What's behind Warren's plan to break up Facebook, Amazon and Google

Presidential elections are decided by many things: media exposure, financial backing, personal chemistry, timing and luck. Policy positions often are just a way of signaling where a candidate stands on the political spectrum. But 2020 is shaping up to be different, the most ideas-driven election in recent American history. On the Democratic side, a robust debate about inequality has given rise to ambitious proposals to redress the imbalance in Americans’ economic situation. Candidates are churning out positions on banking regulation, antitrust law and the future effects of artificial intelligence. The Green New Deal is spurring debate on the crucial issue of climate change, which could also play a role in a possible Republican challenge to Donald Trump.

Yahoo News will be examining these and other policy questions in “The Ideas Election” — a series of articles on how candidates are defining and addressing the most important issues facing the United States as it prepares to enter a new decade.

Internet behemoths Amazon, Google and Facebook have become frighteningly dominant, their growth uncontrolled, their practices too often secretive and dodgy. Between swallowing competitors, expanding far beyond their original missions and spying on consumers, these super-platforms are growing too complicated for the government to fully understand and effectively regulate — or so it appears.

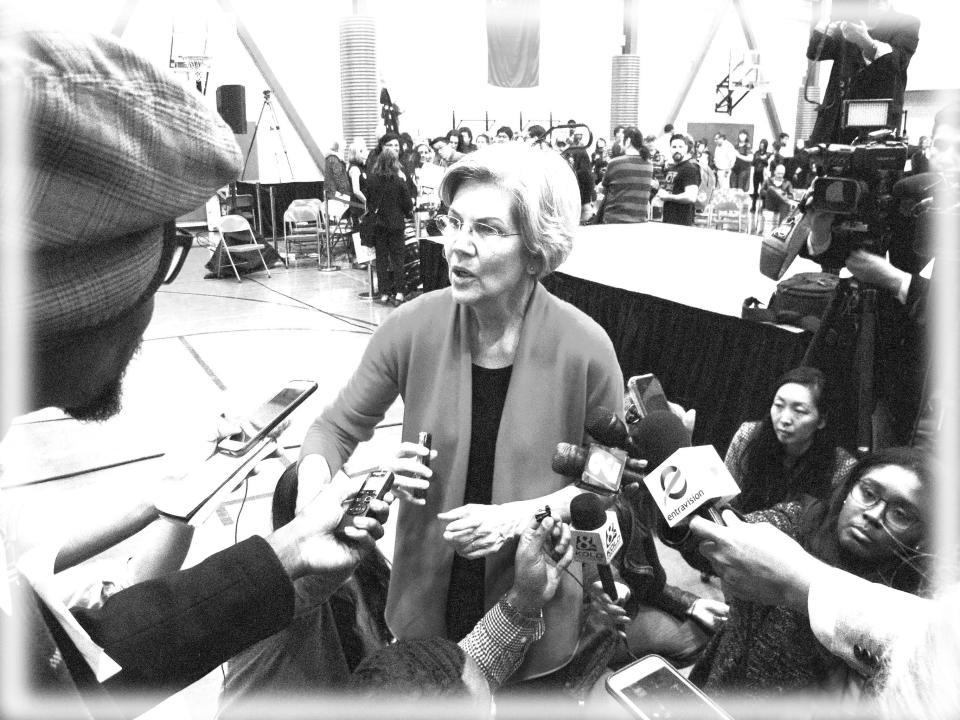

“We have these giant tech companies that think they rule the earth,” 2020 Democratic hopeful Sen. Elizabeth Warren told supporters last month in Long Island City, the Queens, N.Y., neighborhood where Amazon, courted with municipal favors, earlier announced that it would open a second headquarters — plans it abandoned in the face of protests about the size of the tax break the city and state had offered to lure the company. Warren accuses Amazon and other tech giants of unfairly demanding special favors from governments, selling users’ consumer profiles for marketing purposes and exercising a stranglehold over capital funding for potential competitors.

Twenty-five years ago, back when dial-up modems hissed and sputtered to launch us onto “the Net,” few imagined that a handful of startups, with businesses largely not understood, would evolve into global monopolies as all-pervasive and powerful as the 19th-century industrial trusts.

The most impressive of these trailblazers is Amazon.com, the online bookseller turned general retailer that went live in 1995 and is now the country’s second-largest private employer. With a platform that accounts for nearly half of online sales in the U.S., it registered $232 billion in revenue in 2018. Its profitable Amazon Web Services (AWS) dominates the cloud storage arena, including newly created “secret regions” for all 17 U.S. intelligence agencies. Now fulfilling the vision of founder Jeff Bezos, the world’s richest person, of becoming “the Everything Store,” Amazon has revolutionized society with novel technologies, from the e-reader Kindle to the talking home assistant Alexa, which keeps track of appointments, commands other household appliances and can even tell jokes. Like Amazon itself, which is running secret medical labs, Alexa is moving into health care, with the home assistant being programmed to monitor blood-sugar levels and oversee patient health records. Amazon puts robots to work in selected warehouses and promises that drones will soon deliver our goods; it’s even moving into outer space, with plans to launch satellites to increase internet coverage for billions of unconnected potential consumers. And, after a spate of mergers, it now owns Whole Foods, Zappos, PillPack, IMDb, Goodreads, AbeBooks and dozens of other companies, some having been allegedly forced into “shotgun marriages.”

Warren is alarmed at how the hydralike company keeps sprouting new appendages. She’s particularly concerned by how, in its role as a marketplace for third-party vendors, Amazon uses information collected from those sales to promote its own slashed-price product line, Amazon Basics, which it often gives top billing on its vendor pages.

Google too has charted new territories all over the internet map, including by jumping into mapping. Merely a web browser when it launched in 1998, Google’s parent company, Alphabet, now operates Gmail, Google Analytics (an online marketing data service), Android, Chrome and YouTube — 41 services in all, with seven of them boasting over 1 billion users. Its most lucrative arm is ad sales — which brought in over $116 billion for the company last year. With its vast database of our browsing habits, Google is believed to have more consumer data than any other company. And while it claims not to be selling that information, companies that advertise with Google are provided with key insights, including details about where traffic to their sites originates.

Once an innocent means to keep up with friends, social media monolith Facebook has monetized its user base through ad sales, delving into telephony, messaging and more, becoming an omniscient data conglomerate that took in net revenue of over $55 billion in 2018. Like Google, it uses algorithms to decide what to show users based on previous “likes” and engagements. As one of the most popular sources for Americans to get political news, it’s arguably a media platform, and certainly an advertiser’s dream. With precise demographic targeting that is also well-suited to propaganda, it became a venue for Russian agents to run anti-Clinton, pro-Trump ads and posts. Data harvester Cambridge Analytica, which worked on the Trump campaign, nabbed detailed info on 87 million Facebook users through an app. Facebook tries to engulf the competition too, recently buying WhatsApp and Instagram. But whatever one thinks of it, founder Mark Zuckerberg insisted during congressional testimony that there’s one thing Facebook isn’t: a monopoly.

Warren disagrees: she calls Facebook, Google and Amazon “high-tech monopolies” in her article posted on Medium.com, saying they have too much power “over our economy, our society, and our democracy. They’ve bulldozed competition, used our private information for profit, and tilted the playing field against everyone else. And in the process, they have hurt small businesses and stifled innovation.”

Concerns about companies growing too big and controlling their market date back to the 19th-century robber barons, when railroads, oil companies, steel companies, even sugar companies and beef packers, became untouchable giants, fixing prices, bribing, buying up and killing competition along the way. The Sherman Act of 1890, designed to rein in monopolies, wasn’t given teeth until Theodore Roosevelt’s administration, when the Justice Department sued to dissolve a railroad merger and took on the six largest meat packers over price fixing.

In 1911, the Supreme Court took the bold step of ruling for the breakup of John D. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil, smashing it into 34 separate corporations.

Antitrust action entered the electronic age in 1982, when the line was cut on telephone giant AT&T, which was broken into eight so-called Baby Bells. Since that time, antitrust actions, which typically focus on “consumer welfare” — i.e. prices — rather than corporate size as such, have mostly fizzled. The government case against Microsoft, which was accused of unfairly competing with web browser Netscape, prevailed briefly, when a court ruled that the software giant had to break into two companies. The next year an appeals court reversed that order. Microsoft did, however, settle with the government, and its stranglehold on browsers was effectively broken.

The digital landscape has become more complicated since then, and legislators haven’t always kept up. (As late as 2006, Sen. Ted Stevens of Alaska, who headed the Senate Committee on Commerce, Science and Transportation overseeing digital technology, famously described the internet as “not a big truck” but “a series of tubes” prone to clogging.)

Today’s lawmakers appear savvier, but haven’t yet taken strong action, unlike in Europe, where the European Union is cracking down hard. It recently fined Google nearly $10 billion in three cases for anticompetitive behavior, including favoring its own advertisers by putting them first in its search results. The EU is considering slapping a fine of up to $2.2 billion on Facebook for the platform’s “toxic content” and privacy breaches, and it is investigating Amazon for antitrust practices as well. After publishing a report in February calling Facebook “digital gangsters,” the British government just days ago announced it is considering creating an internet regulator to oversee Facebook, Google and other mega-platforms, with an eye toward controlling disinformation and violent content. But in the U.S., no new laws have been passed, even though Congress has called in the heads of high-tech companies to testify on privacy breaches and anticompetitive behavior. These ever-changing companies operate and expand without much U.S. oversight or restraint because U.S. antitrust law focuses on protecting against price-gouging — and Facebook and Google, obviously, are free, while Amazon’s impact on the marketplace has mostly been to make products cheaper.

Regulatory oversight may be beefed up if Warren gets her way, though initially, one couldn’t read about her monopoly-busting proposals on Facebook, which immediately took down her ad. After the removal made headlines, platform administrators reposted it, explaining that it was taken down because it displayed Facebook’s logo.

Warren’s plan has two parts. First, it focuses on tech companies and platforms with more than $25 billion in annual global revenue, designating them as “platform utilities” and divested from companies that sell on that platform. Amazon, for instance, would be required to break off from Amazon Basics, which has been accused of predatory pricing and hardball tactics against competitors such as Quidsi, the company that owned Diapers.com. Amazon’s bargain-basement pricing of its own baby products compelled the owners to sell the company to Amazon in 2011; six years later, Amazon tossed it away like a worn nappy.

“You can be an umpire or you can own teams,” Warren explained. “But you can’t be an umpire and own one of the teams that’s in the game.” She believes that fear of her proposal has inspired Amazon to change some practices, deemphasizing Amazon Basics on vendor pages.

Second, Warren would assign investigators and regulators to unravel these companies’ anticompetitive acquisitions. The big three have snatched up more than 400 companies in recent years. These investigations could force them to divest. Facebook, for example, would be scrutinized for its purchase of WhatsApp and Instagram, while Amazon might have to bag Whole Foods, which it gobbled up for $13.7 billion in 2017, or kick off shoe retailer Zappos, which it slipped into back in 2009.

Last Wednesday, Warren introduced a bill in the Senate that would bolster enforcement powers: Though not aimed specifically at tech companies, under her proposed Corporate Executive Accountability Act, negligent company bigwigs could be criminally charged and face jail time if their company “is found guilty of a crime or is found liable for a civil violation affecting the health, safety, finances or personal data of 1 percent of the U.S. population or 1 percent of the population of any state.”

Both Republicans and Democrats cheer and jeer Warren’s proposal in nearly equal measure; some commentators call it an “assault,” some hail Warren as a gutsy modern-day Teddy Roosevelt, others shrug her off as a “wrong-headed” populist dreamer, pitching a “fairy tale.” Among the criticisms is the fear that increased oversight would stifle the cheap pricing these firms now offer; others say her proposal doesn’t go far enough in tackling privacy lapses and other concerns. The most organized attempt to shut her down may come from Americans for Prosperity, the Koch brothers–funded advocacy group that is launching an ad blitz urging lawmakers not to politicize antitrust laws.

Yet cheers come from surprising corners: Sen. Ted Cruz, R-Texas, and Rep. Matt Gaetz, R-Fla., are among Republicans supporting it, as is Steve Bannon, who says he’s had similar ideas for years. Presidential hopefuls Sens. Bernie Sanders and Amy Klobuchar say they also want to confront big tech. Academic legal writer Lina Khan, whose 2017 article about Amazon and antitrust in the Yale Law Journal fired up the Federal Trade Commission, gives the Warren proposal a thumbs up, as does the antimonopoly Open Markets Institute. Polls indicate that Americans, by a narrow majority, don’t see the need for more regulation of internet companies, and a survey released last week showed a majority saying they believe the government should not interfere. Meanwhile, the Federal Trade Commission has announced it will boost efforts to investigate anticompetitive behavior, and several state attorneys general are promising to file antitrust suits against the giants, which might give the issue even more impetus going into the election.

Cover thumbnail photo illustration: Yahoo News; photos: AP

_____

Read more from Yahoo News: