They were released from prison because of COVID-19. Their freedom didn't last long.

NEW YORK – Eric Alvarez felt something was off as he waited in a taxi outside a nearby Bronx halfway house. His fiancée, Eva Cardoza, was taking hours to come out on that June 2021 day from a home confinement check-in. She had tested positive for marijuana.

He went home alone. She was taken into custody and was eventually sent back to Danbury prison, the federal low-security camp in Connecticut where she had served nine years of a 15-year prison sentence for drug offenses before being granted home confinement to help cap the spread of coronavirus in May 2020.

More than a year later, Cardoza remains at Danbury, her lawyers said. Marijuana consumption for adults 21 and older is legal in New York.

Cardoza and two other women are at the center of federal lawsuits saying that people released from prison because of COVID-19 are now being sent back over minor infractions, such as not picking up a call from staffers overseeing their home confinement.

The lawsuits come as the Bureau of Prisons is facing scrutiny for reincarcerating people in home confinement over minor offenses, even as the agency has increasingly relied on the program to help reduce recidivism and prison populations.

"We're trying to change the conversation around mass incarceration and trying to limit our overuse of prisons, so why are you sending people back to prison for a minor infraction when they have families that they're taking care of?" said Marisol Orihuela, a lawyer for the three women and a law professor at Yale Law School in Connecticut. "When they have a job and they're furthering their education?"

The women in the lawsuits said they were not given due process before being returned back to prison. Lawyers in the three federal lawsuits said the court should have a transparent, constitutional process for the return of people who have home confinement infractions.

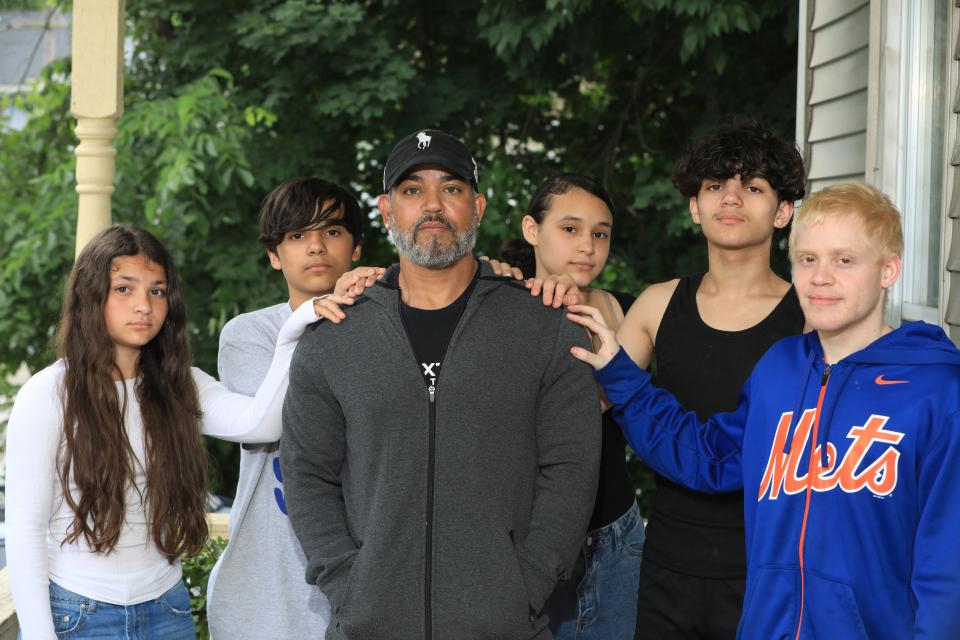

Cardoza's absence has left a gap: an ailing partner with debilitating disabilities, a home filled with several stepchildren and a 15-year-old daughter reeling from a sexual assault.

"What they did to us, it turned our life upside down," Alvarez said.

Before she was taken back to prison, reentry officials initially told Cardoza they had recommended that around 40 days taken off of her sentence for good behavior be added back to her home confinement sentence. Cardoza's lawyers contend the officials didn't recommend reimprisonment.

The second woman was also sent back to prison for a marijuana violation, while the third woman was reimprisoned for several minor infractions, including visiting an AT&T store without permission from the reentry staffers. She said she needed to fix her phone to keep in contact with officials and that she had gotten verbal approval for the stop.

The other women were eventually released after time in prison, while Cardoza remains incarcerated.

Thousands of prisoners sent home during COVID-19

During the pandemic, Cardoza was one of more than 43,000 people nationwide who were released from prison to home confinement during the COVID-19 pandemic. The BOP website said around 50,000 people incarcerated at its facilities had recovered from coronavirus and around 300 had died.

The massive CARES ACT granted then-Attorney General Bill Barr the option to broaden the use of the home confinement program, which had previously only been allowed to be used at the very end of a person's sentence.

Barr opted to allow thousands of people to receive home confinement much earlier, shaving off years from a person's sentence in some cases.

At the conclusion of the national pandemic emergency period, the formerly incarcerated group would've been imprisoned, according to a legal opinion that came out during the Trump administration.

In December, the Biden administration's Justice Department reversed the decision, allowing those people to stay home.

Last year, more than 3,000 people were released to CARES ACT home confinement, according to a records request put in by the Prison Policy Initiative, a nonpartisan public think tank.

Those who were released to home confinement were told they must follow specific rules. They have to keep reentry professionals – specialists who are often working for companies contracted by the BOP – updated on their whereabouts. They often wear electronic monitoring and receive special permission to visit stores or other locations. They can go to work or school.

But if someone on home confinement was found to have an infraction, such as missing a check-in or a failed drug test, they could be returned to prison.

The Bureau of Prisons told USA TODAY that 407 people had their home confinement revoked. Of those, 212 were returned because of misconduct in violation of program rules, such as alcohol use and drug use; 69 were returned after an escape, such as an unauthorized absence from custody; and 11 were for new criminal conduct and other violations.

The Bureau of Prison's Inmate Discipline Program requires several steps before returning a person in home confinement to prison, including a disciplinary hearing, written notice of the allegations and the ability to present evidence.

The BOP told USA TODAY its Administrative Remedy Program allows people to have "any issue related to their incarceration formally reviewed by high-level" officials.

But lawyers involved in the lawsuits said their clients did not have hearings, written notice or the ability to present evidence. They said their pleas for review were ignored and noted that the cumbersome, monthslong process can lead to collateral damage, such as a child going back into foster care while the parent is in prison.

James Felman, former chair of the criminal justice section of the American Bar Association, said the reality is that a person in BOP custody is not given the same rights as somebody who is arrested and accused of a crime.

“We typically think you have to have some kind of a hearing and you have to have due process. That's not the case here,” said Felman, a criminal defense lawyer in Tampa, Florida. He has no direct involvement with the three federal lawsuits.

Felman said he has heard of other cases in which a person on home confinement because of COVID-19 has been remanded back to prison for similarly minor infractions as described in the lawsuits.

“One day they’re out on home confinement, and then the next step is they just come and pick them up and take them away and they're given very little explanation, even at the time, as to what they've done wrong,” Felman said.

Erica Zunkel, associate director of the Federal Criminal Justice Clinic at the University of Chicago Law School, said the accusations raised in the lawsuits do not seem to meet BOP procedures on how to deal with violations of home confinement. She noted other similar cases, such as the reimprisonment of Gwen Levi, a woman in her 70s who was reincarcerated after missing phone calls while she was at a computer class. After her case stirred a significant outcry, a federal judge decided to grant her compassionate release in July 2021.

“It just doesn't seem to comport with justice and fairness and there seems to be a large degree of arbitrariness to how these things are happening and people and families are really, really paying the price for that,” she said.

Kevin Ring, president of criminal justice advocacy organization FAMM, said anyone on home confinement should be careful to follow the required rules. But he said consequences should match the violation and people shouldn't face years of imprisonment for missing a call. He also wants to see more explicit rules on how infractions are handled.

"People are not meant to be on monitors for years and years," he said. "You're going to screw up, even if you don't want to."

Marc Levin, chief policy counsel at the Council on Criminal Justice, a nonpartisan think tank, said it’s “mindboggling” that the federal system is still resorting to this sort of punishment. He noted many states, such as Texas, Alabama and Arkansas, have more lenient systems for state prisoners on parole, including a parole system where the punishment for violating any requirements might be an increase in supervised home confinement, not a return to prison.

And before the person is reimprisoned, he said, there is typically a hearing before a judge.

Returned to prison for minor infractions

The federal lawsuits focus on three women. One of them, Nordia Tompkins was released on home confinement in June 2020 after nearly four years at Danbury prison for conspiracy to distribute a controlled substance. After being released, Tompkins, of Sullivan County, New York, spent a year on home confinement reconnecting with her daughters, furthering her education and preparing for a future career in cosmetology, according to her lawsuit and prison officials.

A string of violations sent her back to prison and her then-12-year-old daughter back to foster care.

In May 2021, Tompkins received a violation after reentry staff could not reach her by telephone while she was on an approved pass to be at school.

The following month, an electronic monitor showed her to be at an unauthorized address for about an hour and 15 minutes. That same month, an unauthorized stop to get her phone repaired at an AT&T store sent her back to prison, according to court documents.

Tompkins said reentry staff had authorized her to get her phone repaired – something she needed to have to keep in contact with officials.

"Upon my release, I did everything I set out to do," Tompkins said in a letter dated June 28, 2021. "I got my daughter out of foster care back into my care, I got a job and I reenrolled in school."

She added, "Up until now I have worked so hard to settle back into society the right way."

At a hearing, Tompkins was given a proposed punishment of a loss of around 15 days of good time credit. The document did not mention, her lawyers said, revocation of her home confinement but that’s just what happened.

U.S. Marshals took Tomkins into custody and she was later reimprisoned. Her lawyers said Tompkins received no written notice of the BOP’s decision to revoke her home confinement and imprisonment.

BOP officials motioned to dismiss her case, saying, "She proved herself incapable of complying with the conditions of community custody through her repeated misconduct."

After the lawsuit was filed, Tompkins was sent to a halfway house, where she receives passes for work, but can't gain custody of her younger daughter.

The third lawsuit involves Virginia Lallave, a mother of two who had gotten a job and was taking care of her father on dialysis treatment after being sentenced to nearly four years in prison, followed by three years of supervised release. She was reincarcerated for a positive marijuana test in February, more than a year after she was released to home confinement in June 2020.

Lallave’s lawyers asked that she be returned to home confinement while awaiting disciplinary hearings and a toxicology report. The BOP did not respond before taking her back to prison, her lawsuit stated.

Lallave did receive written notice that she could lose around 40 days of good time credits for the violation. She was not given notice that prison time was a consideration.

A federal judge ordered the release of Lallave pending adjudication of her case. Still, her lawyers said Lallave continues to be supervised by the private prison contractor and regularly is woken up in the middle of the night with required check-in phone calls or texts.

This month, a judge dropped the case after the BOP released her and decided that it would not incarcerate her further for the marijuana test, her lawyers said. But, the judge declined to weigh in on the due process concerns in the case.

The BOP said it could not comment on the three cases.

"For privacy, safety and security reasons, the BOP does not discuss whether a particular inmate is the subject of allegations, investigations or sanctions in prison, nor do we comment on the conditions of confinement for any individual or group of inmates," it said in a statement.

Sarah French Russell, a lawyer in the three lawsuits and a law professor at Quinnipiac University School of Law in Connecticut, said the three women have appealed through the administrative system and the "BOP has not even answered them."

"The BOP's citation to the administrative remedy system is yet another attempt to avoid accountability for its conduct in ripping our clients away from their families and jobs without a fair hearing," said Russell, also director of the school's legal clinic.

The BOP said in court documents that if an incarcerated person doesn't receive a response within the allotted time period, that person may "consider the absence of a response to be a denial at that level."

A daughter missing her mother

In the meantime, Cardoza's seizures and other medical conditions have worsened since she has been back behind bars.

At home, her presence is acutely missed, according to Alvarez, her fiancé. In the year that she had been home, Cardoza had established herself as the maternal figure in a house that included children ranging from 11 to 15, along with Alvarez's 26-year-old son, who has special needs.

The family said Cardoza was the one to cook meals, clean and help the children with homework. Meanwhile, she cared for Alvarez, who has an enlarged heart and other medical conditions that have placed him on disability for the past two decades, court documents said. His ailments often make it difficult for him to get out of bed.

Cardoza's absence is perhaps most felt by her 15-year-old daughter. She was 3 when her mother was incarcerated and went to live with her grandmother. After her mother's release from prison, they had reestablished a strong bond.

"It really stresses me out because I cry at night. And it's just, like, I always want to walk into my stepdad's room, hoping that my mom’s there. But she's never there," the daughter said.

During her mother's recent stint in prison, the girl said she was sexually assaulted by her godfather. USA TODAY does not typically name children who are the victims of sexual violence.

As hard as he tries, Alvarez said it is difficult for him to comfort the daughter in her moments of desperation. Once a good student, she struggles to keep focus in class. At nighttime, she has night terrors. She fears older men.

Although she is in therapy, the teen said she knows what she really needs: her mother.

"She would give me that comfort and that mother hug that every child would want in their whole entire life," she said.

She does get the opportunity to talk with her mother. In those moments, she said her mother seeks to soothe her, saying, "I'm going to be home pretty soon."

Tiffany Cusaac-Smith covers race and history for USA TODAY. Follow her on Twitter @T_Cusaac.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: They were released from prison because of COVID-19 but got sent back.