The weight Alabama football carried to deliver 'Bear' Bryant's final victory

This was goodbye.

It wasn't really about Alabama vs. Illinois, even if that was the matchup featured on marquees around Memphis. It wasn't about the Liberty Bowl, even if that was the vessel. And it certainly wasn't about the players, even if that's what Paul W. "Bear" Bryant would have preferred.

This was about the Bear saying goodbye to college football, and nothing else.

The news that the 1982 Liberty Bowl would be Bryant's final game as Alabama's living-legend coach broke on Dec. 14, and it spread as fast as sports news could at a time when the internet and social media didn't exist, and when cable television was still in its infancy. Less than three weeks later, Penn State would take on Georgia in the Sugar Bowl with a national championship at stake, arguably to no more fanfare than a Liberty Bowl matchup of two 7-4 teams. Penn State's 27-23 win aired on ABC to 40 million viewers. How many watched Bryant's last game? That was hardly calculable. ESPN had broadcast rights and only 20 million subscribers at the time, but demand for the game compelled syndication in eight countries. United Press International's Frank Thorsberg described ticket availability as "about as common as gold bullion," as Liberty Bowl Memorial Stadium held just 52,000.

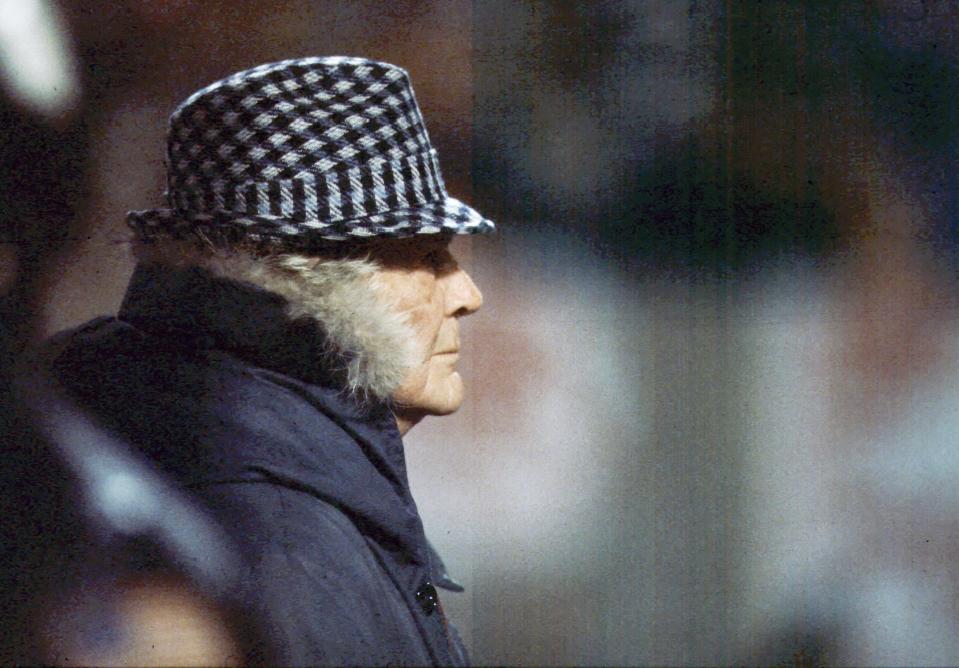

An illustration of Bryant holding his trademark houndstooth hat above his head, as if tipping it toward the entire sport as a farewell gesture, was splashed across the front page of the Memphis Commercial Appeal's preview section on the game. Halftime performers included Cybil Shepherd, Charlie Rich and Jerry Lee Lewis.

The sport would never be the same without a coach who'd won six national championships, revolutionized the sport, and wielded influence beyond measure. And even the coach knew it. Bryant didn't bother trying to downplay the significance of his decision, instead apologizing to his players for putting them in the position of representing his last walk on a sideline.

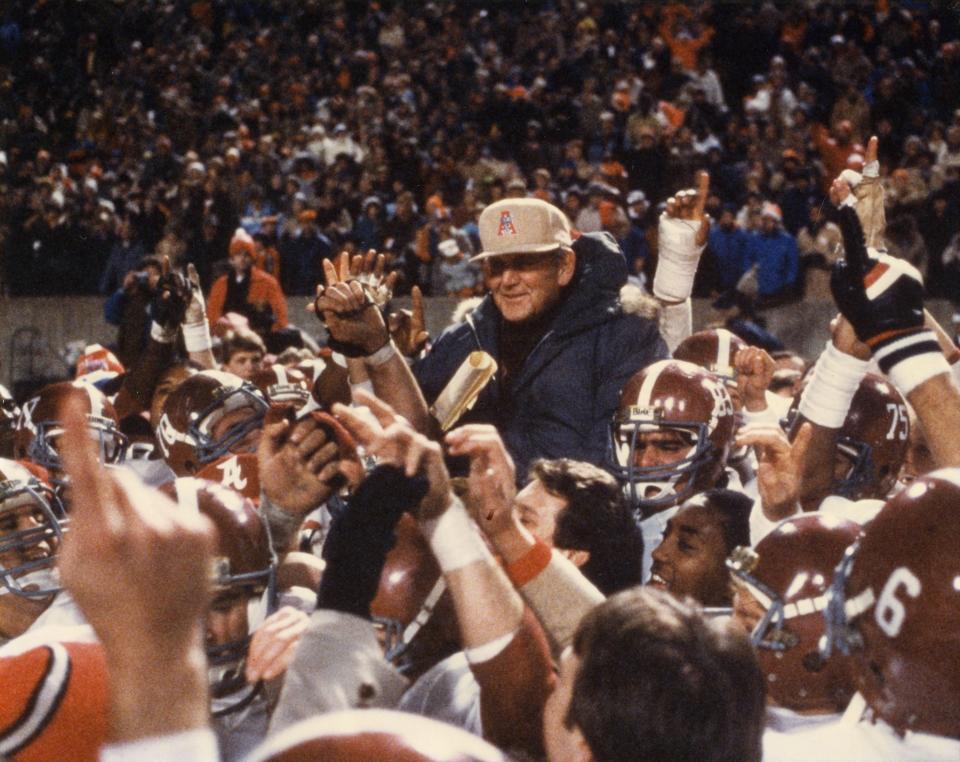

"I'm proud for winning this game, because as I told our men, whether they liked it or not, and whether I liked it or not, they would always be remembered for this game, and I'll always be remembered for this game," Bryant said after his team's 21-15 victory. "Because of the circumstances."

The Gravity

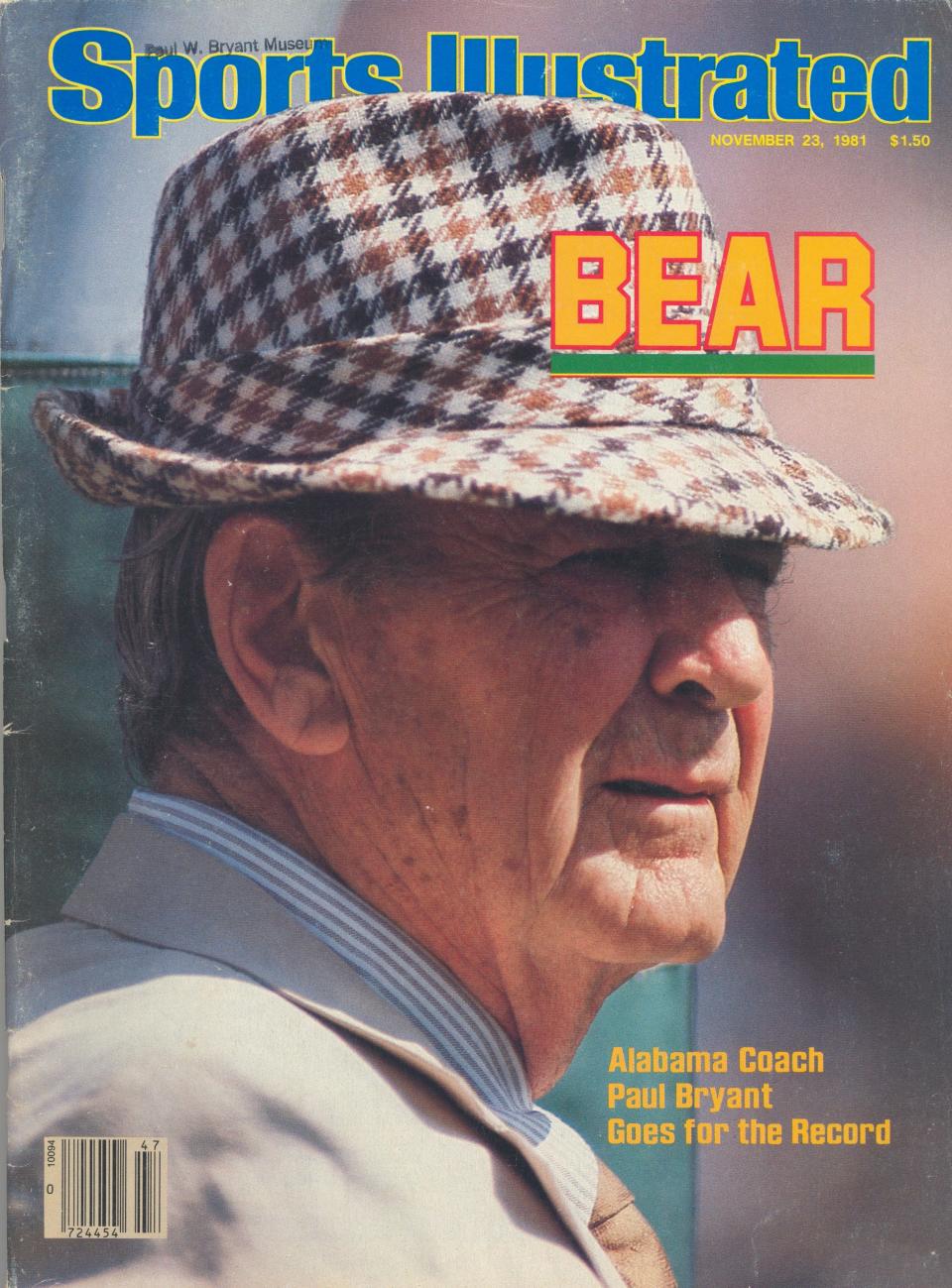

A full understanding of what Bryant's absence would mean for the sport demands a full accounting of his stature. He carried a level of clout that came not only with the success of six national titles, but also with stations in life that included being Alabama's athletics director concurrent to his coaching career. Assistant coach Gene Stallings, later to be Alabama's head coach, once took on the dual role of being the Crimson Tide's golf coach at Bryant's behest. Bryant was the 1972 president of the American Football Coaches Association. Twelve times he was named SEC Coach of the Year, and his 315th win, which came against archrival Auburn to end the 1981 season, moved him ahead of Amos Alonzo Stagg as the NCAA's winningest coach ever. Following his death, Bryant was posthumously awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President Ronald Reagan.

"More than any figure in American sports at that time, at a moment when Arnold and Jack were Arnold and Jack, at a moment when Billie Jean was Billie Jean, no single name was more iconic or as broadly recognizable as Bear, meaning you didn't have to say the last name," said Jim Lampley, who pioneered the sideline reporter role for ABC in the 1970s. "It's hard to imagine anyone having as extended an arc of influence as Bryant had."

During the Liberty Bowl practice week, some 2,000 people attended formal black-tie luncheon held at a Memphis Holiday Inn, at which Liberty Bowl founder Bud Dudley presented Bryant with a silver platter as a going-away gift. Dudley would've had to cover that platter with bars of gold to adequately compensate Bryant for the attention and economic impact his final game brought to the bowl and to Memphis. Indeed, by all accounts, it was Bryant who chose the Liberty Bowl for his final game. He'd built a long-standing relationship with Dudley since taking an Alabama team to the inaugural Liberty Bowl in Philadelphia in 1959, and had the clout to pick the venue, at least within the confines of what a 7-4 season would allow. As such, it was in essence the Liberty Bowl that received a bid from Bryant to host his farewell, not the other way around.

"I believe that to be 100% correct," said SEC Network host Paul Finebaum, then of the Birmingham Post-Herald.

Bryant's long shadow not only put Alabama in the Liberty Bowl, it cast a presence that was all the more unmistakable in its final days.

The Pressure

The shock of Bryant's retirement came from within the program and emanated outward, rippling through two generations of fans who could not recall, or at least would struggle to recall, what college football was like without him. Even his own assistant coaches were stunned by the news; linebackers coach Sylvester Croom found out no sooner than the rest of the world. Croom said he detected no signals from Bryant that the end was at hand, and doesn't believe any other assistants were sitting on a secret. Running backs coach Bruce Arians didn't get word until receiving a 3 a.m. phone call from Ray Perkins, who'd been hand-selected as Bryant's successor. Arians arrived in Memphis having just interviewed for the head coaching job at Temple and immediately sensed a level of pressure he would only feel once more in his lengthy college and NFL coaching career.

"I've only ever feared losing twice in my life. That was coach Bryant's last game, and when I took over for (cancer-stricken Colts coach) Chuck Pagano and Jim Irsay said 'We're going to beat the Packers and take a game ball to the hospital,'" Arians said. " The sense was, 'We can't lose it.' You could've cut the anxiety with a knife."

Croom, much the same, said he's never felt such a pressure to win a game as a player or coach as he did for the '82 Liberty Bowl, including Super Bowl XXIX, in which he coached San Diego Chargers running backs. Losing simply wasn't an option. Alabama had done enough of that, having ended the regular season with three consecutive losses to LSU, Southern Miss and Auburn. In an interview with Sports Illustrated just days before the game, Bryant was clear that the way the '82 season ended played a role in his decision.

"Hell yes it was the losing. Four losses is too many around here, and I'm surrounded by young alligators," he told SI, referring to younger head coaches who were using his age against him in recruiting. He would later note that his players deserved better coaching that what they'd received over the course of the season.

Sending Bryant out on a victory was paramount. And it exacted an emotional toll on those tasked with delivering it.

The Media Crush

The Liberty Bowl had neither the infrastructure nor the staff to deal with media interest that was exponentially greater than the norm. The bowl brought in former Alabama assistant athletic director Charley Thornton to help handle the onslaught of incoming reporters.

“This thing has just gotten out of hand for us," Dudley told The Commercial Appeal. "The crush of people wanting to see Coach Bryant’s last game is unbelievable and we decided we needed a real pro to handle it.”

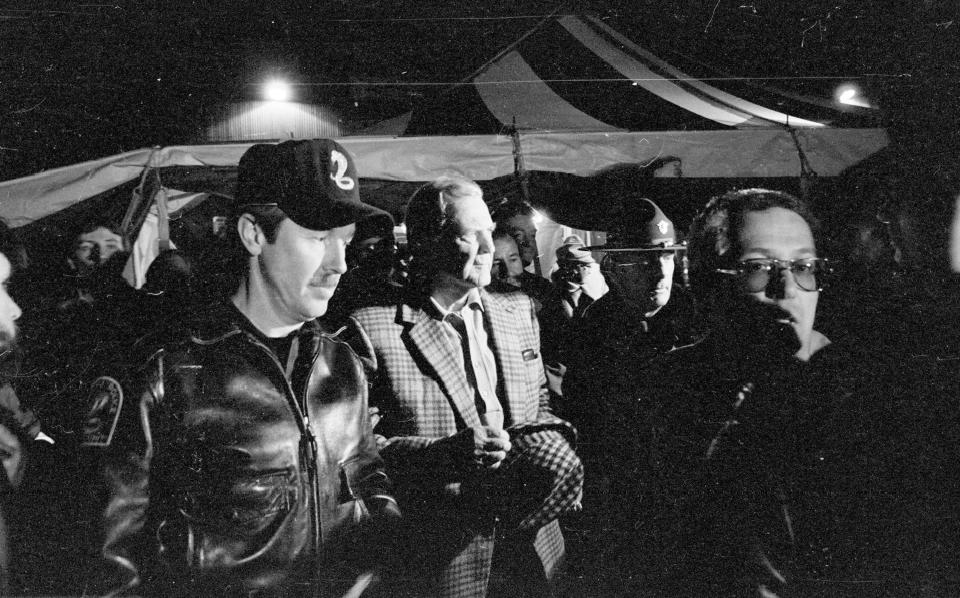

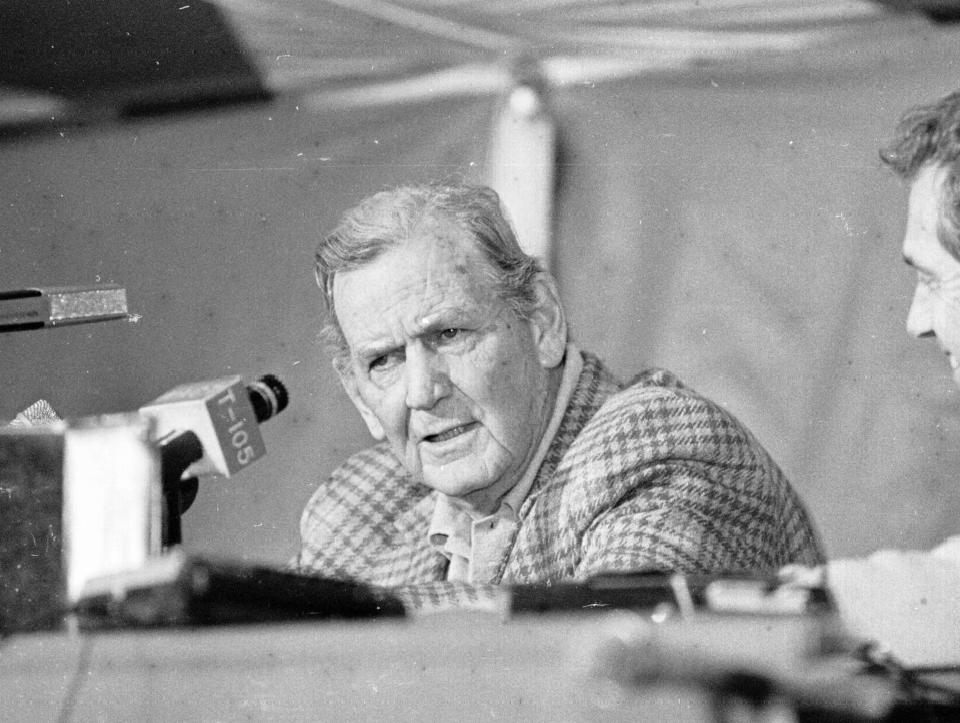

By game week, media coordinator Jack Bugbee had fielded a stunning 220 credential requests from print media alone, and auxiliary accommodations had to be made. A makeshift tent was set up outside the stadium to hold Bryant's post-game news conference.

Access was no easier for fans, as tickets sold out almost immediately after Bryant's decision was made known. Who knows how much scalpers were able to get for a pair, but the face value on a stub displayed at the Bryant Museum shows a price of just $16.

The press box was said to be every bit as packed as the stadium, and the weather made the challenge of capturing the moment even tougher. Nine people at the game, interviewed for The Tuscaloosa News' coverage of the 40th anniversary of Bryant's retirement, described the cold in extreme terms. Bitter, teeth-chattering cold. Finebaum, for one, couldn't type his story after the game because his fingers were frozen stiff. He retreated to the press box bathroom and had to run hot water on his hands to thaw them out.

"It's the biggest story of my life, and I'm having a panic attack," he said.

Deadlines, Finebaum joked, weren't enforceable for a game such as this one.

The Dejection

On the day of the game, Bryant invited a few select media to his hotel room and took a few questions about the end of his career. Finebaum, the youngest reporter in the room, asked if he'd considered stepping down a year earlier, in 1981, when the Crimson Tide went 9-1-1 in the regular season and earned a trip to the Cotton Bowl. Finebaum recalls some eye rolls around the room, but Bryant's response inferred that there were more considerations in play than his declining health, the '82 losses, or his readiness to call it a career.

"He explained that he'd put it off because there were so many people depending on him," Finebaum said. "It was a smart explanation, and one that I couldn't fully comprehend at the time."

He'd hung on, regardless. And there was a sadness about his exit that settled over Memphis throughout the practice week. A documentary film on the game, archived at the Bryant Museum, was titled "Triumph and Tears." There were plenty of those.

Kirk McMair, who had previously served in Alabama's Sports Information office, penned a letter to Bryant asking him to reconsider. Bryant thanked McNair personally for the sentiment, but assured him the time had come to pass an unpassable torch. Illinois wide receiver Mike Martin, from an outside perspective, got the impression in crossing paths with Bryant a few times during the week that he wasn't long for the role.

"He was moving slow, and not saying much. And I thought, 'This man is at his end,'" Martin said. "I didn't know that a little while after that he would pass, but you felt like he was ready to be done."

Nevertheless, Bryant remained sharp on the sideline once the game kicked off. Arians recalls Bryant's insistence on personally handling personnel decisions when it came to playing time.

"We played 66 players every game and you damned sure didn't substitute one of them. He substituted everybody. He was still a master at personnel, even at the Liberty Bowl, when he switched quarterbacks," Arians said. "My job was to have 12 running backs ready to play, but he decided who was playing. I think I argued with him once and that was enough. He said 'You coach 'em, I'll line 'em up.'"

Following the Crimson Tide's 21-15 victory, there was a sense of relief among players and assistant coaches that Bryant had gone out a winner, but it didn't manifest itself in the form of postgame joy that would be typical of a big win.

Instead, there was a pall cast over the locker room.

"There was no celebration. I was in that locker room and it was deathly silent. Everybody was crying. It was a morgue," Croom said. "It was funeral-like. It's the only winning locker room I've ever walked into and seen everyone upset. Heck, I've never walked into a losing locker room and seen it that bad."

Bryant passed away at 69, just 28 days after his final victory.

Reach Chase Goodbread at cgoodbread@gannett.com. Follow on Twitter @chasegoodbread. Nick Kelly contributed to this report.

More on 'Bear' Bryant's final game and legacy

Memphis

Alabama

Illinois

Secret

Retirement

This article originally appeared on The Tuscaloosa News: The weight Alabama football carried to deliver 'Bear' Bryant's last win