What if we were already living in Octavia Butler's 'Parable of the Sower'?

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

This story is part of Image issue 11, “Renovation,” where we explore the architecture of everyday life — and what it would look like to tear it all down. Read the whole issue here.

What face comes to mind when people think of the term “American artist”? Whose stories?

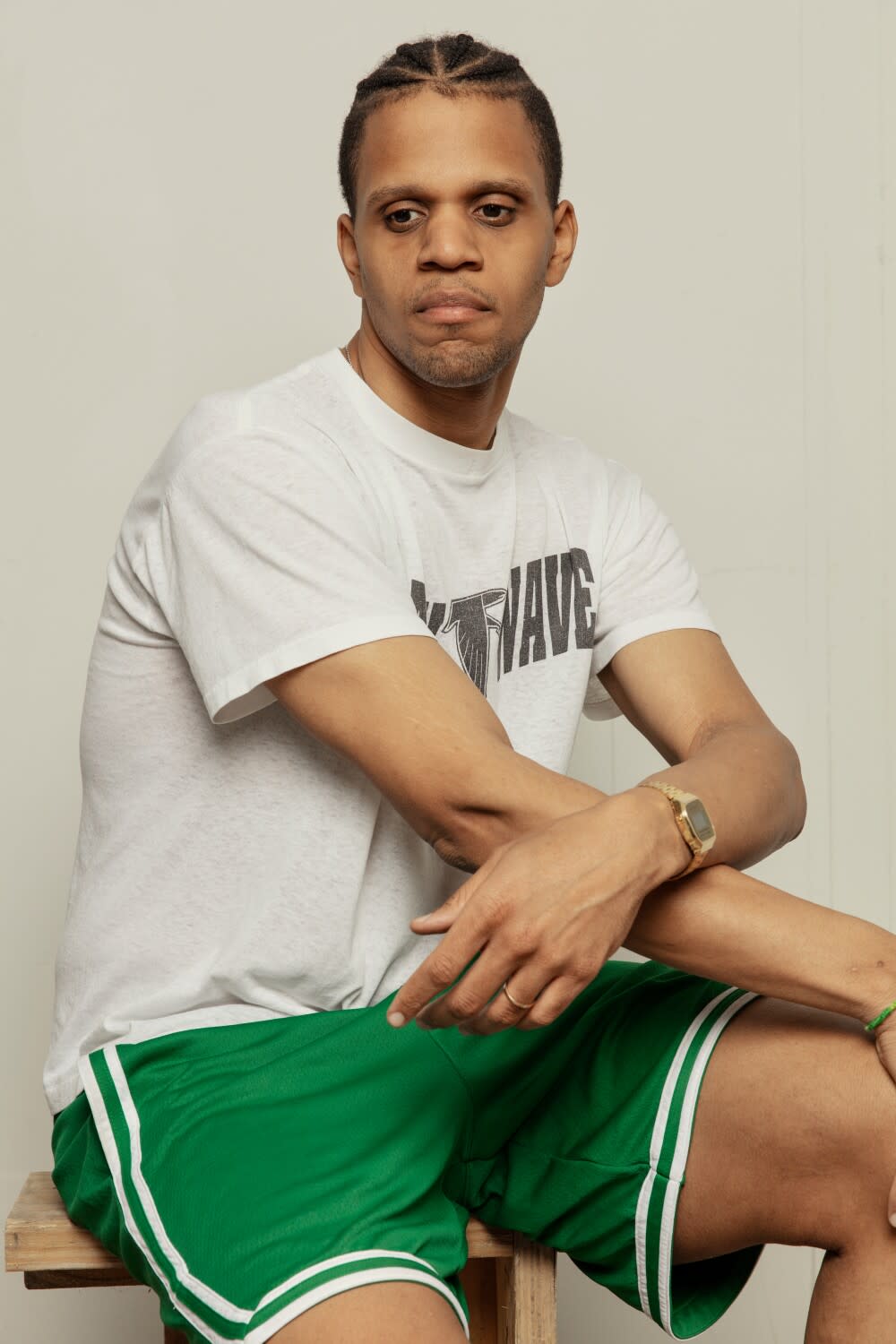

The 32-year-old visual artist who took the name American Artist knows that they are not the picture that comes to mind: “I am a little bit of a troll in terms of how I engage with public perceptions of what it means to be an American artist.” The renaming was also a way of stepping into the role. “I was making art, but I didn't really know how to create a life for myself around that, professionally and otherwise. And so, part of it was: What if I just say I am that, then would that make it true?”

The renaming unlocked a new focus in their art that also closely coincided with their discovery of the speculative fiction of the Afrofuturism pioneer Octavia E. Butler.

Dystopia. History. Conservation. Memory.

American Artist’s admiration for Butler’s work has led to their creation of the upcoming “Shaper of God” exhibition, which opens on May 28 at REDCAT in downtown Los Angeles. A collaboration with Pasadena’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory and the LACMA Art + Technology Lab, the exhibition is a conversation between two very different artists — both of whom lived in Pasadena and attended John Muir High School during very different eras.

In Butler’s novel “Parable of the Sower,” a teenage Black girl named Lauren Olamina becomes an unlikely leader after her gated and fortified community — the fictitious Robledo — is attacked and burned. She must cling to her own philosophy, which she calls Earthseed, to lead displaced survivors toward a better life.

The most famous Earthseed parable: “The only lasting truth is Change.”

Fittingly, American Artist’s exhibition is like a road map through Southern California locales inspired by “Parable of the Sower.”

The fallen wall of Robledo. The vintage bus stops of Butler’s life. Butler’s journal entries.

In this conversation, I talk to American Artist about the imprint of a childhood near JPL, Butler's inspiration and building a better future.

Tananarive Due: You grew up in Altadena. What are some of the personally iconic spaces or buildings that come to mind for you when you think about where you grew up?

American Artist: The one that really came to mind, and I think it was really key for me in developing this project, “Shaper of God,” was the site of this JPL campus that exists right on the perimeter of Altadena and La Cañada Flintridge. When I was young, I would drive by it with my family, and then eventually, when I was driving to high school, John Muir High School, I would drive from Altadena towards the west, and then I would turn south, right on where it overlooks JPL. And it was always this strange, almost sci-fi-ish site, because it's this extremely advanced space institute that's sitting in this canyon, that's kind of on its own, and it's surrounded by these suburbs. It felt like something out of a movie. It wasn't a site that I was ever able to visit when I was that age, so it also had this kind of curiosity about it. And thinking of other institutions like Caltech or PCC [Pasadena City College] — these institutions that have this culture of academic prestige — I think they really informed the culture of Pasadena and Altadena.

TD: I'm wondering how included you felt in that culture.

AA: I didn't necessarily feel included. I felt like they created this image of what aspiration was meant to look like. I was a creative kid, I liked creating art, but I was also interested in science and technology. And at one point, I imagined the possibility of going to Caltech, but at the same time it seemed elusive to me. But knowing that was there informed my image of what I should aspire to, what I should try to accomplish.

TD: Let's talk a little bit about Octavia Butler. What are the biggest ways you would say that her vision dovetails with yours?

AA: Octavia Butler was very understanding of the ways in which power operates and how it impacts people differentially. I think also understanding the way that apocalypse is not a singular event but something that we are living in. What I relate to is wanting to speak about these systems that often oppress many people that encounter them, but not in a way that treats it as something spectacular, but rather something that we're continually navigating. Octavia Butler understood that because she had a very difficult life herself.

TD: All of Octavia’s readers have an origin story. I'll tell you mine. It was in the mid-1990s, and I was working on my novel “My Soul to Keep,” about an immortal African from Ethiopia. I was talking about it with a friend of mine who was like, have you ever read Octavia Butler's novel about an immortal African? And I had a complete panic attack — I had to run out right away to get “Wild Seed,” more out of a sense of terror that I might be duplicating a book. But, of course, “Wild Seed” was nothing like my book. And then it was joy and wonder — I'd been introduced to this revolutionary writer that I would soon meet and come to know and love dearly, both personally and as a reader. What was your first Octavia Butler novel, and what was the impact on you?

AA: The first novel that I read was “Dawn.” A friend recommended it to me. We were speaking about some of the most radical ideas we'd encountered in fiction. I think this idea of aliens wanting to regenerate with humans — it wasn't like an invasion, it was like, "Hey, we picked you up, and you're hanging out with us." I think that really stuck with me.

TD: When my husband, Steven Barnes, and I talked to Octavia in 2000 — Octavia had known him for quite some time — we asked her about her vision and how she was using her art to try to create what I call real-life world building. And she mentioned “Dawn” specifically and “Parable of the Sower” specifically. “Dawn” was her way of like, OK, we're really headed to ruin, and we need aliens to come step in and set us on the path. But in “Parable of the Sower” she wanted to do the same thing but with religion.

For Southern Californians, it's particularly disturbing to read “Parable of the Sower,” which is the subject of your exhibition. Not just because the year when it’s set is so rapidly approaching — and really, it already feels so much like here and now — but it's the familiarity of the spaces that we can all imagine. Robledo, this fictitious gated community where the protagonist Lauren Olamina is living with her family and other families, that they hope will be a sanctuary as the world is falling apart around them. The drought conversations feel very personal, the fires feel very personal. Why did “Parable of the Sower” speak to you so deeply that you're creating the physical wall from Robledo?

AA: This wall was important to me because it feels so Californian and so much of what's described in the novel feels quintessentially Californian, the way wealth distribution becomes so clear within the landscape of Los Angeles. I did think about the wall as the symbol of that division. In the case of Robledo, every single community has its own wall; there are different scales of walls based on how much money they have, and how much they fear invasion. And that, to me, felt like taking this thing that was very real about Los Angeles and just kind of escalating it.

TD: I find it so fascinating that you're re-creating the Yannis window. For readers who don't know what that is, it's a big piece of technology, like a big smart TV, that is basically the sole entertainment for this community. You created a short film representing the kind of newsreel that the Robledo community might have been watching. What's the significance of this in your exhibition?

AA: This film seems to be something that Robledo created at a point when they were wealthy and things maybe hadn't hit rock bottom. The video supposedly is created by the Robledo Historical Society. And, interestingly enough, it's not a tour of Robledo — it's actually a nature tour of the Arroyo Seco Canyon, which is this area that sits between Altadena, Pasadena and La Cañada Flintridge, and so it's pretty close in proximity to where Butler lived and grew up. It's also where Jet Propulsion Laboratory exists. It also shares a close border with John Muir High School, where Butler went. And so, to me that area represents many historical moments and the conflation of different realities. It appears to be this nature tour of the site, but it's fictional and it's speculative.

TD: Octavia did not drive (my husband often drove her places). That aspect of her life is also addressed in your exhibition with the representation of the bus stops. Why was that important for you to include?

AA: I wanted to put these bus stops that are based on Los Angeles bus stops that Butler would have sat at, routes she would have taken. One of the bus stop signs resembles how they would have looked in the 1960s and another one resembles how they would have looked in the 1980s. It's a way of not only conflating space — like the real landscape of Los Angeles with a fictional landscape of Robledo — but also the sense of time, because you don't really know what time period you're existing in.

TD: I'm thinking about how you named yourself to pull something out of yourself and how that really did help remake you. It worked out incredibly well. It also worked out incredibly well for Octavia Butler. It's very fitting that you have notes from Octavia Butler's journal as a part of this exhibition. Some of her quotes have become memes — “so be it, see to it” comes to mind — but these pep talks that Octavia gave herself often were in opposition to the forces that were trying to hold her back. Listen, Octavia Butler died in 2006; she finally got on the New York Times bestseller list with “Parable of the Sower” in 2020, during the pandemic, so she's really working against every force against her, and these forces have been against her since she was a young Black child growing up in poverty. I would love to ask you what stands out for you about the journal excerpts you've chosen for this exhibition.

AA: I wanted to find ways to show Octavia Butler as a descendant of Black people that had migrated to Los Angeles. Her mother moved from Louisiana and was working as a cleaner in white people's homes while Octavia Butler was growing up. Some of the materials are letters that her mother wrote to her about what it was like to grow up in Louisiana, where there are no schools for Black people, there are only dirt roads. One letter describes that situation and is juxtaposed with this bus map that Octavia Butler carried. So, kind of trying to show this progression over time of what Octavia Butler was able to have and achieve relative to her family.

TD: I recently taught “Parable of the Sower” in my Afrofuturism class at UCLA and asked my students to create their own Earthseed community — really just a description of a community. If you were creating an Earthseed community, what would it look like and who would those members be? What are you seeking shelter from?

AA: One thing that I think about seeking shelter from, which hasn't really been possible for me, is from institutional obligation. From having to align myself with institutions that I feel are compromising my values. Being able to create a community that would be autonomous for itself, which seems under capitalism really unrealistic, but it's something to think about. As far as who I would want to collaborate with, people that are creative and inspiring and nice. People that are interested in creating a world that feels equal.

Tananarive Due teaches Afrofuturism and Black horror at UCLA. She is an American Book Award-winning author who was an executive producer on Shudder’s "Horror Noire: A History of Black Horror."

More stories from Image

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.