They Were Switched at Birth—and Didn’t Find Out for 50 Years

Like any new mother, Kathryn Jones thought the baby she was handed at Duncan Physicians and Surgeons Hospital on May 18, 1964, was the most beautiful child she had ever seen. “I loved her from that second that they laid her in my arms,” she said in a recent interview, pausing before adding: “Never once did I think she was not mine.”

But according to a lawsuit filed in Stephens County District Court in Oklahoma, the infant Jones cradled and took home was not her biological daughter at all. Citing multiple home DNA tests, Jones alleges that employees at the hospital handed her the wrong baby more than 50 years ago, leading her to raise a child who was not her own.

Now, she and her daughter are struggling to pick up the pieces.

“It was like somebody had ripped out a part of my heart,” Jones said of the day in 2019 she learned of the alleged mix-up. “I just couldn't deal with it.”

Tina Ennis, the child Jones raised and loved as her own, describes her childhood—somewhat ironically now—as “normal.” The people she knew to be her mother and father split when she was just 2 years old, and Jones remarried a few years later, to the man Ennis still calls “Dad.” He was a house painter, her mother a telephone operator. She has an older sister, Brenda, with whom she is still extremely close, and a little brother eight years younger. She was always a little taller and thinner than the rest of the family, but her mother said she just looked like her biological dad. “I never felt like I didn’t belong,” Ennis said.

Then, in the summer of 2019, Ennis and her now 26-year-old daughter took an at-home DNA test from Ancestry.com. Jones’ father, like her own, had left when she was very young, and Ennis wanted to track down her grandfather. But when the results came back, they were filled with names she didn’t know. She called her mother to ask her if she knew anyone named Brister, because they dominated her family tree. She did not.

Eventually, Ennis convinced Jones to take a DNA test, too. When the results came back—to an email address that Ennis runs on Jones’ behalf—they were even more puzzling. Neither Ennis nor her daughter showed up on Jones’ family tree. Ennis thought maybe it was because she had stopped paying the Ancestry.com monthly fee, but when her daughter called the support line, the woman who answered told her that wasn’t how it worked. “You know, you find out some interesting things on Ancestry,” the woman told her.

Ennis’ daughter became convinced that she had somehow been switched at birth, but Ennis wasn’t sure. Through a little online sleuthing, her daughter tracked down a local woman who was born on the same day as Ennis, and who looked strikingly like Jones. She convinced Ennis to send the woman a Facebook message, even though, as Ennis put it, “if I were to get [that message], I would think that person was crazy.”

The woman on the other end of the message, Jill Lopez, didn’t think Ennis was crazy—though her husband did suspect she could be some kind of scammer. Lopez was raised in a rural part of Oklahoma by Joyce and John Brister, a stay-at-home mother and a dad who worked in the oil business. She had older sisters and a few close friends nearby, and her grandmother lived less than a mile away. But Lopez resented her country life, always feeling too far away from where everything was happening. She eventually moved to the small city of Lawton, which was where she was living when she received Ennis’ message.

Tina Ennis, Kathryn Jones and Jill Lopez.

Lopez agreed to take a DNA test, too, and the results came back faster than either of them expected. She called Ennis the day they arrived to give her the news, but she didn't have to. Ennis had already seen the alert come in on her mother’s email account, telling her that she had a new family connection—Lopez. It was then that Ennis realized she’d been hoping that none of this was true. "My heart just sank [in that moment,]” she recalled, “because I was just like, ‘This is for real.’”

Ennis didn’t want to tell Jones what she’d discovered until she was absolutely certain, but after meeting with Lopez at a local restaurant and talking for several hours, she knew there was no denying it. She arranged a meeting with her mom and two siblings to break the news.

At first, Jones admits, she resisted the information, telling Ennis over and over that she had to be her daughter. But when they showed her a picture of Lopez, she said, the first thing she thought was, “Where was I when that was taken?” and “I don’t remember those clothes.”

“Because she actually looked just like me,” Jones added. “And it devastated me.”

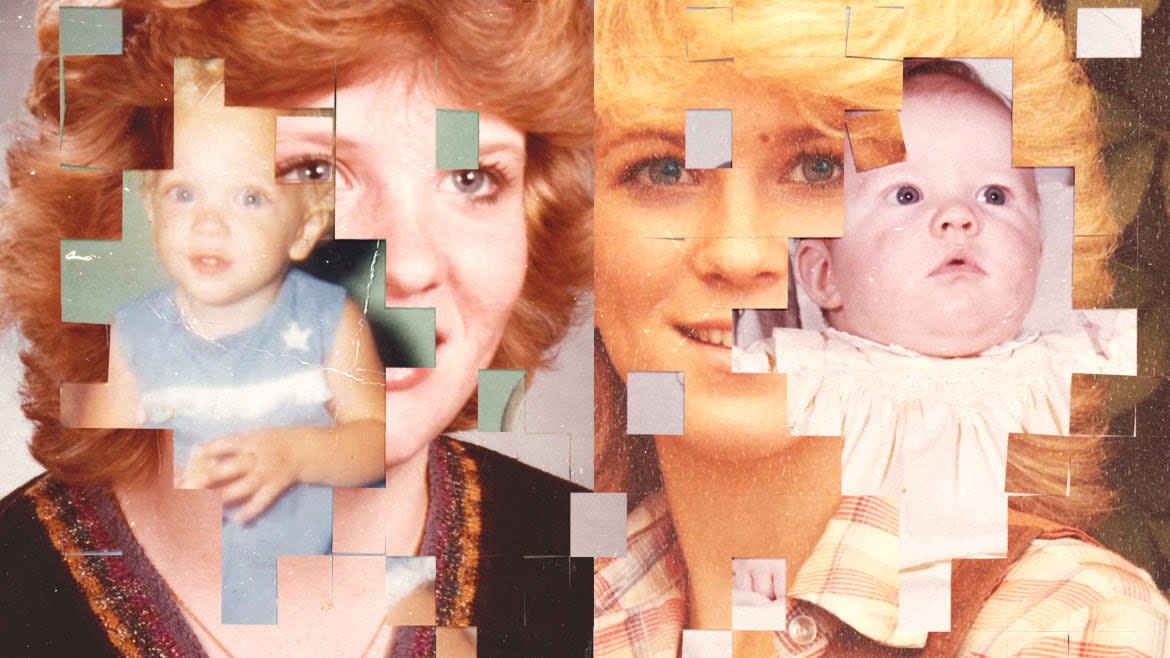

Tina Ennis and Jill Lopez as infants.

It’s difficult to say how many babies are switched at birth in the U.S. The National Institutes of Health does not keep track, and hospitals, understandably, don’t publicize the information. A Baltimore Sun article from 1998 claims 28,000 newborns are mixed up every year, but the study it cites is not linked and the article itself is promoting a newfangled line of baby-tracking devices.

The general consensus is that most mix-ups are discovered before families leave the hospital. Hospitals have a range of protective measures in place, such as putting an identification band on the baby as soon as it is born, to ensure any mistake is quickly rectified. How a switch with Ennis and Lopez could have happened is unclear; the suit is light on the details, and the doctors who delivered both babies are long since deceased.

But the results, all three women agree, have been Earth-shattering. Jones is wracked with guilt for all the birthdays, Christmases, graduations, and weddings she missed for her biological daughter, but is also terrified of losing Ennis. Realizing that Ennis’ children were not her biological grandchildren, she said, “was one of the low points of the whole thing.”

“I felt like I was losing my daughter and my grandchildren too,” she said.

Ennis, meanwhile, has had to deal with another pain all her own. Her apparent biological parents—the Bristers—died many years ago, before she had a chance to meet them. Lopez’s family has sent her pictures and told her stories, but it’s not the same. Sometimes, when she gets to thinking about it, it’s hard not to feel a little jealous. “Jill got to be with my real parents, and now she gets to be with my parents I grew up with,” she said. “I didn’t know what to think about it at first, but the more I think about it, it makes me really sad.”

Joyce and John Brister

That’s the thing about this whole story: There is no big, Disney-esque, one-happy-family moment at the end. Nearly three years later, all three women are still struggling with how to feel, and how to have each other in their lives. Both women are married and have families of their own: Ennis has three children; Lopez two. Ennis is a career postal service carrier, Lopez recently switched from teaching to selling real estate.

Ennis says she has only seen her biological siblings once or twice; she can’t tell if she’s keeping them at an arm’s length or vice versa. She and Lopez get along fine, but they don’t see each other often—they’re both too busy, and it’s all a little too hard. Sometimes, when Jones spends time with Lopez, she doesn’t tell Ennis and her sister. She doesn’t want them to get jealous.

The three women are suing Duncan Regional Hospital—the hospital their lawyers claim took over liability for Duncan Physicians and Surgeons Hospital after it merged with other local hospitals in 1975—alleging recklessness and negligent infliction of emotional distress. The hospital has denied these allegations, claiming it is not the same entity where the two were allegedly switched. (A judge denied the hospital’s motion to dismiss on these grounds last month.). Reached by phone, a lawyer for the hospital declined to comment further.

In the meantime, the women are still figuring out what their new family will look like. Ennis and Lopez each brought their children to Jones’ house for Christmas this year; they say the grandkids got along swimmingly. It’s their mothers who took a while to feel comfortable with it all.

“I just had to get my emotions straight for a while, because it’s a whole lot to get your mind around,” Lopez explained. “Like, you had a mom and I had a mom, and now I have a different mom.”

“From the outside we all probably look pretty good,” Ennis added. “But in my opinion, it has not been something I would wish on anyone.”

Get the Daily Beast's biggest scoops and scandals delivered right to your inbox. Sign up now.

Stay informed and gain unlimited access to the Daily Beast's unmatched reporting. Subscribe now.