I went to the Texas-Mexico border. It isn’t as bad as you think, but it’s bad enough | Opinion

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

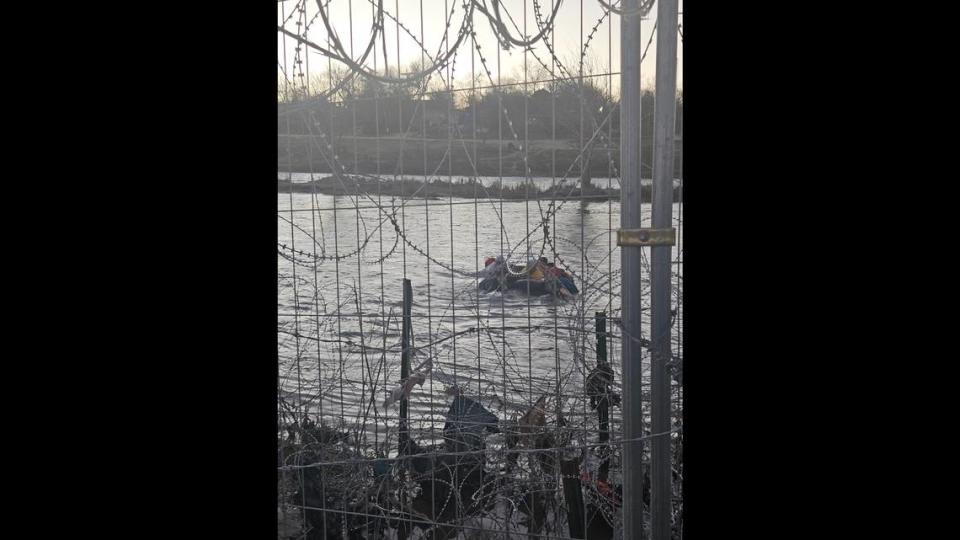

It’s hard to see at first, but as the winter sun sets on the border between Mexico and Texas, it becomes clear that five young people are floating on a black raft in the middle of the Rio Grande, underneath a port of entry in Eagle Pass, a prominent spot for legal and illegal crossings. A horse grazes on the sparse banks of Mexico behind them, unaware of their struggle. The migrants on the raft, ranging from approximately 17 to 25 years old, traverse the current in the cold water, taking them at least 50 yards downstream from where they began.

After several minutes of effort and chaos, they reach the banks of America, land of liberty and promise — but they still must step their soaked feet on the soil. This part of the Texas/Mexico border is heavily fortified with concertina and razor wire — the former isn’t as sharp as the latter — stacked on top of each other, intertwining like giant silver Slinkys and into a metal fence. But none of this is fun. Not for the young people, shaking and cold now, not for the Texas National Guard members who await them on dry ground— also about the same age, dedicated to the preservation of law and security — not for the rest of us watching the story unfold like a bittersweet film.

This is rare now, thanks to the razor and concertina wire — set atop shipping containers in some spots — that the Texas National Guard has placed. Gov. Greg Abbott directed the placement along this lengthy stretch of the Rio Grande, sparking a legal clash that has already reached the Supreme Court. The efforts have made the border here nearly impenetrable. Even though Eagle Pass was once an epicenter of record-high migrant crossings, as recently as December. Even though it’s also caused an uproar with the Biden Administration.

Migrant crossings in this area have dropped from over 10,000 one December day to about 200 per day recently. In all, U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) had almost 250,000 migrant encounters in December, a record high. Conservatives will say the Texas border crisis, built on months and years of state-federal conflict, is both a humanitarian crisis — in terms of human trafficking and smuggling — and an issue of law and order. Liberals will argue that by adding wire along the border, Abbott is usurping federal power and using cruel, inhumane tactics to keep out immigrants who are trying to claim asylum.

Immigration is a cornerstone of America’s foundation. However, after seeing the border first hand, it’s clear that much of the story of the modern border is cherry-picked to highlight the news of the moment. Rarely does it show a cohesive picture that explains why there’s wire along the border in the first place, why anyone would bother trying to cross anywhere other than a port of entry, and how laws are being enforced differently than they were a few years ago.

The border is nothing like what you think it is: In some ways, it’s worse; but in some ways, things are getting better.

What the border looks like right now

On a mild, sunny February day at the border, things are unusually calm. There is little activity on the ground beyond a nonstop line of traffic on the bridges to ports of entry. It looks nothing like it did in December, when over 10,000 migrants moved through Eagle Pass in one day. Video footage and photos during that month showed swaths of young men in Shelby Park, underneath one of the bridges where Border Patrol had set up a processing center to process unlawful entries, despite the fact that a legal port of entry was above them.

In a lengthy ride-along with Lt. Christopher Olivarez, a spokesman for the Texas Department of Public Safety in the South Texas region, we encountered just three small groups of people trying to illegally breach the fenced border. Two of the groups each included two small children. One group struggled to actually get through the fencing and stood on the other side of it, occasionally pleading with DPS troopers and National Guard troops for help.

January and February tend to be lower months anyway for migrant crossings. For the Texas National Guard, DPS, and even CBP, a less active border is not a miracle, nor does it double as a political statement of defiance, even though it’s been labeled as such. It’s proof that Abbott’s directives, for the National Guard to take over Shelby Pass and to continue to lay wire, are succeeding.

In fact, contrary to reports that Abbott has ordered more wire in defiance of the recent Supreme Court order, members of the CBP have never cut the wire. Abbott has defied nothing; the order never mentioned additional fortification.

“So there was no standoff between Border Patrol and the National Guard about the wire?” I asked Olivarez as we drove slowly along the border, since the Supreme Court order thrust Texas into the national spotlight again. He shook his head.

Olivarez dismisses insinuations that Border Patrol and the Texas National Guard are at odds or perform opposing missions as misleading. He maintains both have similar goals — to maintain law and order — even if they’re accomplished in different ways.

The immigration process, then and now

Under federal law, it’s a crime for a noncitizen to enter the U.S. anywhere other than a port of entry. The Biden and Trump administrations have handled illegal entry differently.

The Trump administration instituted several policies that limited overall migrant encounters, such as Title 42, Remain in Mexico, building more wall segments, opposing automatic release into the U.S. of some migrants who are apprehended, and more. When Joe Biden took office, there were fewer illegal border crossings and migrants applying for asylum since about 1975. Aside from a spike in 2019, during Donald Trump’s presidency, the numbers hovered around 300,000 every year.

In 2021, Biden made several executive policy changes that immediately changed enforcement of federal immigration law. These include ending border wall construction and announcing that some who were caught entering illegally would not be initially deported. These policies contributed to a surge of migrants at Texas’ border.

In 2023, federal agents encountered nearly 2.5 million migrants at the Texas border — including migrants who requested asylum at ports of entry — breaking the previous year’s record. It’s a staggering increase from the 24-month period in 2019 and 2020, when about 1 million migrants were encountered.

Texas takes control

To understand how we got here, you could go back to the beginning of the Biden administration, but July 2023 will do. There are private properties along the Texas border, just like any other state. The state of Texas had gotten consent from the owners to arrest migrants trying to cross illegally on such land.

“We were arresting single men and single women,” Olivarez said. “We still call Border Patrol. They show up. They would take them to another area away from here, and they would process them somewhere else that was working. It was somewhat manageable.”

In August 2023, Eagle Pass City Council rescinded an agreement that let DPS enforce criminal trespass laws in the park.

DPS officials say that word spread in Mexico and elsewhere that migrants would not be arrested. Border Patrol officials slowly moved in to handle the growing numbers and set up a processing center underneath the port of entry. The numbers ballooned to more than 10,000 in one day in December. In January, Abbott directed the Texas National Guard to take over Shelby Park again, this time against the city’s wishes.

Physical remnants of the December surge remain: In July, when the National Guard first controlled Shelby Park, the area was clean. But migrants would remove wet clothes, use them as protection to push down the sharp wire and then leave them behind. They’re still there, a visual reminder of what happens when lawlessness meets desperation.

The future of the border crisis

At least on this Sunday afternoon, there was little presence of Border Patrol, in part because the National Guard’s presence lets the federal officers move on to other pressing matters. But there’s still conflict. Not between DPS or the Texas National Guard and Border Patrol, but between their objectives and Biden’s aims. This is most recently seen in the border bill Biden is trying to push through Congress.

U.S. Border Patrol Chief Jason Owens told Fox News on Feb. 7 he is “disappointed” in Congress for failing to pass a border deal. “We are languishing in the same situation,” he said. “The mission of the Border Patrol is not to process asylum seekers.”

Owens said a bipartisan Senate compromise, rejected by Republicans, would have added more agents, technology and infrastructure. Conservatives who wanted tougher enforcement measures say Biden has executive power to enforce current law and that the legislation would allow too many people to enter the country.

The border is neither as secure as it should be nor as chaotic as it’s been. Seeing migrants crawling through porous spots is at once heartbreaking and aggravating. You find yourself thinking: This is our country, you can’t just break the law coming here. Yet you also think: These people are shaking and cold, forging across the Rio Grande. Look what people are willing to do to make it to America.

A Guard member tells the crossers, in Spanish, that they’ll be arrested for criminal trespassing if they continue to try to breach the carefully placed fencing. They are encouraged instead to make their way to the legal port of entry above them, where they will simply be processed by Border Patrol and released into Eagle Pass, like almost everyone else is these days.

An arrest will make an asylum claim much more difficult, but it’s not clear if they realize this. They simply walk another 25 feet upstream and try again to shimmy through the barricade. Again, the Guard informs them they will be arrested for criminal trespassing — including a 17-year-old, who would be prosecuted as an adult.

Even so, the migrants trickle across. The second group we encountered included an older migrant from Colombia and two small children, about ages 8 and 10. The man said they were his children, but border officials have no way to check. The children crawled through a gap in the wire first and he followed, with difficulty.

We asked why he and the children dared to swim across the Rio Grande, even with its strong current, rather than simply cross via the port of entry, he repeated that they had to cross there. Without fear of frigid waters, arrest or failure, and with only a gallon-size plastic bag of belongings to their names, he explained: They were on their way to New York to find a different life.

Do you have an opinion on this topic? Tell us!

We love to hear from Texans with opinions on the news — and to publish those views in the Opinion section.

• Letters should be no more than 150 words.

• Writers should submit letters only once every 30 days.

• Include your name, address (including city of residence), phone number and email address, so we can contact you if we have questions.

You can submit a letter to the editor two ways:

• Email letters@star-telegram.com (preferred).

• Fill out this online form.

Please note: Letters will be edited for style and clarity. Publication is not guaranteed. The best letters are focused on one topic.