Westinghouse robot Elektro's ownership in limbo

The fate of Mansfield's world-famous robot Elektro remains in limbo following the closure of the Mansfield Memorial Museum on July 4.

Is Elektro going to the Henry Ford Museum in Michigan or was Elektro donated to the Mansfield Memorial Museum for permanent display? That question may have to be answered in probate court.

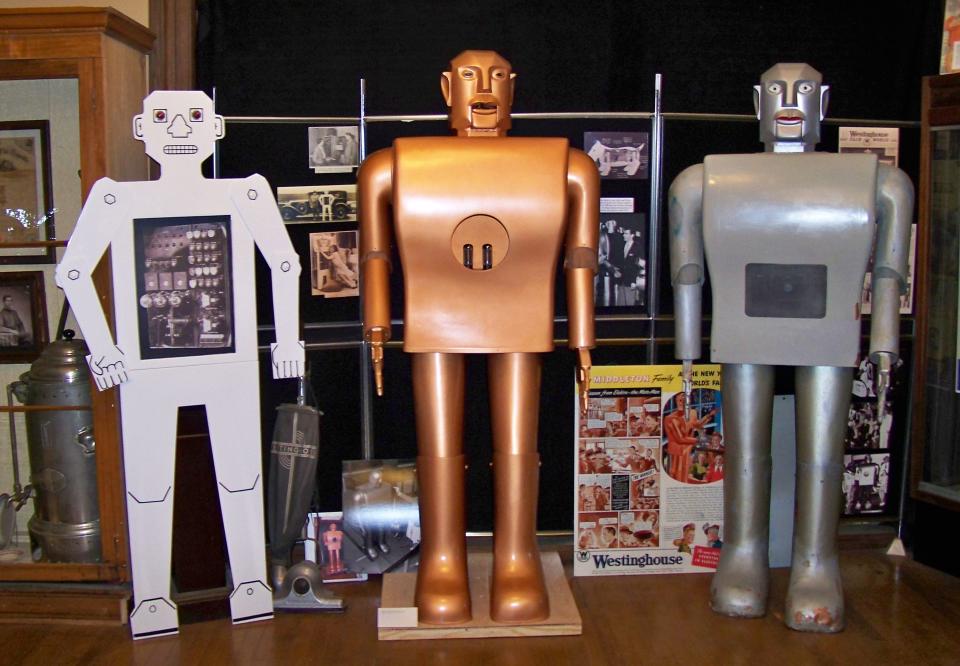

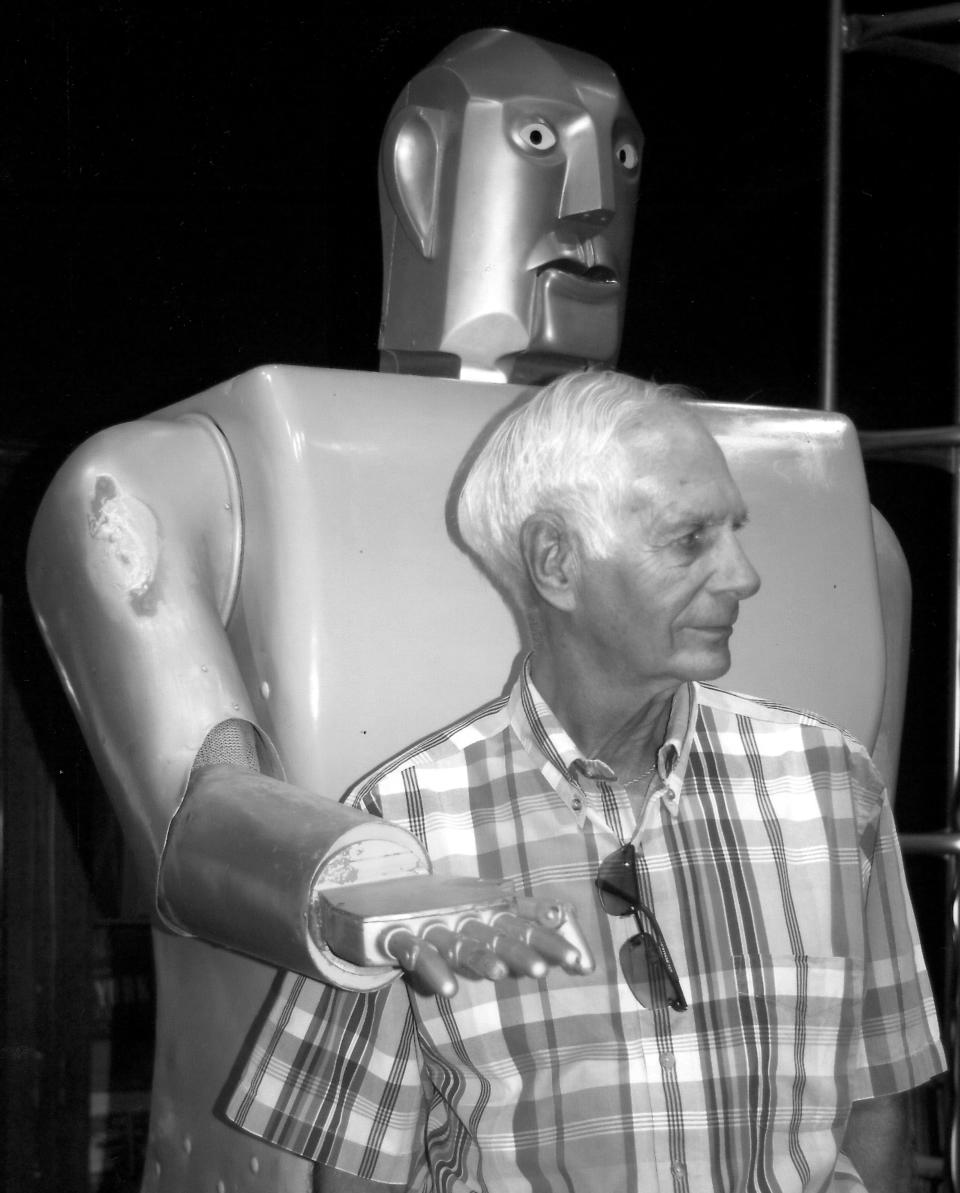

In 2014, people gathered at the museum to celebrate Elektro’s 75th birthday. Known as the oldest surviving robot in the world, Elektro was built at the Mansfield Westinghouse Appliance Division plant for the New York World’s Fair in 1939.

The late Scott Schaut, director/curator at Mansfield Memorial Museum, made a traveling replica of Elektro that could be rented for special events to institutions. The original is on display permanently at the museum, Schaut had told the News Journal.

"Their goal from the beginning was to have a human-form robot like Elektro in every person's home as a helper," Schaut told the News Journal in 2019.

Elektro could walk and talk and even smoke a cigarette, bringing delight to the tens of thousands who watched him in action during the World's Fair.

Then came The Great War, which forced Elektro into hiding for nearly a decade until the economy of the United States was again ready to embrace the allure of a robot-assisted world.

Schaut, who died July 4, also told numerous people the robot would remain at the museum until his death, after which it would go to the Henry Ford Museum in Dearborn, Michigan.

A representative of the Weeks' family who donated Elektro to the Mansfield Memorial Museum said this week that the original robot was meant to stay in Mansfield.

John Weeks came to the museum Monday afternoon and brought a notarized affidavit signed by his late uncle Jack Weeks, who found the robot and put it back together.

John Weeks, of Hoover Instruments in Mansfield, said his grandfather by the same name John was an engineer at Westinghouse who helped build the robot with another Westinghouse employee, Harold Gorsuch.

"He (his uncle) donated it to the museum with the intent it stay here in Mansfield," John Weeks said to Ed Olson, the museum's board president. The copy of the affidavit was notarized and signed on March 18, 2014. Elektro was transferred by truck to the museum in 2004, having spent a number of years in the Hoover shop and homes of past owners.

Weeks said his uncle's original affidavit says Elektro was going to stay at the museum until the museum no longer wanted it. It could not be sold, the affidavit said.

"The family, really, Jack's children and ex-wife ... It doesn't belong in anyone's living room. It needs to be here in town for people to enjoy it and the grandkids can come and see it. In their opinion and our opinion it belongs here in town. Where, I don't know," Weeks said.

Partial inventory of museum items to be filed in probate court

Since Schaut's death this summer, a handful of people and organizations have contacted the museum about ownership of items in the museum, Olson said. Malabar Farm Foundation, Mansfield Fire Museum and the Sons of Union Veterans have questioned the ownership of some donations.

Olson shared a story Monday about how ownership of some items is being challenged. A grandmother who made a doll for her sister, a Navy Wave doll, during World War II, and the doll was donated to the museum but a granddaughter has come forward claiming it as hers. Olson said he made a notation in the inventory provided by Schaut.

Olson said anyone who questions any items listed in the museum's inventory as being part of Schaut's personal collection needs to file a claim with the Richland County Probate Court as soon as possible.

The Schaut estate is moving forward with plans to hold an auction of the items listed as Schaut's in that inventory with Whatman Auctioneers.

Attorney says Elektro's ownership may be determined by probate court

Mansfield attorney Cassandra Mayer, who represents Schaut’s estate, said work continues on the Schaut inventory list at the museum.

“As we’re going through those right now, the museum is making decisions as well as to what they want to continue to have the museum be about.

“Right now the information I have about Elektro is, I have an affidavit that was signed while Mr. Weeks was still alive indicating that it was his intention when the museum was finished with Elektro to have it go to a museum in Michigan, the Ford museum,” Mayer said. “My understanding is there may be other family members, now that he has passed away, that have indicated that they would like to see it here locally at another museum, the North Central Ohio Industrial Museum. My understanding is some of the family would like it to go there.

“We’re still going through the museum. That may be something that has to be looked at, at probate to determine who the actual owner is,” she said. "I have information from some individuals and I would welcome other ones who claim that Mr. Schaut was holding some of their items to contact my office about that. I’ve had some contact about that,” Mayer said.

She said Elektro’s future site and ownership may be a probate issue.

“A partial inventory will be filed with the court in the next couple weeks,” Mayer said. “We have to have our inventory approved before there is a sale."

She said she will keep the local community apprised of any auction date or online auction. She said Micah Leeth is serving as the estate’s expert appraiser.

Museum board president wants confirmation, not confrontation

Olson said under the advice of the board's attorney, Don Hoover, until everything is worked out, nothing should leave the building. Only two people have keys to the building and all locks and codes have been changed, Olson said. Museum trustee Lori Fourhman is in charge of verifying the items on the inventory list.

"Under the advice of our attorney, we are to protect and preserve all the artifacts in the museum until such time as the probate court directs what is to be done with it," Olson said.

"This could take multiple weeks or several months, he added.

"So if somebody were to say, 'I heard Elektro is going to Michigan.' Elektro is going to sit right there until there is a final disposition and that's where these affidavits come into play," Olson said.

"Nobody is looking for confrontation. We're just looking for confirmation as opposed to confrontation," Olson said.

Olson was asked by Jerry Miller, who is the director of the North Central Ohio Industrial Museum, just how the board knows if Schaut paid for the items on his inventory list, such as an extensive Westinghouse appliance collection that David Howat from Vermilion donated to the museum.

Olson said he doesn't know the answer.

"Many personal collections are assembled over decades," he said, using the example of a Barbie doll collection. "When somebody is trying to have a complete collection of all the Barbie dolls which were ever made from 1959 onward, they may or may not have kept a receipt. They may have bought one at a garage sale.

"Don (Hoover) said one of the problems you have, to answer your question, in my personal opinion, it's nearly impossible to say with any definite knowledge what beyond the shadow of a doubt was his personal property," Olson said.

"The only thing I can say is I think the onus is on the estate to go through whatever paperwork he might have at his house and see if you find any personal receipts to see if you can prove this," he said. "I'm not being critical and I'm not saying anything ill of the dead. My kids for example will come to my house and say where did this come from? And I will say that was my grandfather's. There's no evidence to that effect other than the fact I remember it. I remember my father saying his father gave it to him."

Olson said there are forms for donations and loans used over the years when someone wanted to loan something to the museum. Schaut made a typed, single-spaced, 67-page inventory after Olson became museum board president. Olson said Schaut made the inventory list after he told the museum curator that if died in a car crash and if there were no existing inventory at the museum, no one would know what belonged to whom.

"I said without an inventory, your entire personal collection belongs to the museum," Olson added. "That did get his attention and within a few months (he made the inventory)."

What's the fascination with Elektro?

“You have to remember, there were no computers in 1927, 1931, 1939, except massive things. Everything was run by voice command on Elektro. He’s made of vacuum tubes, photo-electric cells, telephone relays,” Schaut previously told the News Journal. “His brain is actually not inside him. It’s behind stage.”

Schaut explained that as the operator spoke into a microphone, and the voice would go not into Elektro but into the control unit, which at this point has not been found, the News Journal reported earlier.

Mansfielders first got a sneak peek of the historic 7-foot-tall robot on April 21, 1939, before it was transported in pieces and reassembled at Westinghouse’s Pittsburgh headquarters for the official unveiling. By a mechanical quirk of fate, his first words in front of a large crowd and the company president were, “Be quiet. I am talking.”

In the past, Schaut said those few words made headlines across the globe: “Defiant Westinghouse robot tells CEO of Westinghouse to shut up.” Elektro wasn’t fired, Schaut said, and he went on to amaze millions of visitors to the World’s Fair for two years.

Schaut, in his four-page will, requested that any cats he may own at the time of death go to Stop the Overpopulation of Pets (STOP) on Lexington Avenue, along with $10,000 in cash.

"I give and bequeath to my friend, Mary Judith Rissover, her choice of one item of my personal property, absolutely," the will stated. Schaut also bequeathed all real estate to Rissover, according to his will on file at Richland County Probate Court.

"I direct that all the rest of my personal property, household furniture, household furnishings, automobiles, books, clothing, jewelry, and collections located in my home and any property belonging to me and housed and/or displayed at the Mansfield Memorial Museum at the time of my death be sent to auction at Cowens or any other large auction house outside of the north central Ohio area, for auction, as deemed appropriate by my executor.

"I request that all proceeds of the auction be given to the Milwaukee Humane Society, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, in the name of my mother, Charlotte M. Schaut," his will said.

lwhitmir@gannett.com

419-521-7233

X (formerly Twitter): @LWhitmir

This article originally appeared on Mansfield News Journal: Scott Schaut said to many people Elektro going to Henry Ford Museum