‘When we were growing up, it was wonderful’: Life before the Innerbelt

Since moving into a balcony apartment on Vernon Odom Boulevard, life’s been easier these past two years for Norris Hill, who gets around in a wheelchair. Like others from the old neighborhood, Norris still calls it Wooster Avenue when his mind travels back 60 years to his childhood in Akron.

“When we were growing up, it was wonderful,” said his wife, Cheryl Hill. “You could leave your doors open. People looked out for you. You could sit on the porch. You could walk across the street at night. It was a wonderful time.

“We had Isaly’s. We had Rockefeller bakery. There was a pool room. And there was a record shop,” she said.

“It was called Homell Calhoun record shop,” Norris recalled. “It was nice. I’m telling you. You couldn’t believe how nice."

“Everyone kept up their yards,” Cheryl remembered.

“We had all the business up there. And I watched it all fall apart when urban renewal came through,” Norris said.

History has placed another fork in the road for the former Lane-Wooster neighborhood, now called Sherbondy Hill.

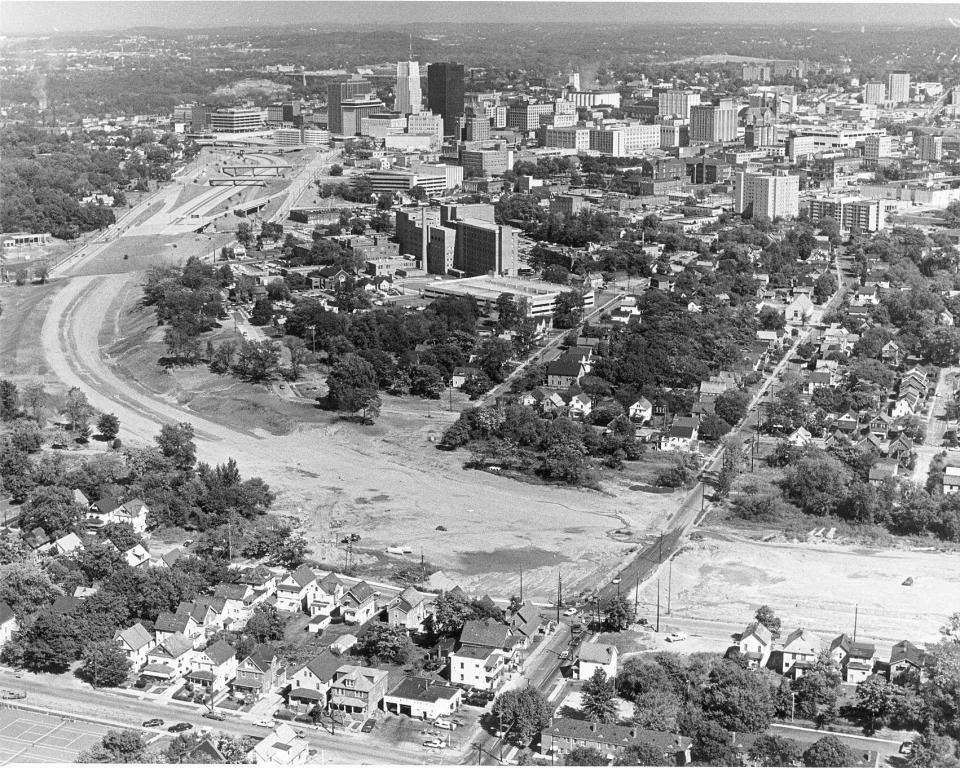

The city, this time, is inviting residents to help write the next chapter nearly six decades since the Innerbelt project. The highway ran over budget, fell short of projected traffic volume and never reached Route 8 as intended. But it saved a couple of minutes for suburban commuters heading downtown — at the cost of demolishing hundreds of homes and dozens of businesses, almost all owned by Black people.

The highway was part of U.S. urban renewal programs of the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s. The answer to "urban decay" displaced thousands of mostly lower-income residents in Akron, leveling their homes, cleaving neighborhoods in half, scattering families and separating communities from economic opportunities.

At a reunion hosted by the Akron Urban League and other community partners Aug. 28, the Hills joined dozens of current and former residents who shared joyful memories, unresolved frustrations and hope for the future.

The state has given the city 30 acres of the decommissioned highway north of Exchange Street. And city leaders, in learning from the mistakes of their predecessors, are welcoming resident input in the redevelopment plan.

The Akron Innerbelt:The failed Innerbelt drove decades of racial inequity. Can the damage be repaired?

But many who attended the event last month said future generations must understand what was lost if the community is to rebuild it, together, in a lasting and equitable way. This, from the mouths of some of those who lived there, is the story of a community of promise — a village, many called it — buried by the Akron Innerbelt.

Back in the old neighborhood

Cheryl Hill’s relatives landed in East Akron from Alabama before her parents bought a house at Mallison and Euclid avenues. World War II was winding down and the Akron Zoo wouldn't officially open for another decade.

Norris Hill, her future husband, grew up three blocks west on Euclid Avenue with his father, a union rep at Firestone who migrated from Texas, and his mother, who also was from Alabama.

The family had already left its mark on Akron. Cheryl’s grandfather, George Suddeth, started Arlington Church of God, and her uncle, “Big John” Suddieth, was the first Black police officer in Akron.

Cheryl, who worked at an office building on Market Street, and Norris, who retired after 34 years in building maintenance at the University of Akron, raised their children on Delia Avenue in nearby West Akron. They moved back to the old neighborhood two years ago into an apartment on Vernon Odom Boulevard. Cheryl's childhood home near the zoo was torn down. The home where Norris grew up is now rental property, still standing beside Perkins Park.

"A lot of people thought, 'Why are you moving back in the neighborhood?' We live right over there," Cheryl said, pointing to the four-story apartment building across the street from the Akron Urban League and Helen Arnold Community Learning Center. "We've never had any trouble there."

But life on what was once Wooster Avenue is nothing like it was before. Businesses are clawing their way back, but the economic landmarks of Akron's premier Black community are long gone. Urban renewal destabilized the area.

“And the riots messed it up in 1968. A lot of people scattered after the riots,” said Cheryl, who came home from classes at UA one day to the full-blown, racially charged conflict in her neighborhood.

“We sat on our park porch, watching the National Guard walk around, like wow,” Cheryl said.

‘The two Americas’ in Akron

Cities burned after the 1968 assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy. In Akron, rioting on Wooster Avenue came years into the city's use of eminent domain to uproot hundreds of families in the path of the Innerbelt project.

The 1969 Akron Commission on Civil Disorders, which probed the causes of the riots, found that Black Akron had for decades been systematically cut off from housing, educational and economic opportunity. Decades later, those same disparities lingered, according to the 2018 Elevate Akron report by the Brookings Institution and the Greater Akron Chamber.

Black voters and residents in 1969 simultaneously supported police in the pursuit of preventing crime but could not tolerate discriminatory policing. Signs of governmental neglect included, among other things, city trash trucks visiting their curbs less often than in white neighborhoods.

"[D]iscrimination is legally, morally, politically, and socially intolerable and indefensible, and if it is eliminated, the black man can live his life in accordance with his abilities and desires as every American should," the report stated.

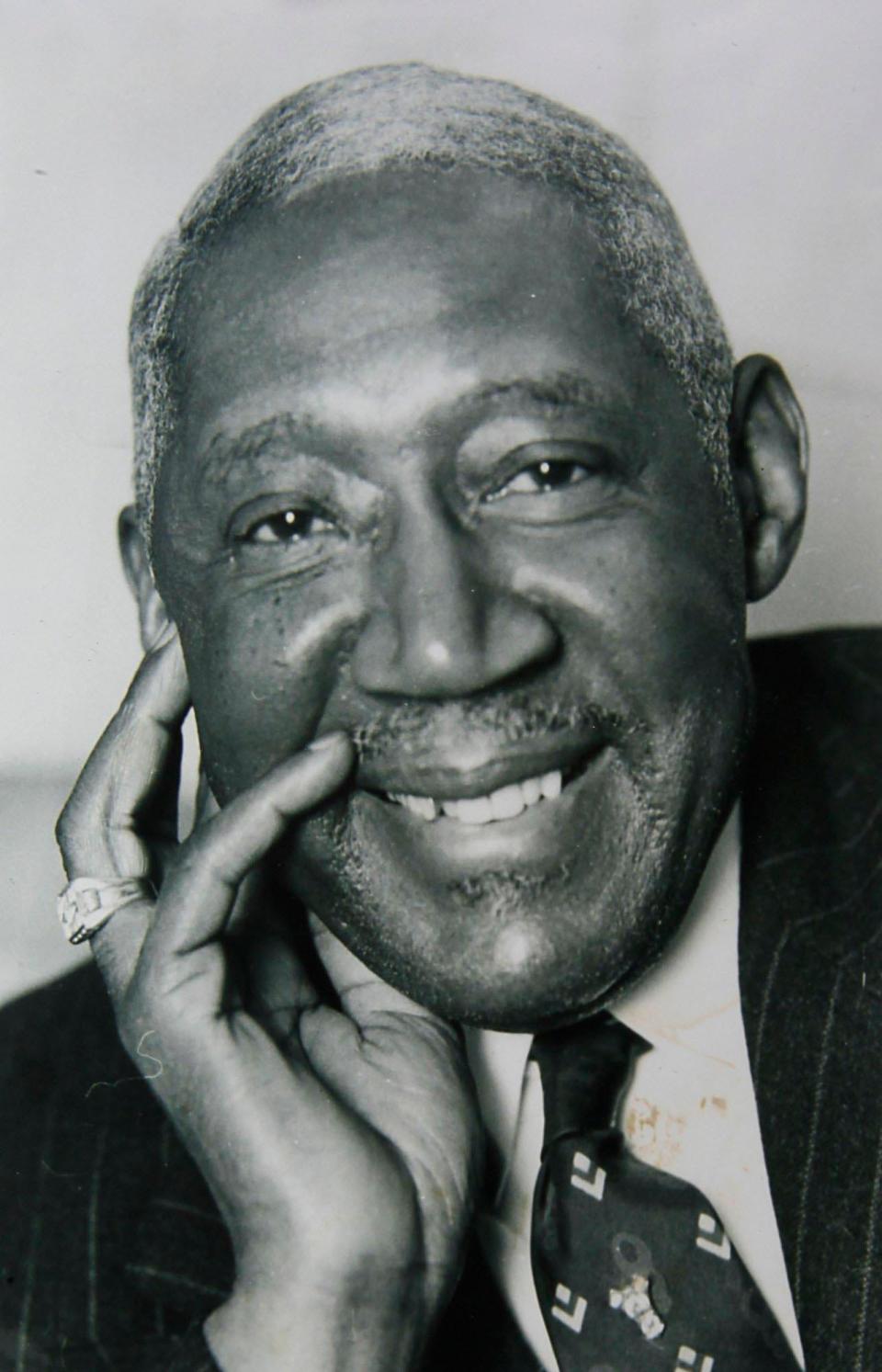

Ted Thompson was about 16 when the report was published. He'd grown up in a one-bedroom apartment with his single mother on Moon Street, about halfway between the Hills' childhood homes.

“I was starting to become politically aware. You know, by 18, I was probably fully engaged in political action,” said Thompson, who later lived in St. Louis and Durham, North Carolina, after studying at UA to become a clinical laboratory scientist.

“The big [social cause] of the day was racial equality,” Thompson said. "Police injustice existed then. But the overall was racial equality and the inequality of the two Americas.”

Thompson eventually moved back to Akron, where he advocated for police and other reforms as president of the Coalition for a Safer Community. He now cares for his aging mother in a four-bedroom house in the Summit Lake neighborhood.

‘You got to go somewhere else’

Raised by a supportive mother and community, Thompson believed there was something other than graduating high school on a Friday and working the rubber factories the next Monday. He never knew he was poor while growing up on Moon Street until he went off to college and saw life beyond his neighborhood.

He’d attended South High School, which covered most of the old Lane-Wooster neighborhood upended by the Innerbelt project in the 1960s and 1970s. While some in the neighborhood recalled white neighbors, mostly Black families remained by the end of the time Thompson graduated high school in 1970 with hundreds of classmates, only 10 or so of them white.

White flight in the neighborhood, among the most segregated today, accelerated as the city pushed people out, offering less than their homes were worth, while bulldozing some of Akron’s oldest Black-owned businesses.

It wasn't the first time Black entrepreneurs in Akron were pushed aside in the name of progress.

Years earlier, they'd been shoved off Howard Street, Akron’s cultural center for arts and entertainment in the Black community. Entrepreneurs like George Mathews, who founded a barbershop and hotel featured in the Green Book of safe places for traveling Black people to stay in America, thrived in a district where the likes of Ella Fitzgerald and Louis Armstrong could be heard at clubs like the Green Turtle, the Cosmopolitan, the High Hat and Benny Rivers'.

“Howard Street was the social and economic hub of Akron for Black people at the time,” Thompson said of the era before it was targeted for urban renewal in 1960. “And the city came along and decided they wanted that property on Howard Street. So, one by one, they went to all of those Black-owned businesses and said, ‘You got to go somewhere else.’ ”

“So, that's how Wooster Avenue became the economic and social hub,” Thompson said.

He remembered how Sistrunk’s Serve All Barbershop and other businesses originally located on Howard Street appeared on Wooster Avenue in the late 1950s and early 1960s, only to be razed by the Innerbelt project a decade later. Thomas M. Sistrunk Jr., who left Alabama to run the barbershop in Akron where he led the community as a civil rights activist, writer, speaker and poet, died in 2017.

Life on Wooster Avenue

Invited to share his memories of the old neighborhood at the Innerbelt Reunion last month, Thompson spoke of a village where Black lawyers, doctors, factory workers, nurses and business owners commingled. The people provided for themselves and cared for each other.

“Let’s be real,” he added. “Our community was not some pie-in-the-sky utopia. But even those who had an illegal hustle respected and looked out for the elderly in the community because they knew the life lessons being taught were positive — even if they chose to ignore them.”

Thompson walked with neighbors to the stores at Raymond Street and Wooster Avenue, past record shop speakers playing the proud, soulful beats of Curtis Mayfield, James Brown and Sly & The Family Stone. As a boy, he’d peek inside the Hi-De-Ho Lounge, chancing a glimpse of adulthood while grabbing a to-go order of Thalia "Heavy Duty" Dawkins' famous shrimp.

He spent his teenage years at the custard stand at Edgewood and Euclid. He bent his young ears to the politics of the day at barbershops and gas stations owned by Black men and women.

“The construction of the Innerbelt aided in the destruction of this vibrant community. But what can we learn from this disastrous history?” Thompson asked the crowd that gathered to reflect on the past and plan a better future. "Abandoning our community for someone else’s, while short term it may financially benefit the individual, long term it deprives us as a community of our cultural, social, moral, economic, spiritual and political power.”

From the Deep South

As Thompson spoke, Bertina King leaned into an oversized print of an old black-and-white photo zip-tied to a chain-link fence outside the Akron Urban League. Her grandfather lived on Euclid, right in front of the zoo, and owned a gas station and towing business at Wooster and Moon.

King, an Akron police detective nearing retirement, grew up in one of the 145 public housing units in the original Edgewood projects, which were replaced in 2008 by the federally funded construction of Edgewood Village. Her family was part of the Great Migration that brought Black families, sometimes a few at a time, away from the Jim Crow South to Akron and other booming industrial cities up north for work in rubber and automobile plants.

“Like most of these people will tell you, they're from Alabama,” just outside Birmingham, King said. “Talladega, that's where my mom was from. And then my mom met my dad. When my dad was killed when I was like 3 or 4, that's when we moved into Edgewood.

“But it wasn’t like bad projects; it was like home.”

King would pack a sandwich and run out the back door of her grandfather’s house to get lost with other children for six or seven hours in the acres of woods around the zoo, which they also frequented. They bounced between the Ed Davis Center and Perkins Park, where the older kids would hang out, or ride their bicycles all the way up North Hill.

“You could walk everywhere and do everything,” King said.

“We would go to Crouse School in Perkins Park, and they would have events all day long. We’d go up there at 8 o’clock in the morning. My mom didn't worry about us. They’d give you breakfast. They’d teach you how to play games. And then you’d come home, get your swimsuit on and go to Perkins Park and swam. If you didn't know how to swim, they taught you. Then you come back, change and go back up to Crouse School,” said King, who lived up the hill on Glenn Street.

Then the kids would all race home, praying they crossed the threshold of their homes before the streetlights lit up at sundown. It didn’t matter whose kid you were. On the street at dark, the community kept its own in line.

“We had to be home when the lights came on,” Barbara Richardson said. “In the house."

Families scatter, schools close

Richardson lived on Euclid Avenue until 1967 when she turned 18.

Every school she attended is gone. While Crouse was rebuilt, most of the schools that anchored the Lane-Wooster neighborhood no longer exist.

Howe School closed in 1972. Grace Elementary was decommissioned in 1977. West Junior High had closed in 1953, and Thornton Junior High School was demolished after the 1979 school year and sold to the city as part of the Opportunity Park urban renewal project. The property is now an Aldi grocery store. South High School, built in 1956, was open only 24 years before closing and, eventually, reopening as Miller South School for the Visual and Performing Arts, which some now want moved to Kenmore.

There were so many kids before urban renewal, Richardson remembered. She rented a home on Rhodes Avenue near the Innerbelt project. After her husband got out of the service, they moved out to buy their own home and the Rhodes Avenue apartment house was torn down the next year.

Her mother and father moved to a house on Orlando Avenue in 1967 and rented out their old home on Euclid Avenue — at an address that, today, is a bridge over the Innerbelt. The city compensated the family for taking the home and land through eminent domain.

“I don't think they was offering too much,” Richardson said of the city program to buy and bulldoze a path for the Innerbelt. “To be honest with you, I couldn’t tell you what it was. I just know it wasn’t what it should have been. And I heard them talking about that.”

‘A farm in the heart of the city’

Phillip Gibson moved with his mother to his grandmother’s house off Livingston Street when he was almost old enough for kindergarten. Seven years later, the adults at home started talking about a highway cutting through their secluded property with a big garden.

“It was kind of like being on a farm in the heart of the city,” Gibson said, sharing fond memories of the property eventually seized by the government.

His mother, who died a couple of years ago, tried to persuade his grandmother not to take a house on Wildwood Avenue in West Akron, in an area where Gibson said many families displaced by the Innerbelt were steered. The Wildwood house was confined, nothing like they had in their old neighborhood. And Gibson, a child of 11 or 12 years old, watched the few white neighbors in his new neighborhood quickly move away.

The eminent domain process sowed discord, leaving some residents feeling duped, others thinking they’d made out and homeowners upset over neighbors getting better deals.

“You know, they came in and they’d have already determined the dollar range that they want to pay for each person's property,” Gibson said. “And so, if this person knows a little something, we'll negotiate a different price for them. But if this person doesn't, we’re going to give them less. You see what I’m saying?”

Sterling Lundy remembers the manicured lawn and flowers surrounding his grandmother’s big house on Bishop Street near the old Miracle Mart and the original Iacomini’s restaurant on Exchange Street, which closed in 1985. There are no houses left on that section of Bishop. The Innerbelt shortened the street, leaving a dead end like an amputated limb. Other side streets cleaved by urban renewal saw home values plummet in value relative to the rest of the city.

“That neighborhood was pretty filled up,” Lundy said of the streets around his grandmother Betty Reiter's home. “I know my grandmother's house was paid for or just about paid for, because that's why my aunt (who inherited the home) was upset. She didn't get what she thought she should have got out the house, because the house was kept up and everything. And I remember her. She was spazzing about that.”

The city offered disparately different amounts for homes of roughly equally value, sometimes less than $5,000 and sometimes closer to $10,000, but almost always about half what the homes were actually worth, Gibson said.

“The money they spent to build the Innerbelt, they could have spent that money in the neighborhood to revitalize the housing … [and] revitalize those neighborhoods and help those people with with their properties instead of just coming in and destroying them, and giving them peanuts for it,” said Gibson, who works for the United Way as a financial empowerment coach for low-income residents.

‘Gone’

Gibson described his carefree childhood on Livingston Street with the boundless freedom and adventure of the Little Rascals movies. No limits. Bucolic properties in an urban setting. Sustainable living.

To the survivors, the Innerbelt is a graveyard. If it had headstones, one would say “Here lies 854 Bell Street,” a twinplex owned by Lillie Jackson’s uncle.

“We had a big old backyard. We grew grapes. We made wine. We canned. We thought we were in the city,” joked Jackson, whose mother came from Alabama and father from Louisiana.

The family was forced out three times, starting with Bell Street property.

“That was the first house,” Jackson said. “Then we moved to 108 W. Bartges. And then after we left Bartges, we moved to 369 W. Chestnut St. And all of that [displacement] is through urban renewal. Gone.”

Jackson, a criminal justice chair for the Akron NAACP who founded the Akron-Canton Association of Black Social Workers, heard her dad talk about urban renewal at the Chestnut Street home. The family had intended to retire and stay there.

“But that didn't work out,” she said. “It was a beautiful house. It was four bedrooms and a basement, a full attic. We had a big backyard. My dad hunted. He raised hunting dogs. … My mother could make a rabbit stew that would make you want to slap yo’ momma.”

They were a civic-minded, working-class family, her dad in the union at Firestone, everyone voting “rain, sleet or snow.” Her parents ended up paying $10,000 for a house on Fernwood Avenue and she, an unmarried woman 18 years of age, stayed at the YMCA building downtown.

“When they got to Fernwood in ’72, that's where they were going to retire,” Jackson said of her parents. “And they did. My dad finally retired. But you know, he was so depressed. I didn't know anything at the time. I'm a social worker now. But I think back, he got laid off, and Firestone shut down.”

“My dad was so depressed," Jackson recalled of the year after urban renewal bumped her family for a third and final time. "He sat on his reclining chair. He didn't shave. He just sat there, watching news. He wasn't very verbal. He was depressed. He was really depressed.”

Reach reporter Doug Livingston at dlivingston@thebeaconjournal.com or leave a message at 330-719-1756.

This article originally appeared on Akron Beacon Journal: Akron residents recall life before Innerbelt buried their neighborhood