'We're not waiting': Maui community shows distrust in government following deadly wildfires

Maui faces a rebuilding challenge of historic proportions after the deadly wildfires that killed over 100 people and destroyed a beloved town. And some residents say their toughest opponent may be the Hawaii state government itself.

Much of the aid efforts happening in the charred community of Lahaina and elsewhere are community-run because people don't feel as if the government is stepping up fast enough.

“We’re not waiting for our mayor to say we can or can’t. We're like, 'People need help and we’re helping them,'” said Lianne Driessen, who was born and raised on Maui and is director of sales and marketing at Trilogy Excursions, a family-run catamaran tour company based in Lahaina.

Her family lost their home in the devastating fire. Trilogy captains and boats didn't hesitate to start rescuing people from the ocean or transport people along the coast during recovery efforts.

Many have been frustrated when it comes to the lack of response and continued transparency from state and federal officials in the days following the deadliest U.S. wildfire in over a century.

The concern comes after decades of low public trust in the government given Hawaii’s history of colonialism and slow-moving bureaucracy.

“There’s a general distrust in the government,” said Noelani Ahia, a Maui-based indigenous health care professional running for Maui County Council for Wailuku-Waihee this November. She is one of the Native Hawaiian activists on the ground providing mental health support for people with post-traumatic stress disorder from the fires.

“The government they put in was white supremacy-centered from the assimilation and possession of our land,” Ahia said. “The government we have now are offshoots of that.”

Hawaii lost its last reigning monarch in 1893 to a government of nonnative American businessmen, plantation owners and politicians.

As a remote island chain that must be self-sufficient, the wildfire aftermath is a pivotal opportunity for officials to prove themselves as the community continues to show its resilience, critics say.

More: 'Help is pouring in': How to assist victims in the Maui wildfires in Hawaii

Driessen added, “If we left it to our local government entity I think the rebuild is going to be incredibly slow.” She pointed out how the state took over five years to build a small pier out of Lahaina Harbor but with military assistance and dollars, the community could move much faster. “People need to know that.”

Officials continue to say that they were unprepared for the “unprecedented” wildfires, which doesn’t sit well with much of the public, especially when a fire weather watch was issued two days beforehand warning of tinder-like conditions.

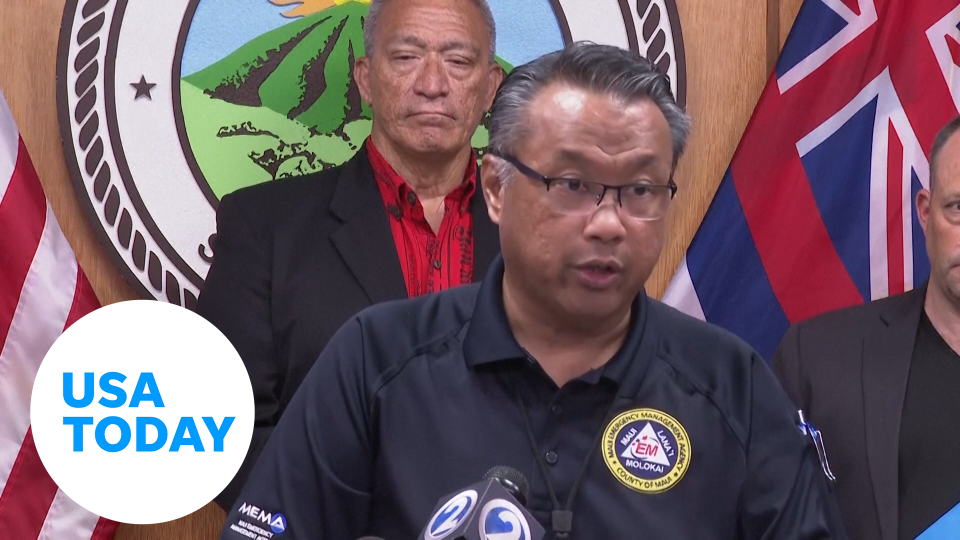

Maui’s fire chief and Herman Andaya, Maui’s top emergency management official, were not even on the island during the time of the fires, according to Honolulu Civil Beat. In the aftermath, it’s come to light that Andaya has no formal education or direct previous experience in emergency management.

During a Wednesday briefing, Andaya defended the decision, saying that the sirens would have sent people into the mountains, where the flames were. Instead, people were sent texts and voicemail warnings – however, cell service and power were already lost for most. Many ended up self-evacuating without knowing where to go.

Hours after making the comment, Andaya resigned.

As the fires spread rapidly across Hawaii's second-largest island, firefighters were stretched thin and resources were at capacity. The Maui Fire Department has not publicly answered Honolulu Civil Beat’s questions about response time and manpower.

“My guess is this is something that wildfires that the state is prepared for in the way it's prepared for hurricanes and tsunamis,” said Colin Moore, a political scientist at the University of Hawaii at Manoa on Oahu. “That’s not to excuse anything.”

Moore said that like in many other states, “trust in government in Hawaii is not particularly high,” although there is a uniquely “core distrust” in Hawaii, considering the island chain’s history of colonization.

He points out other incidents that have led to the public’s lack of faith in the government, such as in 2018 when a mistaken alert led residents to believe they were going to be hit by a North Korean missile, or the “mismanaged” rail project on Oahu that was almost a decade late in opening and took extra billions to build.

Hawaii is also known to have notoriously apathetic voters with some of the lowest voter turnout in the country since the early 2000s.

“A lot of amazing people work in the county and I can only imagine they feel horrible… but it points to a bigger picture of a government that’s tied to business,” Ahia said.

Just days after the tragic fire, developers have been reportedly asking survivors of the fire to buy their properties, where their homes have been burned to the ground. The island was already facing a housing crisis that’s been pricing locals out – now it’s even more critical.

Su-Mi Lee, the chair of the political science department at the University of Hawaii at Hilo, said that while tourism is the state’s major source of the state’s revenue, it seems – at least publicly – that residents are a main priority.

“It might be too soon to build sentiments for any politicians or hold anyone accountable as everybody is busy with helping with rescue efforts,” she said.

Evans Smith, a professor of political science professor at the University of Hawaii at Hilo and who has been living on the island for 20 years, told USA TODAY that he finds local and state governments in Hawaii are far less adversarial compared to their counterparts in other states.

Gov. Josh Green, who is also a medical doctor, built a relatively positive political reputation based on how COVID-19 was handled by the state when he was lieutenant governor. Recovery efforts for Hurricane Iniki in 1992, the last major hurricane to hit Hawaii, were well-approved, but that was a long time ago, Moore said.

A harmonious approach among state politicians is going to be tested in the coming weeks, months, even years, as the state recovers from the horrific tragedy, Smith said. He said many political leaders will have to show resilience and not be afraid to repeatedly ask for assistance at the highest levels for their constituents.

“There’s not a lot of political friction among elected officials and we’ll see if that holds up. I believe our leaders are going to face major challenges because this disaster is something that with even the best-laid plans, many weren’t prepared for,” Smith said. “There will be a hard learning curve going forward.”

Contributing: Terry Collins, USA TODAY

Kathleen Wong is a travel reporter for USA TODAY based in Hawaii. You can reach her at kwong@usatoday.com

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Maui residents have low public trust in government following wildfire