Here’s where Lexington is placing 100 Flock license plate reader cameras

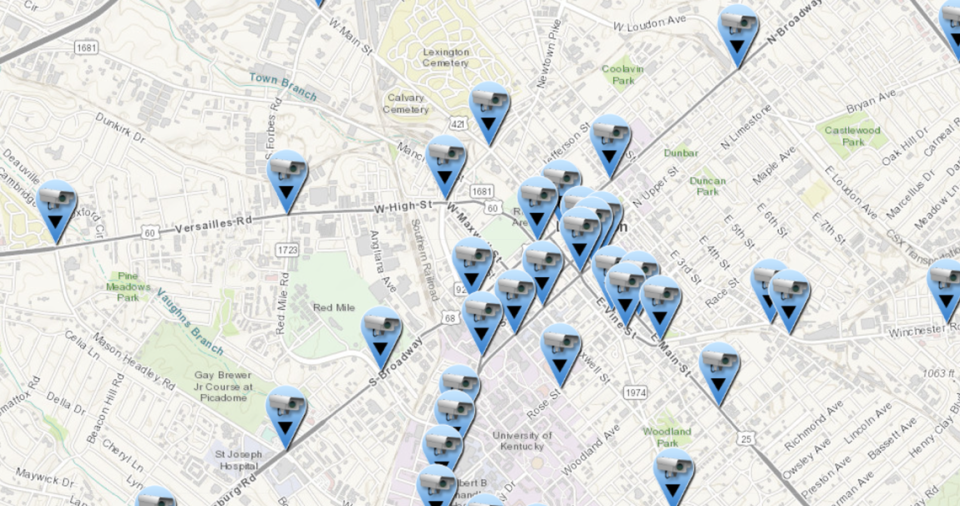

Lexington Police have released the locations of the city’s license plate reader cameras as it expands the number of cameras from 25 to 100.

Lexington Police Commander Matt Greathouse said about half the 75 additional Flock license plate reader cameras have been delivered. The remaining cameras should be in place in the coming weeks, Greathouse told the Lexington-Fayette Urban County Council’s Social Services and Public Safety Committee during a Tuesday meeting.

The Flock cameras launched last year under a pilot program. The cameras take photos of license plates and run those license plates against various databases. As of April 12, Lexington police have said the cameras have helped them locate 152 stolen vehicles, 18 missing persons and has led to the arrests of 245 people.

But many worried the cameras would be placed in largely minority neighborhoods and areas. Others have pushed the city to release the current and future locations of the cameras. Police had said they would release the locations after more cameras were added.

Police said they were concerned people would avoid the areas where the cameras were located when there were only 25 cameras on Lexington streets.

Some council districts with large minority populations have the most cameras, according to an analysis of police and U.S. Census data.

Cameras by council district:

Council District 1: 20

Council District 2: 6

Council District 3: 2

Council District 4: 8

Council District 5: 3

Council District 6: 15

Council District 7: 7

Council District 8: 13

Council District 9: 1

Council District 10: 4

Council District: 11: 15

Council District 12: 6

The council district with the most cameras is Council District 1, which includes much of the city’s north side. Council District 1 is 56% non-white, according to Census figures. It has the largest minority population of any council district.

Council District 6, which includes part’s of the city’s east side, has 15 cameras and is roughly 25% Black or Hispanic. Council District 11, which includes much of the Versailles Road corridor, is 37% Black or Hispanic.

In contrast, Council District 9, which includes areas around Shillito Park, is slightly less than 8% non-white and has only one camera.

However, not all council cistricts with large minority populations have lots of cameras.

Council District 2, which includes neighborhoods in the Leestown Road area, is 39.7% Black or Hispanic. Six cameras have either been installed or will be installed in that area.

Police data from 2020 to 2022 show the most violent crimes reported were in Council District 1 and Council District 11.

Still, Councilman James Brown said during Tuesday’s council committee meeting he has heard concerns from minority communities the cameras are used in areas where people feel they are already over-policed.

“Flock cameras are placed where crime happens,” said Chief Lawrence Weathers. Weathers said he understands the concern about over policing certain neighborhoods.

“Those might be areas where people are over-victimized as well. We have to take into account what the victims want as well,” he said.

Expansion into ‘real-time’ intelligence center

The city is starting a real-time intelligence center that will use the city’s more than 130 traffic cameras, Flock license plate reader cameras, and cameras owned by private residents or businesses to help police solve crimes.

The city’s traffic cameras have been available for the public to view since 2016. The location of those cameras is determined by traffic engineering.

Until recently, those traffic cameras did not record. Those cameras are now recording, said Greathouse.

Greathouse said police have given presentations to 37 different community groups.

Police are asking for $150,000 for Fusus software, which will allow the police to use both public and private cameras to help solve crimes, in Lexington Mayor Linda Gorton’s proposed $505 million budget. In addition, the police are asking for two new intelligence analysts to staff the new center.

Businesses and residents can voluntarily sign up for the system.

“It’s not mandatory,” said Greathouse.

The videos are only kept for 60 days by state law, he said. If the video is needed in an investigation, it will be kept for longer than 60 days.

“We are not constantly watching it,” Weathers said.

If an officer needs video because a crime has occurred — say a hit and run accident — the request for the video will go to the new intelligence analysts, Weathers said. The police will monitor who is requesting videos and why, he said.

ACLU, others have concerns

Greathouse said the department has spoken with the American Civil Liberties Union of Kentucky, the local chapter of the NAACP and the Lexington-Fayette Human Rights Commission about developing policies for the retention of the video and how the real-time intelligence center will be used.

Those groups have also had input on license plate reader cameras and body cameras, he said.

Councilwoman Tanya Fogle said she has spoken with those groups and some have concerns.

That’s true.

“ACLU-KY has grave concerns about the impact on residents’ privacy and other potential pitfalls of such a surveillance system,” said Kungu Njuguna, a policy analyst for the ACLU of Kentucky. “As the city is aware, we offered feedback but in no way endorse the systems as they have been designed.”

Greathouse said they are looking at some of the concerns raised by the ACLU and others as it develops policies for the real-time intelligence center. Those polices will be available after the real-time intelligence center is active. The council must approve the purchase of the Fusus software in Gorton’s budget.

That means the real-time intelligence center won’t be operational until later this summer at the earliest.

Fogle, who represents Council District 1, said she and her constituents still have concerns about the use of the cameras, but she was relieved the cameras were going throughout the city and not just in Council District 1.

“I’m still not comfortable with it,” Fogle said, but she said she also sees how the cameras can help police solve crimes.

Councilwoman Jennifer Reynolds, who represents Council District 11, said she, too, understands people’s concerns about surveillance. On the other hand, residents want crimes solved.

“I was hesitant at first,” Reynolds said. “People don’t want surveillance.”

“However, with video and still photos you can solve crimes a lot faster if you have evidence of that crime,” she said. “We get a lot of phone calls about crimes that aren’t solved or a shooting where no one was found. If used properly, it can really be a tool that can help solve crimes.”