What's it like to hear voices? NJ course aims to help police aid those in mental crisis

The voices were harsh, unforgiving — a constant stream of sounds with few breaths between sentences. Some words were barely distinguishable over a rush of muffled whispers.

Stand up look to the left don’t look up just look left NOT NOW not now don’t do that now. Stop. I said stop it. Would you stop? You know they know, you suck and they know it.

The internal monologue blared from 30 sets of headphones into the ears of Bergen County patrolmen, sergeants, sheriff's officers and police officers, as well as mental health professionals. They all squinted at a video clip projected on a large screen and scribbled on worksheets.

Their task: Try to answer questions about the video while listening to the disturbing mantras, a training that mimics what it’s like to experience auditory hallucinations. The 48-minute clip was created by Pat Deegan, a disability rights advocate who was diagnosed with schizophrenia as a teenager and went on to earn her doctorate in clinical psychology.

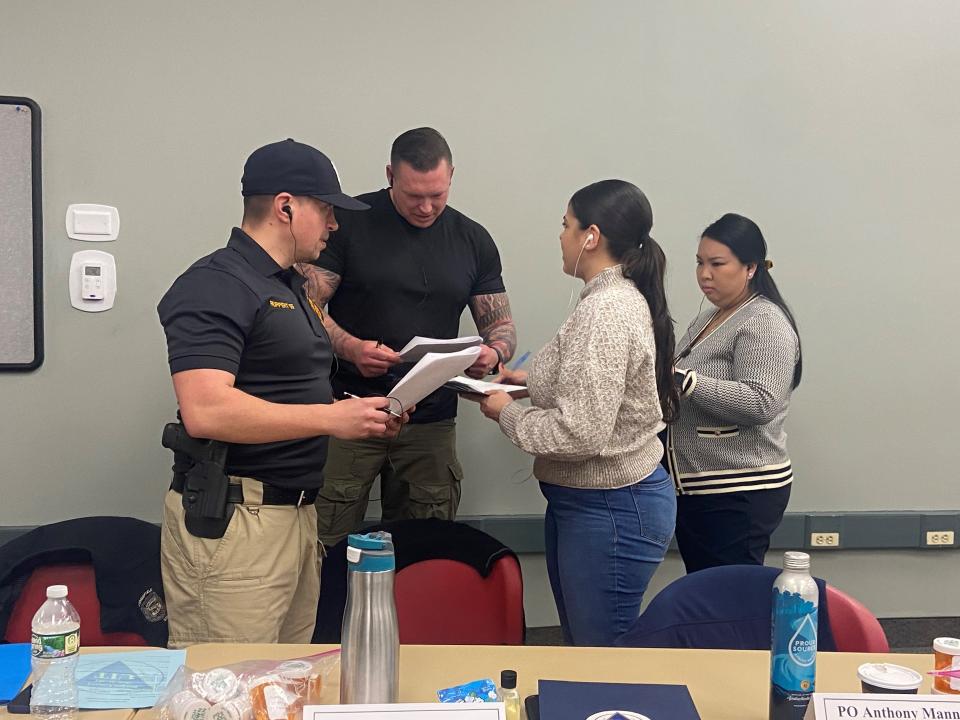

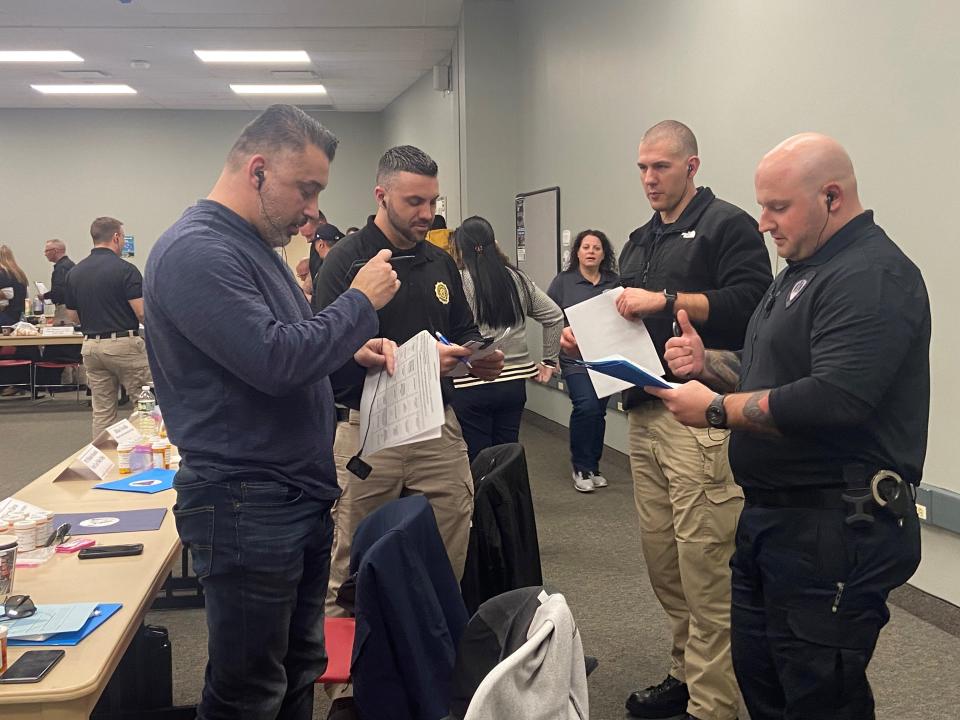

The immersion was part of crisis intervention team training held this month in Mahwah, a five-day, 40-hour class offered to law enforcement and mental health providers, designed to improve how they work together and interact with someone having a psychiatric crisis.

It’s among a handful of efforts governments are using to try to lead to safer interactions by teaching de-escalation techniques, reducing the stigma of mental illness, and encouraging empathy and understanding.

Training:Headlock? Taser? Gun? NJ police learn jiujitsu to restrain hostile subjects without harm

Suicide prevention:How one NJ woman pulled herself from the brink of suicide to a new mission

“All law enforcement and corrections should take this class. It should be mandatory,” said Cecelia Molina, a corrections officer with the Bergen County Sheriff's Office, who works in the jail’s mental health unit. “It would help people know how to properly communicate and understand mental health. I think shootings and use of force incidents would decrease tremendously.”

A majority of cases where New Jersey officers use force involve someone going through a potential mental health incident, according to the Attorney General's Office. New Jersey officers use force on a disproportionate number of Black people, a population that nationwide is killed at disproportionate rates by law enforcement.

Instructors want to stop tragedies like the March 3rd killing of 31-year-old Najee Seabrooks, a Black man and street shooting survivor who had worked with the Paterson Healing Collective’s violence intervention program. Seabrooks was shot by two Paterson police officers during a four-hour standoff with Seabrooks barricaded inside his home, having an apparent mental health episode.

Body camera footage has not yet been released. The president of the union that represents Paterson’s ranking police officers told the Paterson Press that Seabrooks moved toward the officers wielding knives.

Story continues below photo gallery

Civil rights groups and locals demand more than training. A coalition of advocates is urging the U.S. Department of justice to investigate the department, Black Lives Matter Paterson is calling for a complete restructuring of the department, and the Salvation and Social Justice group suggests a state takeover of the Paterson Police Department.

State program pairs police with mental health experts

Paterson police did not let members of the Healing Collective speak with Seabrooks at the scene during the standoff, and no one called St. Joseph's University Medical Center's "crisis response team" of behavioral health specialists who handle emergency calls involving people in mental health crises, the hospital CEO told NJ Advance Media.

In February, the state Attorney General’s Office announced expansion of the ARRIVE Together program, which pairs plainclothes officers with mental health experts to respond in unmarked vehicles to certain 911 calls, setting up partnerships in more than two dozen municipalities across 11 counties.

Departments in Bergen and Passaic counties are not currently part of the program. Gov. Phil Murphy proposed $10 million in next year’s budget to expand the program to the entire state.

Bergen offers mental health services dispatch

Bergen County offers emergency mental health services to those who call 262 HELP. Residents reach a CarePlus representative, who dispatches a mental health screener — ideally within 20 minutes, but it can take longer — who performs evaluations, crisis intervention counseling and support to those in crisis.

“In some scenarios, you hit a wall, and you don’t know where to go, and the go-to is always 262,” said Capt. Craig Casey with the River Edge Police Department. “But not everything falls under that, and sometimes we get help from 262 in 15 minutes, and then sometimes it’s, ‘We can’t have somebody out there until tomorrow.’"

Given all the resources and information provided by the crisis intervention training course he took last week, Casey said he wishes he had done it 25 years ago. "It would have made life a lot easier,” he said.

Those who take the course learn about active listening, laws around medical privacy, mental health screening laws, and warrantless entry from the prosecutor’s office. They role play use of force scenarios. They hear from mental health providers, the county homeless shelter, and other services that police can refer people to. At last week's session, speakers told harrowing stories about struggles with addiction and losing a loved one to suicide.

“The more people know about mental health and signs and symptoms and resources in the community, the more equipped law enforcement is to be able to make an informed decision on what's best for the person in crisis,” said Amie Del Sordo, senior vice president at CarePlus New Jersey and a licensed clinician who coordinates the mental health side of the training. “And if they can't, then they at least learn who they can contact to help them, which is key.”

Being more empathetic

More than 450 Bergen County law enforcement officers have gone through the crisis intervention training program since the county began offering it in 2016.

“It’s about being more empathetic, listening to people, taking your time,” said Sgt. Sean Flannelly, who signed up for the training after several officers from his force in Englewood Cliffs took it and “had nothing but positive feedback.”

Kristina Feliciano, a clinical manager at Bergen New Bridge Medical Center who comes from a family of police, said it’s important for the mental health and law enforcement worlds to understand each others’ roles.

“You can't jump in and just assume you know what's going on," Feliciano said. In most cases people with mental health crises are "very afraid and they're just acting out" because they see police officers in uniforms with their weapons, "and that's where they react. It's not like that in the hospital. In the hospital, they know that they're safe, and there's nobody there to feel threatened by.”

Understanding law enforcement's role

The course is also meant to show mental health experts the difficulties of law enforcement’s role.

“As a civilian, it gave me a different perspective of the job that [law enforcement] has to do in our community,” said Leidy Suriel, with the Bergen County Division of Mental Health and Addiction Services. “In all the role plays that we did, to see how they would de-escalate the situation, for me, that was like, ‘Oh wow.’ They were so calm and so respectful, and I really appreciated that. We need more empathy for the mentally ill community.”

After the video ended, classmates mingled about the room at Mahwah’s Bergen County Law and Public Safety Institute and filled out bingo cards, grabbing initials of people who love to read or hate football. The voices continued to drone on. Random splices of Soul Man by Isaac Hayes and David Porter faded in and out, like a radio with spotty reception.

Once everyone was seated, Lauren Salvodon, who led the exercise, asked, “How was it?”

“Very distracting,” Casey said.

“That was eye-opening for me,” said Molina, the corrections officer. “It made me really scared that it could happen to me, and I really feel for the people that suffer from schizophrenia.”

Salvodon said she speaks more slowly and extends her words to make sure that everyone wearing the headphones can understand what she’s saying.

“But in the real world, someone that has a diagnosis, you may not know it,” Salvodon said. And while the police may want to get the situation under control quickly, the person in crisis is "experiencing something that may cause delays.”

Juggling medications

On the first day of training, students received six orange prescription pill bottles each filled with Tic Tac mints, M&Ms and other candies, with labels “For: Clark Kent” or “Marsha Brady” and “Dr. Doolittle” listed as the prescribing physician. The trainees were instructed to bring the pill bottles back to class each day and eat the candies as instructed on the label — one of the "medications" was to be taken four times a day, another two times, and so forth.

Friday was the moment of truth.

“If you did not take your medication as prescribed, please stand up,” said Del Sordo, the CarePlus licensed clinician. “And if you do not have your medication, please stand up.

Twenty out of the 32 trainees stood.

The other 12 counted their remaining pills to confirm they had followed directions. There should be 25 once-a-day pills. Twenty-one twice-a-day. Seventeen three-times-a-day.

“It feels like complex chemistry,” someone said.

“Damn, I’m one short!” another man called out.

After cataloging all six medications, only four people remained seated.

"Try to put yourselves in our clients’ shoes and show a bit more compassion working with someone who says, ‘I forgot to take my meds,'" Del Sordo said.

Police Officer Kyle Ruppert said there are a few residents in Ridgefield who "will be fine for eight or nine months and then you see them again," and it’s clear they are not taking their medication.

“In your head, you’re like, ‘What, it's not that hard to take all this medication, and you know you have to do it because then it’s everyone’s problem,’” Ruppert said. “But seeing how difficult it was for 32 people to stay on track shows how much difficulty some people have to take all that medication. I’m always nice with them, but I know internally like, ‘Oh, this probably is not as easy as it sounds.’”

Trauma looks different for everyone

During the training, a series of speakers shared stories grappling with the trauma of losing a friend and a son, and wrestling with addiction. They spoke of difficulties seeking treatment — the stigma, lack of knowledge, and lack of financial help to do so — as well as the ways law enforcement and mental health practitioners fell short.

Wendy Sefcik told the trainees that she and her family had distressing interactions with law enforcement as well as mental health professionals and hospital staff in the years before her 16-year-old son TJ killed himself.

She called 911 during one fight she feared would turn violent between her husband and TJ. One officer “treated my husband and I like we were criminals,” and was “making everyone else fearful,” she said. The officer's partner took over the situation and calmed things down.

TJ continued to act out. He was uncharacteristically disrespectful, came home drunk and got in trouble for painting graffiti. The family took him to counseling. They were repeatedly told that he was acting like a typical teenager.

Then one day he wouldn’t get out of bed and was crying. They brought him to the hospital.

TJ was diagnosed with bipolar disorder and told to start three medications after staff observed him in a group session but didn’t speak with him. In his room, disturbing words were etched into the wall: ‘The only peace I will get is when I close my eyes for good.’ Sefcik removed him from the hospital against medical advice. Another doctor diagnosed him with clinical depression.

Six weeks into the school year, he took his life.

Sefcik is now the suicide prevention coordinator for Bergen County, and wonders if she knew then what she knows now if she could have saved her son.

“I think it’s really unfortunate that law enforcement is very often the first line for people struggling with mental health,” Sefcik told the trainees. “I think you need support. You should not be treating, diagnosing — but you should have a basic awareness.

“In the world of suicide prevention, sometimes the best thing to do is have open conversations and not be afraid to let people show their ugly," she said. "That’s why I share my story. Everyone that struggles with mental health doesn't have to necessarily come from dysfunction. Trauma plays a huge role, and what trauma looks like is different for everyone.”

This article originally appeared on NorthJersey.com: Course aims to help NJ police understand those in mental crisis