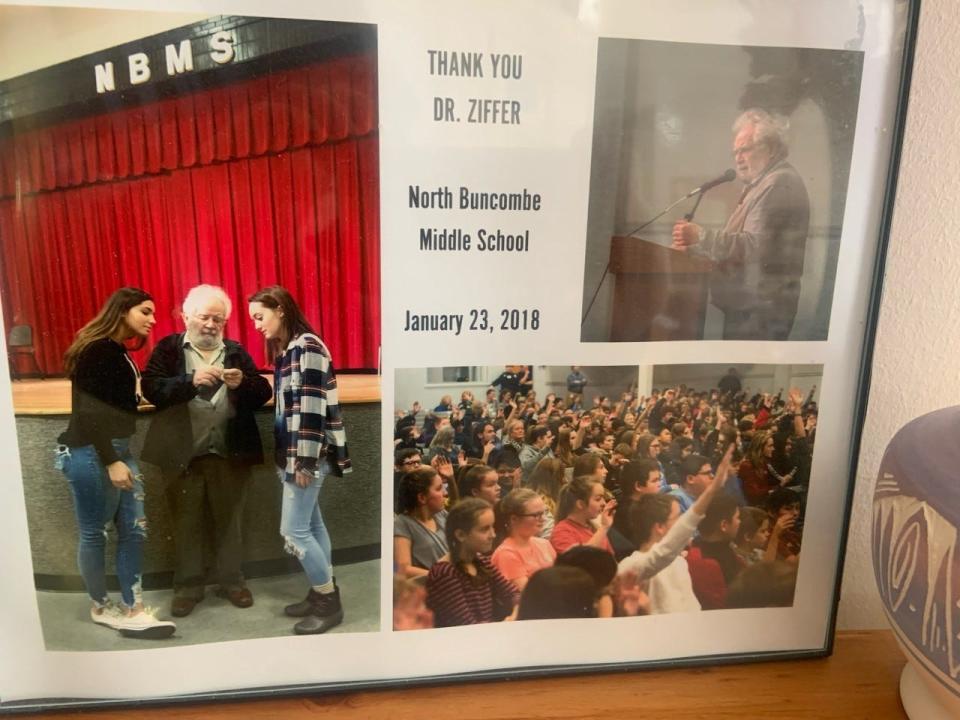

In 2018, Ziffer met with students at North Buncombe Middle School.

His experiences in the camps

According to Ziffer, one aspect that helped him survive was his ability to speak German.

"I just survived. There were others of course that survived too, but let me say that one of the major things that helped me was that I spoke German fluently, because that's one of two native languages - German and Czech," he said. "Both my parents are from Austrian and German background. We spoke German at home, and I went to Czech school. My sister went to German school in Czechoslovakia.

"So, me speaking German was a tremendous plus, so if a German came up to me and gave me a shovel and said, 'Do such and such' in German, I knew what to do, and I usually did it well. I was between 15 and 18 years old. There were a lot of Polish-Jewish people in this camps, who, well, they didn't speak German. When the German engineer came up to them and said, 'Do such and such,' they looked at him and didn't understand. And when that happened, they were beaten up. And some people were killed. Most of them were killed, eventually. That was the German plan: to kill all the Jewish people in Europe, and then in the world."

The other factor in Ziffer's favor was pure chance, or "luck."

Remarkably, not only was he one of two survivors out of the group of more than 30 children captured, but his parents and sister also made it out alive.

The first camp Ziffer was transported to was Sakrau.

"On the average - some camps were better, some worse - but in the evening we got between 10 and 12 ounces of bread. In some camps, a tiny piece of margarine, but in most camps, nothing. We all had a bowl, and they gave us some soup. At the beginning, it was better than towards the end because as Hitler was losing the war, things became worse for us, too.

"In the morning, we got lukewarm water. Black water. They called it coffee. It was not coffee. I don't know what it was made of. At noon, they brought out soup in kettles, and that was made usually of potato peels and beet peels. That was it. We were hungry every day, every day, every day."

He weighed 87 pounds when he was rescued by the Russian army.

Despite the book's title, "Confronting the Silence: A Holocaust Survivor's Search for God," Ziffer said his primary focus in the concentration camps was not on a relationship with a higher power but rather on survival.

"We were in such a terrible state of mind to speculate and to think," Ziffer said. "There were just a few things on our minds: number one, to get the food that we were supposed to get without having it stolen from us. You get one piece of bread at night. Now, that's the only piece of bread you're going to have for 24 hours. The bread could be stolen by someone else, who is just as hungry, or even hungrier. So, I figured that one out and ate the whole thing.

"The second thing was to make yourself, so to speak, invisible, because when you were visible, you usually got beaten up for the slightest thing. If you had a shovel and the handle broke, that was your fault. So, you got beaten up. And some people didn't survive those beatings."

Ziffer recalled a time when he took a beating as well.

"In my second camp, the only place where there was heat during the winter was one particular place where the prisoners made boots for the Germans," Ziffer said. "There were internal camp police, who were called 'capos,' were also prisoners but were one step higher than us. That place had a wooden stove, because when you make shoes, you have to melt certain waxes and stuff. It stank in there. I went in there to warm my hands, and the camp commander came in there, Mr. (Kurt) Pompe, and saw me there and said, 'What are you doing here, you filthy Jew?'

"I said, 'Sir, I'm warming my hands.' And he said to me, 'Well that's interesting. I'll warm up another part of your body.' He stepped out, he whistled, and three capos came. I had to take off my clothes and bend over a little chair used for the people who made these boots, and he beat me up. He hit my back and my behind, and I passed out after about nine whips. It was just incredible. It's ... I don't want to remember that."

At another camp, Ziffer was delegated to be the assistant to a Ukrainian locomotive driver.

"The locomotive was fired with blocks of coal dust that were pressed together like a brick," Ziffer said. "I had to stack these things around the kettle of the locomotive. Every time the train was filled, the locomotive has a hard time pulling this while the wheels are spinning, and the whole thing is shaking. What I had very carefully built filling these little bricks, this man beat me up every time. The last time this happened, he threw me out of the locomotive - literally kicked me out - about 10,000 feet away from the place where they filled up the locomotive with water. He just drove off. I had to run behind the train to fill up the locomotive after I had been beaten up and insulted. It's hard to understand how people can do this to other people - to a child."

His spirituality now

Ziffer refers to himself as a "Jewish secular humanist."

"So, secular means, I don't believe in anything that is not natural," Ziffer said. "I don't believe in gods. I don't believe in miracles. None of that, because what seems as a miracle today, 10 years from now may be understood.

"When I say humanist, I mean by that that I have trust in what we can, as humans, accomplish, if we are serious. Wars don't have to be, don't have to happen."

As such, he said he felt the story of his survival is an important one to tell.

"The story is important. I'm not interested in my name getting out," Ziffer said. "I'm 95 years old, so what the heck. I don't know how much time I have left. But the story is important."

Walter Ziffer's book, Confronting the Silence: A Holocaust Survivor's Search for God is available on Amazon.

Please help support this type of journalism with a subscription to the Citizen Times.

This article originally appeared on Asheville Citizen Times: Former Mars Hill professor Ziffer reflects on surviving the Holocaust