As Western unity on Ukraine falters, Putin eyes a slow-burn win

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

This is the moment Russian President Vladimir Putin has been waiting for: when he doesn’t really need to do much, and can call it a win.

The static frontlines in Ukraine are slowly hardening as the snow deepens. In Kyiv, there is a palpable sense of once-insurmountable morale ebbing slightly. There is open talk of disagreement between the commander-in-chief and the chief of staff – Volodymyr Zelensky and Valery Zaluzhny.

Russia is no longer losing the war, or the terrain it seized, and so Ukraine is definitely not winning it. Across European capitals, elections loom and even the farmers of stalwart ally Poland are picking quarrels with their Ukrainian neighbours.

In the United States, Senate Republicans blocked a legislative package including $60 billion in aid for Ukraine from advancing Wednesday evening, amid a standoff with the Democrats over US border and immigration policy.

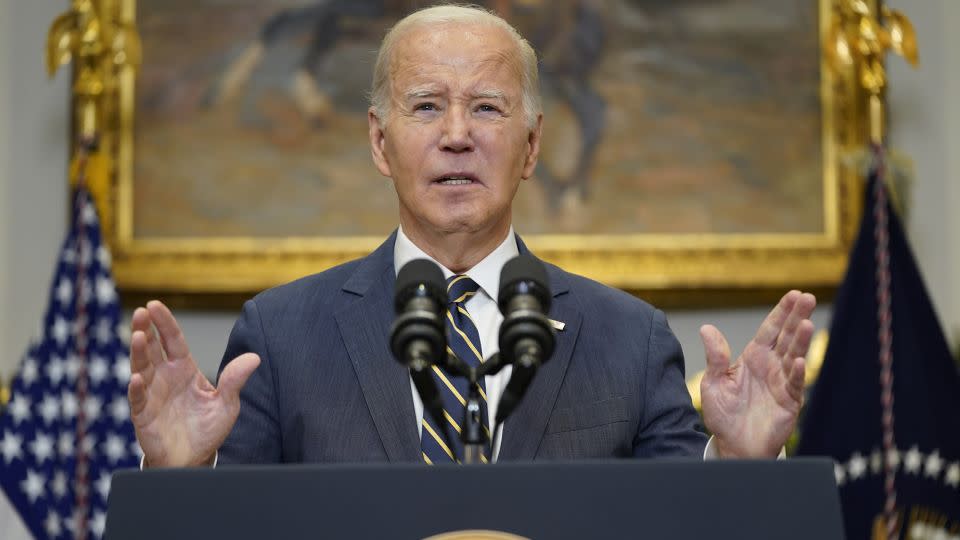

In an attempt to break the impasse, US President Joe Biden had appealed earlier Wednesday for Congress not to let “petty partisan politics” get in the way of aid for Kyiv. “History’s going to judge harshly those who turn their back on freedom’s cause,” the president said. “We can’t let Putin win.”

Britain’s newly appointed Foreign Secretary David Cameron was due to speak Thursday alongside US Secretary of State Antony Blinken in Washington, as the United Kingdom, too, urges continued international support for Ukraine as it battles Russia’s invasion.

The unity of purpose and intent - so remarkable for the first 21 months of Europe’s most consequential event since the fall of the Berlin Wall - had always been an outlier. More disarray and disunity looms.

In Washington, the uncertainty on display is more baffling. Congress’s reluctance to provide urgently needed aid is often billed as concerned Republicans not wanting to drag the US into another conflict. But the aid is meant precisely to prevent that: to ensure that Ukraine can keep fighting Moscow, rather than permit Putin to advance near enough NATO’s borders that the US is forced to fight for its allies in person, not via proxy.

A gentle blame game has begun, with extensive articles outlining why the Ukrainian counteroffensive failed to deliver the long-telegraphed results it needed. The Washington Post quoted anonymous US officials explaining Kyiv moved too late, or listened too little.

Ukrainian officials must still marvel at their allies expecting them to pull off complex military assaults minus the air superiority without which a NATO army would not even get out of bed.

It is a slow drain of vigor that Putin has surely long wished for. And it is a remarkable turnaround for an authoritarian leader who barely six months ago faced an open but short-lived rebellion from henchman Yevgeny Prigozhin.

Prigozhin is dead, killed with his other top Wagner figures in a mysterious plane crash. Moscow is rich on oil money. The prisons are filling the trenches with seemingly inexhaustible cannon fodder. Russia’s military has got back on its feet and has, for the most part, so far held back Ukraine’s counteroffensive – along with the billions of dollars of NATO training and arms that went into it.

The frontlines tell three tales. To the west, Ukraine has made a plucky - if hard to sustain - dive across the Dnipro River to create a bridgehead and threatens to attack Russia’s access to Crimea from the west. The nearby city of Kherson pays the price, shelled daily, and ghostly. Ukraine may see luck on this front, but will need a lot of it to make a difference and keep its forces resupplied.

To the center, the frontlines below Zaporizhzhia, for months the key focus of Ukraine’s attacks towards the city of Melitopol, are largely unchanged. A breakthrough here was the hope - the key result the West and Kyiv could have called a victory, cutting Russia’s mainland off from annexed Crimea - but it may not happen. The snows and darkness ahead will slow fighting further.

And to the east, a more troubling rhythm is forming around the town of Avdiivka. Of little strategic value, it is a symbol of Russia’s limitless tolerance of pain and casualties to achieve a basic, grinding victory. Its forces are slowly surrounding the town, much like they did with the city of Bakhmut earlier this year. They may take it, and lose thousands doing so. And the fear is that this is how they will move forward, throughout Ukraine. One tiny, costly victory at a time.

The biggest advantage Putin has is a West out of ideas - an alliance which saw its main strategy with Kyiv fail, and now thinks that more-of-the-same aid is essentially futile as the war cannot be decisively won.

Soon, Putin may appear more amenable to negotiations, and Europe may nudge Kyiv towards them for peace of mind. Yet this is despite most Western leaders being acutely aware that Putin cannot be trusted, and that Moscow uses diplomacy as a useful trick to advance its military aims. Any peace deal might last just long enough to allow Putin to refit, re-equip and then come back for more of Ukraine.

A victory in the US presidential election next year for Donald Trump would throw into this highly dangerous mix for European security a US president with an inexplicable fondness for the Kremlin head. Trump boasts he could forge a peace deal in Ukraine within 24 hours. He will be lucky if it even lasts that long.

So where do we go now? What does Ukraine do? First, the West must drop its fear of a humiliated Russia. Putin has shown - after attacks on the Russian mainland, a failed coup, and multiple ships in his Black Sea Fleet upping sticks to the safety of Russia’s main Black Sea coast - that he is not interested in escalation. He is struggling to defeat his weak neighbor and cannot take on NATO in full. The same goes for nuclear war; Putin has shown he is a pragmatic survivor, not a madman bent on global apocalypse.

Second, the West must arm Ukraine to the full – and fast. The approach of supplying a slow drip of weapons has proven catastrophic: the US Army Tactical Missile Systems (ATACMS), the M1 Abrams tanks - they arrive, but too late to make much difference.

Third, the West must make it clear that no peace deal with Russia can let it maintain a land corridor across southeastern Ukraine between the Russian mainland and Crimea. That will deny Moscow of something it can call a strategic victory.

But most importantly, Europe and the US must retain the conviction this is an existential fight for Western security. Upon its outcome rest China’s ambitions towards Taiwan, NATO’s own border security, and permitting a leader indicted for war crimes -to get away with it.

Putin cannot win, or else the price will be paid perhaps not only by this generation, but those to come.

For more CNN news and newsletters create an account at CNN.com