How West Coast universities, colleges grapple with 'literal overheating' of buildings amid recent heat wave

PALM SPRINGS, Calif. — Within the first few weeks of moving into her dorm building at the University of Nevada, Reno, Mei Wong found living in her room to be unbearable.

As temperatures soared to the high 90s and 100s during first couple of weeks of September, Wong and her roommate struggled to settle in their room. Since her dorm is an older building and has no air conditioning, Wong had to run four fans in her room throughout the week.

“We couldn't do anything without sweating,” Wong told USA TODAY.

Wong also tried to keep her windows open because her room would “start to get musty” without natural ventilation. Reno also faced poor air quality that week as smoke from the Mosquito Fire — California’s largest fire of 2022 — created unhealthy to hazardous conditions.

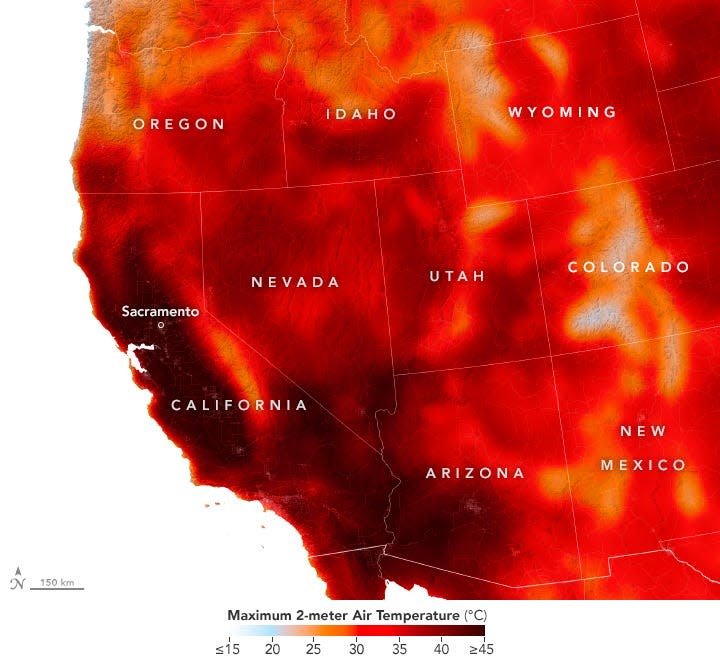

The historic heat wave that sweltered the West in early September, breaking records and straining California’s power grid, forced colleges and universities across the region to further assess extreme heat events.

College campuses, specifically students and faculty on the West Coast, struggled with the intense heat wave. They have warned their communities of the excessive heat but high temperatures highlighted issues of campus infrastructure.

While it isn’t uncommon to experience heat waves in these areas, the most recent heat wave prompted unprecedented conditions.

“These heat waves can be devastating to schools because poor environmental conditions can very easily not only be a distraction to students but have more severe health consequences,” said Paul Ullrich, professor of regional and global climate modeling at the University of California, Davis.

Climate and sustainable design and planning experts advocate for the investment in infrastructure adaptation, noting how current campus infrastructure has inadequate cooling systems or lacks cooling systems.

OCEANS RISE, HOUSES FALL: The California beach dream home is turning into a nightmare

'Literal overheating of the buildings'

Older buildings have air conditioning systems that aren’t designed to handle high levels of heat and are unable to operate for the long hours they currently run at, according to Paul Chinowsky, professor emeritus in civil engineering at the University of Colorado, Boulder.

Chinowsky said that in addition to internal systems breaking down in buildings, the urban heat island, such as streets, buildings, and lack of green space intensifies heat in the areas people live and work in.

Many older buildings are unable to cool down and are degrading at a faster rate against the high demand for energy.

“There's just a literal overheating of the buildings,” Chinowsky said. “The second thing the heat is really doing is degrading the building materials — seals around windows, roofing materials — it's literally causing things to melt because it's so hot.”

Amid the recent heat wave, campus communities grappled with buildings unequipped for severe temperatures.

Pomona College students struggled with the heat as 64% of residence halls don't have air conditioning, according to the Claremont Colleges’ student newspaper, The Student Life.

Occidental College also faced similar conditions. The school’s student newspaper, The Occidental, reported that 46% of dorms do not have air conditioning and Occidental’s administration offered students to sleep in common areas of non-residential buildings.

A majority of student residence halls at Occidental were built prior to 1966, when air conditioning was not a standard feature, according to Rob Flot, vice president for student affairs and dean of students at Occidental.

'IT COULD HAPPEN TOMORROW': Experts know disaster upon disaster looms for West Coast

Flot noted the lack of air conditioning in residence halls is “not unusual in Southern California, where almost every college and university campus has residence halls without air conditioning.”

“It's at night when students are trying to get some sleep, that heat becomes a major issue,” Flot told USA TODAY.

For students who lack air conditioning in their rooms, Occidental transformed secured common areas in air-conditioned residence halls into an optional sleeping space with roll-away cots, Flot said. The college also extended operational hours in other air-conditioned common areas, such as the library where employees came to work for the Labor Day holiday.

“The unprecedented conditions this fall have made all the more urgent our efforts to best prepare for rising temperatures,” Flot said in an email.

The college will continue to explore other cooling measures, such as expanding their inventory of evaporative coolers as a short-term solution, and are looking into longer term measures, according to Flot.

At the University of Reno, Nevada, circulation systems at residence halls are designed to keep temperatures "as low as possible," Kerri Garcia Hendricks, executive director of marketing and communications at the University of Reno, Nevada, told USA TODAY.

Garcia Hendricks said there are currently no plans to renovate residence halls that have no air conditioning. Instead, the university focuses on providing outreach on how to maintain cool conditions indoors, such as opening windows at night and closing windows and blinds during the day. Students are also encouraged to use and visit cooler locations on campus.

How campuses reduced energy usage during intense heat waves

The University of California, Riverside, has seen utility and electric bills increase due to electrical consumption needed to cool buildings, according to Gerry Bomotti, UC Riverside vice chancellor for budget, planning, and administration.

While Riverside is used to the hot climate, longer periods of heat “will have impacts on the life spans of our building equipment, so we will have to be prepared to replace items on a shorter time frame,” Bomotti said in an email.

Changes to the central plant, heating, ventilation, and air conditioning operations at the University of California, San Diego, were implemented during the heat wave and led to limited higher overall space temperatures in many campus buildings, according to university spokesperson Leslie Sepuka.

Infrastructure improvements to expand the chilling system capacity on the San Diego campus have been underway since February 2022, Sepuka told USA TODAY.

Currently, dorms at the university are not air-conditioned and “are designed with operable windows and exterior features oriented to take advantage of prevailing ocean breezes,” Sepuka added.

Sepuka noted that recurring heat waves place a high power demand on state and regional electric grids, prompting potential grid instability and power loss which can be seen during scheduled rolling blackouts or unscheduled failures.

But UC San Diego is "protected" from these power grid instabilities due to the campus' microgrid system, Sepuka said.

'WE CANNOT AFFORD TO DELAY': California becomes first US state to begin ranking extreme heat wave events

'Cooling is no longer a luxury'

Hot weather is "a natural part of life in the low deserts of Arizona," Alexander Kohnen, Arizona State University's vice president of facilities development and management, told USA TODAY.

While air conditioning is a standard in buildings and people who live in the region understand heat exposure awareness, the increasing frequency of extreme heat waves has impacted the university's campus in several ways.

Currently, the university is able to cool the campus through three district energy plants with over 32,000 tons of capacity, according to Kohnen. Solar arrays are also used to provide shade in parking areas, walkways, and a softball stadium.

But Kohnen said the university has experienced solar array inverter shutdowns due to inverter overheating, and campus landscaping, including shade trees, has been under stress due to extreme heat.

The university plans to reduce energy usage and has designed newer buildings to be energy efficient, such as implementing radiant ceilings and chilled beams. Kohnen said the university also plans to replace its distribution system and convert its heating system to hot water in the next decade.

Another cooling alternative the university uses are "innovative" heating, ventilation, and air conditioning technologies, such as indirect evaporative cooling and economizer cycles to provide thermal comfort, according to Kohnen.

STUDENTS STRUGGLE TO FOCUS: Hotter temperatures a threat to students in schools with no air conditioning

"We are continuing to look at ways we can improve our ability to use energy and water responsibly," Kohnen said in an email. "In addition to implementing adaptive and resiliency measures, ASU is also addressing the root cause of the problem by eliminating its carbon footprint."

Meanwhile, Portland State University has had a Climate Action Plan since 2010, according to university spokesperson Christina Williams.

The university "is beginning a comprehensive update to the plan which will include significant work on climate adaptation and will help direct future capital spending," Williams said in an email.

Williams noted that for the most part, buildings on Portland State University's campus have not been designed for extreme temperatures due to the region's temperate climate.

Similar to Portland State University, the University of Washington has traditionally benefited from the Pacific Northwest's temperate climate.

Many campus buildings at the University of Washington were designed to be reliant on passive and natural ventilation strategies, according to university spokesperson Victor Balta. Only in recent years has mechanical cooling been implemented in larger campus spaces.

Balta said climate change has modified the university's need for cooling and the university has new design conditions for the next few decades that account for prolonged heat events.

The university has seen mechanical cooling and high-voltage electricity systems reach or come close to capacity during excessive heat events, according to Balta. Currently, the campus has nearly 32,000 tons of cooling capacity.

"Cooling is no longer a luxury, but rather it is becoming a foundational requirement in providing the most productive building environment for students, faculty and staff," Balta told USA TODAY. "To adapt, we will need to modify our buildings to add cooling where it previously was not provided, and increase cooling capacity in spaces where the systems were designed to an older standard."

Alternative cooling and sustainable solutions? Think trees and fans.

While implementing more air conditioning in buildings is an option, this will only increase energy usage and create excessive levels of gas emissions.

An air conditioning system in a building can run at an estimated cost of $1 to $3 million per building, according to Chinowsky. That number can double for a 12-story dorm building.

“So if you're thinking about multiples of those, you very quickly can get up to, easily for a campus, a $100 million problem,” Chinowsky said.

Some alternative cooling methods are planting shade trees outside buildings and placing shade structures around buildings. People will have to start creatively thinking of alternate solutions, according to Chinowsky.

To reduce energy demand, Chinowsky said older building systems will have to be replaced with new systems that are more efficient and use less energy. People will also have to rethink the different hours people work, such as using buildings later in the evening and having a break in the middle of the day.

“We need to upgrade systems and we need to go back and actually relook at how we did buildings in the 1930s before we were doing air conditioning and using more airflow, using more natural cooling in the buildings, really just by airflow in the buildings,” Chinowsky said.

Another method is using more electric fans, which are an effective, sustainable, and cooling technology, according to Stefano Schiavon, professor of architecture and civil environmental engineering at the University of California, Berkeley.

Schiavon’s research focuses on reducing energy consumption in buildings and helping people be healthier and more comfortable within buildings.

Schiavon also proposed more usage of natural ventilation and the thermal mass of a building, which can provide proper shading and help maintain comfortable conditions indoors. Another solution is the use of electrical battery-operated systems that shifts the load from the power grid when it is strained or unusable.

While there are several alternative cooling methods and solutions, Chinowsky said people have to start looking at future projections in order to significantly change the way infrastructure is designed.

“What's really going to make a difference is when we start accepting that these heat waves are here,” Chinowsky said. “They're going to stay and we need to address that and not just as ‘Oh, this is an anomaly.’ It really is the new normal.”

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Experts urge sustainable infrastructure at colleges after heat wave