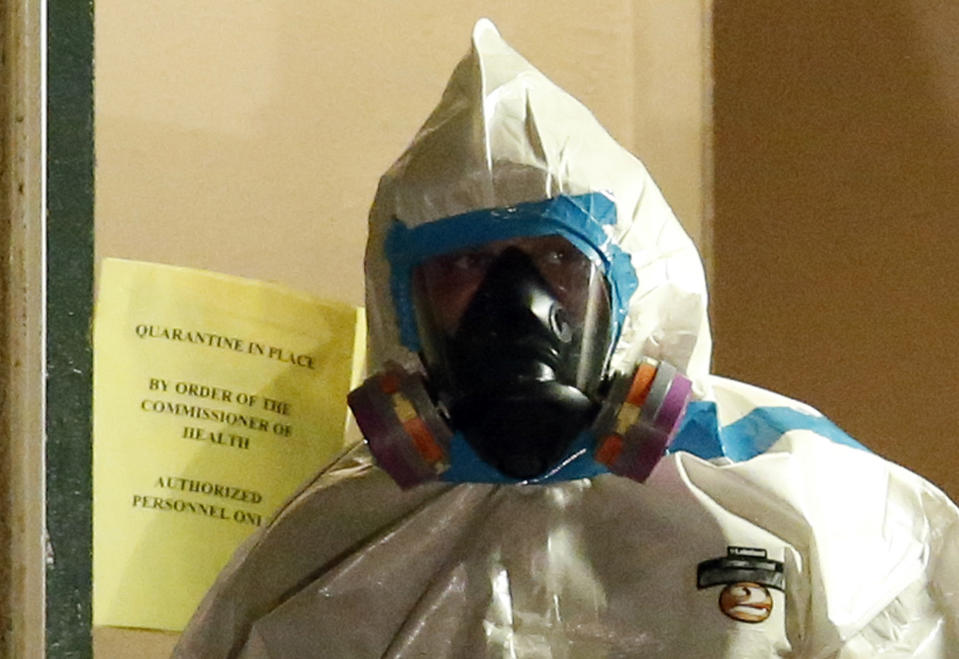

What it's like inside an Ebola protection suit

Sweaty on the inside, while keeping deadly pathogens on the outside

The sight of doctors in yellow-and-white protective suits is becoming familiar to those around the world watching health workers scrambling to stop the spread of Ebola.

So what is it like inside one of those biohazard suits?

"It's like being in a steam room," Dr. Joseph Fair, a virologist with the Merieux Foundation and special adviser to Sierra Leone's health ministry, told NPR in a recent interview. "You can imagine working in a room where it's [98.6 degrees]. ... So wearing that in the heat and humidity of Sierra Leone, combin[ed] with a mask and boots and goggles and the gown and everything else that you're wearing, it's an exhaustive process. I mean, just the amount of sweat that you have in the suit."

"They're suffocating," Armand Sprecher, medical adviser to Doctors Without Borders, said in July. "If you wear something very fluid-resistant, it's also very air-resistant. It's hotter than hell."

Fair, who testified before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee about the outbreak last month, says the exhaustion is exacerbated by too few people to help.

"You don't have enough staff, and so really it's hard to take a break — a bathroom break, a food break, a water break — because every time you do that, you have to completely disrobe, completely disinfect yourself, and then do the whole thing over again," he said. "Fatigue is a big problem. And so [there might be] just a little slip-up, such as maybe having an itch on your nose, and accidentally after 10 hours of work scratching your nose and moving the mask enough to where you've contaminated yourself."

The suit, in other words, is not foolproof.

"To work, it has to be used in conjunction with a set of behaviors and procedures," Sprecher said. "Where we see health care worker infections when [the suit] is in place, [the worker] did something to override [the suit]: They didn't wear it appropriately or contaminated their hands in the process of getting [the suit] off."

Sierra Leone, where Fair has worked for more than 10 years, has been one of the hardest-hit countries in West Africa. According to the World Health Organization, there have been 2,437 reported cases of Ebola in Sierra Leone and 623 deaths since the outbreak began in March.

"The outbreak will eventually come under control," Fair said. "But I do believe it is going to become worse before it gets better. And I think the next three months are going to be a very trying time; we still are seeing increases in numbers."

Among the most pressing needs are "supplies of personal protective equipment" — and body bags.

"We've run out of body bags more times than I can count," Fair said, "and not having a body bag leads you to not bury a patient for however long you don't have that body bag."

Related video: