Hitchcock’s Adaptation of One of Roald Dahl’s Most Famous Stories Edited Out the Racism. Wes Anderson Kept It In.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

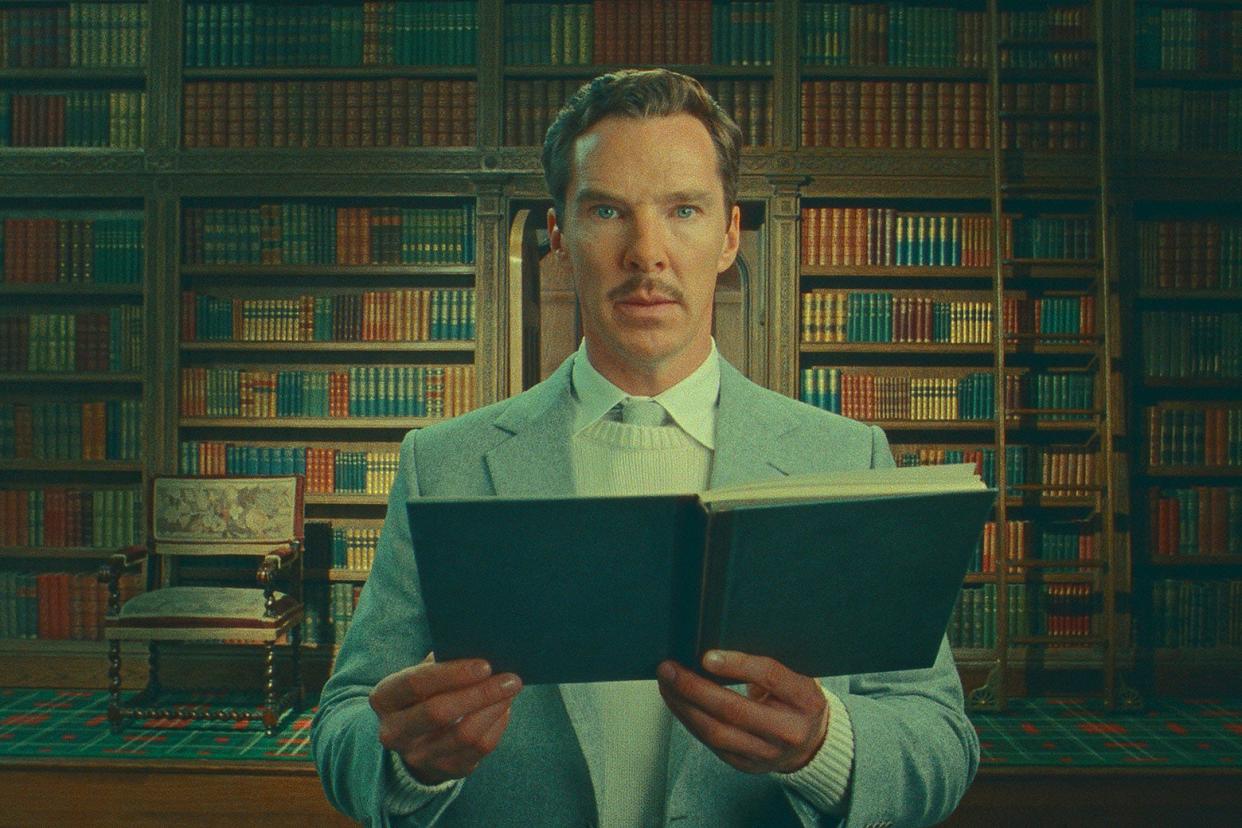

The four short films Wes Anderson has just released on Netflix—The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar, The Swan, The Rat Catcher, and Poison—are clearly intended as companion pieces. Adapted, like Anderson’s Fantastic Mr. Fox, from the stories of Roald Dahl, the shorts use a rotating repertory company of actors including Benedict Cumberbatch, Ben Kingsley, Dev Patel, Richard Ayoade, Rupert Friend, and Ralph Fiennes, the last of whom also plays Dahl, narrating the stories from a meticulous re-creation of the real Dahl’s writing hut. Their credits roll in the same yellow hand-scrawled typeface, and they share a flamboyant theatricality that makes them of a piece with Anderson’s most recent feature, Asteroid City. But Netflix has been strangely reluctant to present them as a set. Henry Sugar got a gala rollout at the Venice Film Festival last month, but critics weren’t even allowed to see the other three shorts in advance, and they’re not obviously linked on the streaming service’s website. But now that they’re all out, you can see why they were eager to keep Henry Sugar set apart. Henry Sugar, which, at 41 minutes, runs more than twice as long as all the others, is a delight, a playful and upbeat story about a wealthy man (Cumberbatch) who develops a complicated idea for making himself even wealthier, and in the process realizes he’d rather give his money to charity. The subsequent shorts come to progressively darker ends, ranging from the melancholy to the macabre. Their visual presentation and rapid-fire dialogue make them instantly recognizable as Anderson’s, but their tone takes him into territory so unexpected it might be disorienting if his hand were not so sure.

Anderson has said it was the story’s nesting-doll structure that drew him to Henry Sugar in the first place—he later used a similar series of matryoshka-like frames for The Grand Budapest Hotel—and he realizes its concentric narratives with dazzling fluidity. We begin with Dahl (Fiennes) at his writing board, sharpening his pencils to commence the tale of Henry, as the camera slides sideways between sets to physically enter the story. In a notebook shelved among the books in his family’s prodigious collection, Henry encounters the handwritten account of one Z.Z. Chatterjee (Patel), a doctor in a Calcutta hospital, who relates in turn the story of Imdad Khan (Kingsley), a carnival performer and mystic who has developed the ability to see without opening his eyes. There are even more layers than that: Dahl eventually reveals that Henry’s story was brought to him by an intermediary, meaning that when Khan is telling his own story, about the yogi (Ayoade) who taught him the meditation techniques that allow his sightless vision, we are as much as five levels deep. (That’s as many as Inception.) It’s not especially important to know whose story you’re in at any given moment, since all the characters effectively speak with Dahl’s voice, reciting his prose right down to the “I said.” At one point, Chatterjee describes the look of astonishment on a colleague’s face, and the colleague swivels around to make sure the camera gets a good look at it.

Barring the occasional Dahl drop-in, the other shorts dispense with the frames within frames. But they hold on to Henry Sugar’s ornate constructedness, as meticulous and mysterious as a Joseph Cornell box. In The Swan, the story of a young boy in the British countryside beset by sadistic bullies, Rupert Friend’s narrator strolls along hedgerows and wheat fields that mask hidden doors through which stagehands and supporting characters come and go. It’s a brutal tale of childhood barbarism whose protagonist (Asa Jennings) is, among other things, tied to a set of active train tracks and shot with a hunting rifle, but Anderson keeps the violence implicit and offscreen, as if the storyteller himself can’t quite bear to remember the details. That’s less true for The Rat Catcher, the most purely grotesque of the shorts, which features a snaggletoothed Fiennes spitting out a crimson gusher of rat’s blood.

Poison is the most unnerving of the lot, even though the threat that animates it may be entirely imagined. Harry (Cumberbatch), an Englishman living in postcolonial India, tells his partner, Woods (Patel), that there’s a krait—a small, intensely poisonous snake—curled up on his belly, having slithered under the sheets while he was reading in bed. Unable to move or speak above a whisper, he hisses instructions to Woods under his breath, eventually securing the arrival of a local doctor, Ganderbai (Kingsley). But the doctor can only do so much to treat a snakebite that hasn’t happened yet, and the tension between the two grows until Harry spits out a racist tirade, calling Ganderbai a “Bengali sewer rat.”

Poison is the most frequently adapted of these stories, having been filmed for Alfred Hitchcock Presents, by the man himself, in 1958, and for the Dahl anthology series Tales of the Unexpected in 1980. Hitchcock’s version ditched the story’s racial subtext entirely, and both TV versions make Harry an alcoholic who has just gone on the wagon, muddying the question of what the poison in Poison is meant to be. The later version, whose introduction by a real live Dahl makes for an interesting comparison with Fiennes’ incarnation, does make its protagonist’s antipathy to his current surroundings clear, introducing him reading aloud from an anti-Raj anthem. But it’s their drunkenness that gets both men in the end, setting up a pair of moralizing twists that are at odds with Dahl’s unsettling and unresolved ending.

Anderson strips Poison, which runs only a few pages in print, back to its essence. Like the other post–Henry Sugar shorts, it runs barely over a quarter of an hour, which allows for a degree of intensity that might be exhausting at feature length. As the corner of Cumberbatch’s frozen mouth twitches, knowing any movement might cause the krait to strike, you tense up alongside him, even as it becomes more clear that the sharp tone of his exchanges with his Indian friend aren’t just a product of momentary stress. There’s a cruelty to these stories that makes you grateful for the chance to take a breath when they’re over. These are some of Anderson’s most beautiful films, and some of his ugliest subjects.

Race has rarely been an issue in Anderson’s movies. His ensemble casts have become less overwhelmingly white, but his universes tend to operate according to their own laws rather than the real world’s. (Even in his most overtly political movie, The Grand Budapest Hotel, the rise of European fascism is evoked only through stylized allusion.) And Poison seems like it’s going to leave the cause of Harry’s antipathy for his local doctor just under the surface until it bursts free in a brief tirade. But the short doesn’t treat this explosion as a catharsis, or a purgation. Kingsley’s doctor recounts the story of a sheep bitten by a krait, and how, when it was cut open after death, “its blood ran pitch, black as tar.” It only takes a drop to poison a person, and then there’s no saving them.

Rather than a tidy resolution, Anderson’s Poison ends both its own story and the cycle of Dahl shorts on an unnervingly indefinite note. It works the way a good short story does, outlining a situation or state of being and then leaving us to imagine the rest. (Poison’s brief cutaway to Patel’s memory of a past hospital stay, a raw, freshly stitched gash stretched across his forehead, is the most jarring image in Anderson’s entire oeuvre, the more so because the short never returns to or explains it.) Few if any directors of Anderson’s stature have taken advantage of streaming to produce work outside the constraints of feature film running times, let alone major shortform work that’s not just an opportunity to experiment or rake in some spon-con cash. The triumph of Henry Sugar and its companions should be an inspiration for others to follow suit.