Whatever happened to Richland’s plan to build a 3rd high school to ease crowding?

West Richland might not get its own high school for at least another decade.

New demographics provided to the Richland School District show that enrollment isn’t growing as rapidly as it was before the COVID pandemic.

So a new third comprehensive high school — with a current price tag of at least $255 million — might not be needed until 2035.

As a result, the Richland School Board has decided to forgo asking voters anytime soon to approve an estimated $300+ million bond measure.

Instead, it will likely consider pitching a spree of smaller bond packages over the coming years to ease crowding, improve school security and replace aging facilities.

“I think it was a smart decision to wait and see,” board President Rick Jansons told the Tri-City Herald.

“It’s important to wait and rebuild public trust in the years after COVID and have this conversation with our constituents rather than rush to a quick decision,” he said.

Instead of a bond, Richland voters last year approved a six-year, $23 million capital improvement levy for school security upgrades and to begin the planning process for a third high school.

In Washington state, bonds are for building schools and facilities, while levies are for paying for learning and education programs.

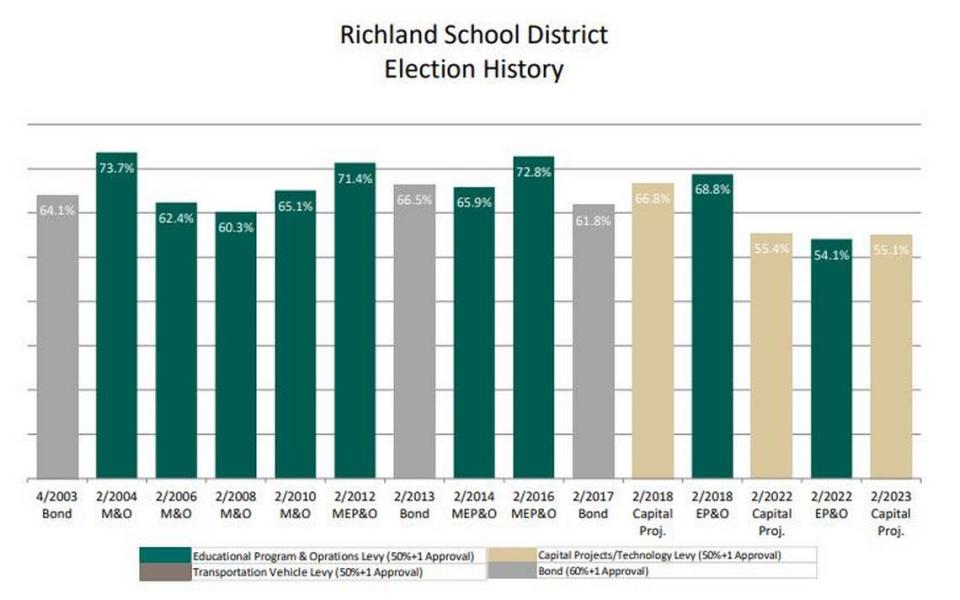

Unlike levies, bond measures require a 60% “super majority” of voters in the district to pass. Local school districts share the burden of paying for the construction of new schools and facilities with the state, which provides matching dollars.

The school district has had its eye on building another high school for at least a decade now.

In 2016, the district bought 70 acres near the intersection of Belmont Boulevard and Keene Road in West Richland for the project.

The delay means the West Richland students will continue to be bused to high schools in Richland.

The delay in pursing it now is in stark contrast to how the district has framed the need to ease crowding at Richland High School and Hanford High School. Just over a year ago, the district hoped to break ground on the third school in summer or fall of this year.

District officials previously said the new school would open up more curricular and extra-curricular activities, including sports programs, for students in one of the state’s fastest growing communities.

But facilities planning remains an “ever-changing landscape,” Superintendent Shelley Redinger said.

She said they’re constantly considering a myriad of variables — including enrollment, inflation, property assessments, overall economy, building costs and community input — when deciding where, when and how to build new facilities.

“Before the pandemic there was a lot of energy behind getting a new high school, and we were growing so significantly. Since the pandemic, we’ve really leveled off. The (enrollment) growth has slowed quite a bit. We’re not declining, but we are slowing quite a bit,” Redinger said.

The school board — which has three new members following last year’s historic recall vote — plans a workshop Thursday, Jan. 11, to discuss future bond planning.

Voters across Washington state have been declining bonds and levies at a higher rate since the pandemic. Support for school measures, once thought to be as solid as a rock, has declined as voters face higher a cost of living and with sentiments around public schools changing.

More than a dozen school districts across the state tried passing construction bonds last year. But only two met the voter threshold required for approval — South Whidbey and Pasco.

Pasco’s third comprehensive high school is currently under construction at 6091 Burns Road. It will open to students in Fall 2025.

Richland has a squeaky clean record of passing school measures. Over the last two decades, it has passed every bond and operating levy it presented to voters.

Overcrowded schools

Students and staff at Richland and Hanford high schools are feeling the pressure of crowded hallways, packed classrooms and depleting programs space.

Hanford High School, built in the 1970s as a K-12 school and later renovated in the early 2000s, is designed to serve fewer than 1,700 students. About 1,975 are currently enrolled at the north Richland school.

Richland High School was built in 1943 and saw several additions and modernizations from the 1960s through the 1980s. It was also remodeled in 2008. The downtown high school was built to serve about 1,900 and currently serves about 2,200 students.

Enrollment there has risen so much in recent years that at least nine teachers aren’t able to conduct a prep period in their designated room because the rooms are needed for another class at that time, according to one architect’s report to the district.

Hanford’s pressure points have been on certain departments, specifically the arts, photography and broadcasting.

Redinger said they have enough high school enrollment to fill a third high school, which if built today would bring enrollment at all three high schools down to about 1,700 students each.

But that’s not her call — it’s up to the community and school board, she said.

“Really it comes down to having these conversations with the community about these next steps,” she said.

The delay would require a number of changes to ease crowding, however.

Hanford’s campus has plenty of land that could be used for modular buildings or portables.

The district could also allocate space in other new buildings for high school education programs.

School officials also are considering replacing River’s Edge High School’s portable classrooms with a modernized two-story building that would also house Pacific Crest Online Academy. More students could be moved from the comprehensive high schools into the alternative learning building. River’s Edge’s enrollment could more than double, from 150 to 400 students.

“I think the primary goal of the board is to figure out what facilities are needed to support student learning,” said Jansons, adding that the board’s new members are going to be more open minded about the proposals and will work to prioritize student needs.

Future bond projects

School board documents show the district could run a succession of four small capital bonds over the next 25 years to replace aging facilities, make school security upgrades and address overcrowded buildings.

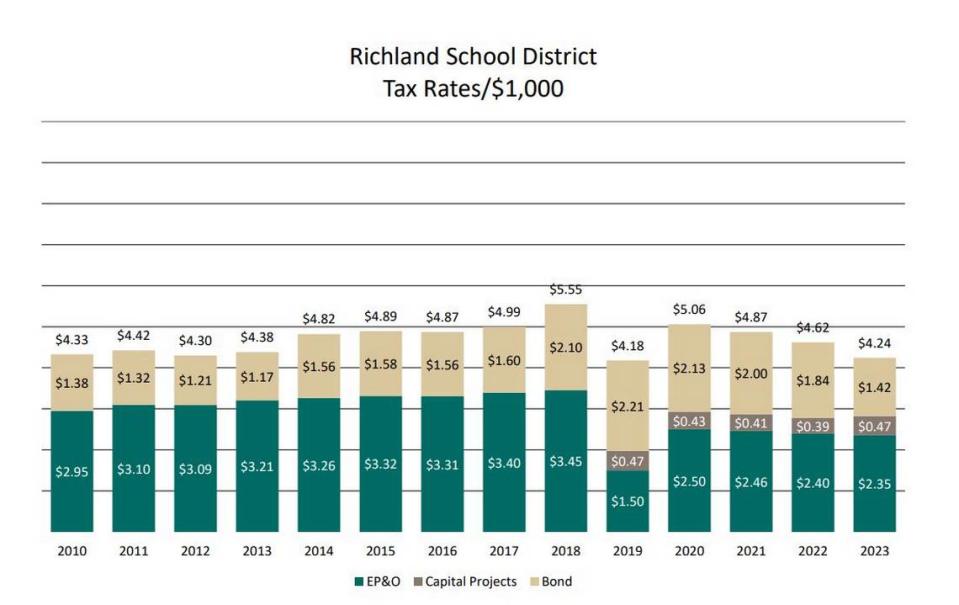

“One of the things about doing bonds every four to seven years is that, as old bonds are paid off and new bonds are added on, it keeps the tax rate flat and predictable,” Jansons said.

Here is a proposed list of some of the larger needed projects that the board expects to consider in the coming years. No dates have been given on when the bonds requests could go to voters.

Bond 1

Hanford High flat roof replacement: $4 million

Three Rivers HomeLink expanded educational spaces: $10 million

New building for River’s Edge High and Pacific Crest Online Academy: $45 million

Hanford High upgrades to athletic stadium and theater scene shop: $16 million

Education and Operation Center: $89 million

Sod practice field for Richland High-Carmichael Middle students, and Fran Rish signs: $4 million

Capital projects levy cancellation: $23 million

Bond 2

Safety and security upgrades: $5 million

Modular classrooms for Richland High and Hanford High: TBD

Early Learning Center in West Richland: TBD

Richland High new multipurpose room: $5 million

Indoor lap pool: $20 million

Bond 3

Chief Joseph Middle replacement: $75 million

Carmichael Middle replacement: $75 million

William Wiley Elementary replacement: $47 million

New elementary school in south/west Richland: $47 million

New middle school in south/west Richland: $75 million

Bond 4

New third comprehensive high school: $255 million

Enhanced stadium and theater at third high school: $22 million

Various turfing projects: $9 million