Where the money goes: Foster families get paid, relatives caring for children get nothing

Editor's note: This is the sixth part in a six-installment series about Native American children in South Dakota's foster care system, produced in partnership between the Argus Leader and South Dakota Searchlight.

Eighteen-month-old Gabriel slowly fell asleep in his grandmother’s arms at the dinner table.

It was mid-morning, and his two siblings were playing quietly with their uncle downstairs. Gabriel didn’t need his crib, or a security blanket or sound machine lulling him to sleep. He just needed his grandmother’s arms — a safe space. His home.

Gabriel is one of 13 grandchildren living in Jewel Bruner’s three-bedroom, brown clapboard home in Eagle Butte on the Cheyenne River Reservation. Eight of those children live permanently with Bruner since she has tribally recognized custody of them. Her daughter, who struggles with a meth addiction, asked her mother to care for the children.

“I’ve been more of a mother to them than a grandmother,” the 55-year-old said.

Bruner’s house is crowded and she struggles to find enough food or supplies for the children at times. But it is a house filled with love.

She will do everything in her power to keep her grandchildren out of foster care, and to keep her family from breaking apart like it was broken decades before when she and her siblings were separated by the foster system.

Aside from Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program payments and emergency food assistance through her tribe, Bruner doesn't receive governmental support payments. Nor does she receive counseling or non-financial support from the state or tribe to relieve the burden of eight children permanently in her care.

Bruner's grandchildren were some of the 345 Native American children in fiscal year 2023 in kinship placements (with a family member who cares for the child instead of being placed into foster programs), according to the state Department of Social Services.

A quarter of all foster children in 2021 were placed in kinship care, with Native American children accounting for 53% of the kinship placements, according to the National Data Archive on Child Abuse and Neglect.

Bruner and other kinship families say the lack of support is a massive barrier preventing others from accepting a kinship placement. Foster families also say they don't have the state support needed to properly care for children in the system, leading to burnout and poor retention rates among foster homes.

An Argus Leader/South Dakota Searchlight investigation examined the issues Native families and children face inside South Dakota’s child welfare system. Native American children accounted for nearly 74% of the foster care system at the end of fiscal year 2023 — despite accounting for only 13% of the state’s overall child population.

Many of those children are placed in non-Native foster homes with family and cultural dynamics different than theirs and potentially hundreds of miles away from their home, since 11% of licensed foster families in South Dakota are Native American.

Kinship placements are the priority placement for all children who are removed from their families, said state DSS Secretary Matt Althoff. Under the federal Indian Child Welfare Act, Native American children, when removed by child welfare services, are to be placed first with relatives and if that is not possible, they should be placed into Native American foster homes.

But oftentimes, Althoff said, family members of Native American children aren’t eligible because their house doesn’t fit specific criteria or they may fail the background check. Sometimes relatives can’t be found. Those children are then placed in foster homes across the state.

Gov. Kristi Noem’s administration has made headway to recruit more foster families across the state through the Stronger Families program, launched in 2021. The Stronger Families website identifies Native American foster families as one of the greatest needs for foster parent recruitment. The need is also advertised at events and on social media.

"There's got to be a point where we start communication of what's best for these children," Noem said. "Our desire is to have these children with family close to home, in a home that mirrors their culture and upbringing as well. We just need it to be a safe environment."

But the state can do much more to incentivize Native American kinship and foster family enlistment and retention, families say.

Kinship families do not receive any financial support for placements

Historically, kinship care is a cultural norm and a traditional family system in Native American communities with grandparents, aunties, uncles and other extended family members serving as caregivers for brief or extended periods of time when biological parents can’t provide care.

Studies have found that kinship care provides benefits to children, such as fewer behavioral problems, fewer mental health disorders, and less placement disruption than in the traditional foster care system. Those children are also more likely to be employed or enrolled in formal education at age 21 and less likely to require public assistance, be homeless or be incarcerated compared to youth placed in non-kin foster care.

Natasha Eagle Star and her wife maintain one of the 98 licensed Native American foster homes in the state. Based in Winner, the two became state-licensed foster parents because they wanted children and knew Natasha had family members in the system.

“When we saw that, we knew there was a need right away,” she said.

The couple have adopted four of the children and have guardianship over two other children they’ve cared for in the last seven years — three of the four adopted children had family ties to them. They now only accept emergency foster placements.

Eagle Star explained that having a familial connection to her children is culturally important. Before the adoption process started, she spoke with the children’s direct family to ensure adoption was best for them.

"That's important for the kids to understand who they are, where they came from," she said. "We make sure that those families are involved. They either talk to the children still or they get updates from my wife.”

Kinship families in South Dakota do not get a Title IV-E payment like foster families do. The federal program is meant to financially support foster care and out-of-home placement for children. Nor does the state offer financial support for kinship families, Althoff confirmed.

“The problem with those placements is they’re not fully eligible, meaning the family can’t get foster care money,” said BJ Jones, director of the Tribal Judicial Institute at the University of North Dakota. “And ICWA actually says that when a tribe licenses a home, the state has to honor that.”

Comparatively, a foster family is paid between $670 and $1,300 a month to cover a child’s expenses — clothing, food, medical needs or even a new bed for them to sleep in when they first move in — depending on their age. Kinship families get nothing.

The Eagle Stars are state licensed foster parents, but they never received financial support for the children they took on as kinship placements — even though the children were already in the foster care system, and their previous placements received a monthly stipend. They did however, receive foster stipends for non-relative foster placements that stayed with them.

If the kinship member watches the child for a set period of time and becomes the child’s guardian, kinship families are eligible for federal Kinship Guardian Assistance Program funding. On average, 29 South Dakota children received Kin-GAP funds each month in 2021, collecting $80,385 for the year.

In Bruner’s household, she participates in SNAP, which has helped her buy food, and she also receives social security benefits. She has no other income since she’s retired while her co-parent has a part-time job.

More: ‘Waiting for life to start again’: Family agonizes over parental termination

Some other states, including Wisconsin and Arizona, offer financial assistance for kinship families without requiring them to become licensed foster families. But it’s still less than what foster families receive.

The state could implement its own kinship payment rates to support families, Gov. Noem told South Dakota Searchlight and the Argus Leader, but that would be a discussion for state lawmakers to have during the legislative session, which starts in January.

Foster parent burnout and turnover lead to farther displacement for children

Holly Christensen, executive director of the Foster Network in Sioux Falls, has found state support for foster families in South Dakota lacking — whether that be financial support, accessing supplies or getting foster and kinship families connected to counseling services. She’s not the only one — both Eagle Star and Bruner echoed the sentiment.

Support for foster families looks different based on where they are in the state. The same things that are speedily reimbursed by the local DSS office in Sioux Falls may not be reimbursed by the Rapid City office, Christensen said. It depends on who is working in the office, the amount of staff turnover and what the process is like there.

“As a foster parent, I know a lot of others who won’t take kids from Rapid City anymore,” Christensen said.

Christensen was never reimbursed for $500 in medical expenses her adopted twin sons needed while she was fostering them during the COVID pandemic. The twins were originally from the Rapid City area and are Native American, though Christensen, who is non-Native, was never able to confirm if they’re enrolled members of the Rosebud or Oglala Sioux Tribes.

That lack of support creates an imbalance of foster families across South Dakota, she said.

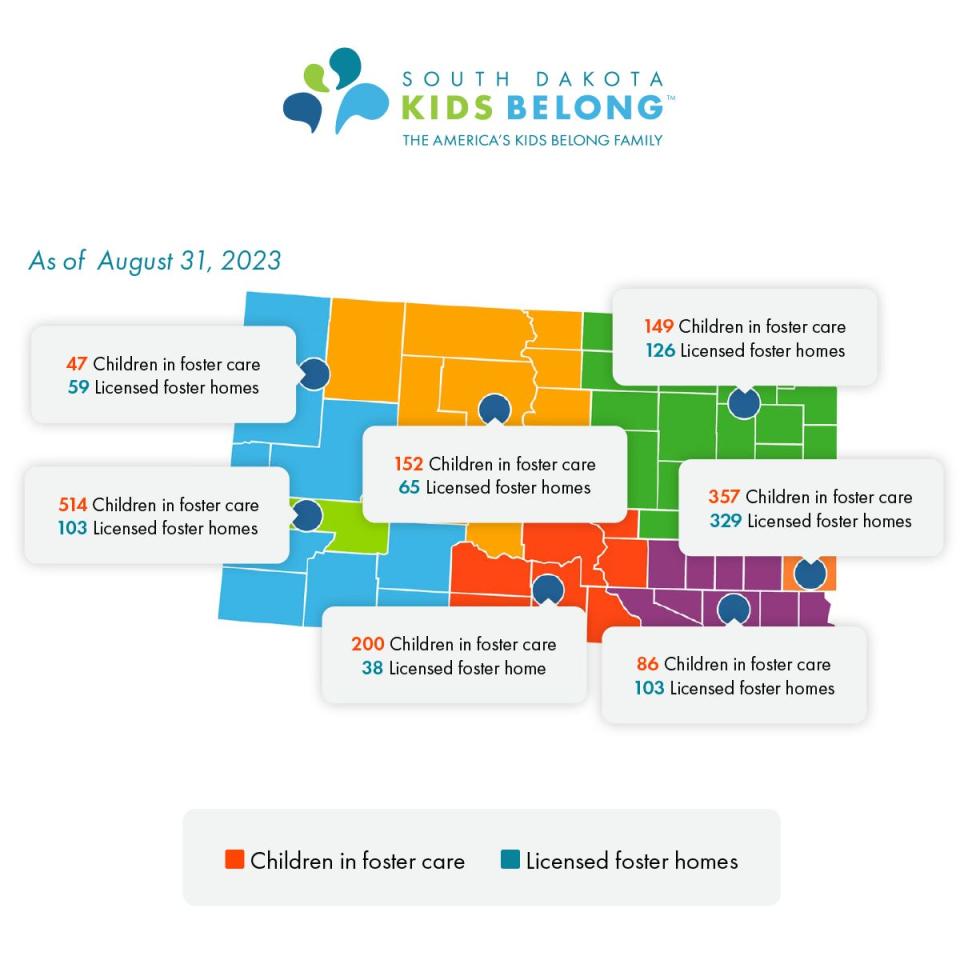

Over one-third of all foster kids in the state, 514 children, come from Pennington County. Yet only 103 foster families are licensed in the county, according to August 2023 statistics from South Dakota Kids Belong. Two other regions in the state, which include Standing Rock, Cheyenne River, Rosebud, Lower Brule and Crow Creek reservations, have more foster children than they do licensed foster families — even if each household took in two foster children each.

As of Sept. 30, 2023 there were 41 state licensed foster families living in a county that includes reservation boundaries, according to the state DSS. There are 245 state licensed families living in counties immediately adjacent to reservation land.

That means a significant number of children are shipped hundreds of miles across the state — even so far as from Rapid City to Sioux Falls.

The southeast region of the state, which includes Sioux Falls, accounts for 53% of the state's foster homes.

“Why are we sending so many kids to Sioux Falls instead of advocating in Rapid City? Because there is a need,” Christensen said. “It’s obvious the kids are not being placed in or near their own communities.”

That same lack of support is why Christensen says South Dakota has low foster parent retention rates.

The retention rate for foster families in South Dakota for the last three years hovered around 72% to 75%, according to the state DSS.

It’s more difficult for kinship families, Christensen added, because they are emotionally connected to the child’s parents and don’t have the same resources.

“There’s no support from the system,” she said, adding that it can be difficult for kinship families to find resources or nonprofits without the same help foster parents get from the state.

The state recently created a kinship navigator role and is hiring for the position, which will help kinship families find resource options.

Difficulties recruiting foster families: Mistrust in the system

Christian Blackbird is the ICWA director for the Crow Creek Sioux Tribe in central South Dakota. He works with the state to coordinate placements for children who are tribal citizens and ensure ICWA guidelines are followed.

He’s seen a disconnect between efforts at the tribal and state level to find kinship placements.

“I’ve been to a couple of court hearings where the caseworkers would tell us that they exhausted all their efforts finding relatives,” he said. “Then I come to find out that some of the relatives weren’t even being notified, like distant relatives or aunts or uncles, so we ended up having to intervene and send out letters saying we did find relatives of the children.”

Grandparents are often left out of the foster care system and from decisions regarding child placements, said Madonna Thunder Hawk, a Lakota activist and member of the Cheyenne River grandmothers group. Grandparents aren’t usually selected as kinship placements – oftentimes without an explanation from authorities, she said – and state social workers prefer to interact with the child’s parents. For example, foster parents may not normally contact family beyond parents.

Jones, who served as a South Dakota lawyer and tribal judge before working at UND’s Tribal Judicial Institute, said he was usually able to find a family member to care for the child.

More: South Dakota inspired ICWA but still has high rate of Native children in foster care

“But that didn’t necessarily mean the state would license a family member,” he added.

In South Dakota, foster families must be licensed through the state unless they are located on a reservation. Families living on a reservation can become tribally licensed foster families. But for enrolled tribal members who want to be foster parents and who live off reservation land, they must register with the state to receive placements.

A 2004 state ICWA commission determined allowing tribes to license homes on and off reservations would lower the number of children in foster care.

Both tribes and the state are working in the best interest of the children, said Jessica Morson, the South Dakota ICWA Coalition director and ICWA director for the Flandreau Santee Sioux Tribe.

"We do the same work, we have the same education, but yet you're still going to question where I'm coming from in regards to keeping this child safe, saying this is a safe family," she said. "The same background checks are run."

The federal Native American Children's Safety Act, which was passed in 2016, imposes "more onerous" requirements on tribes when licensing foster homes in the state, Jones said — meaning the standards should be just as good, if not better, than the state.

Native kinship and foster family recruitment remains one of the “bigger problems” in South Dakota, Jones said.

“They can't find enough homes to place these kids in,” he said.

Some Indigenous families are hesitant to let the state tour their houses, Eagle Star said, afraid the state will see how they live and take their own children — warranted or not. Many households on the Rosebud Reservation have between eight and 13 family members living together, Eagle Star said.

“I can understand from the tribal side why someone wouldn’t want to be a state foster parent,” said Eagle Star, the state-licensed foster parent. “No one wants DSS in your house every month. And it’s a lot of work to have non-Natives come into your home to judge and inspect it. A non-Native person may not understand the Native way of thinking or life. To have them come into your home, your sacred space where you raise your children and feel most comfortable, is hard.”

What is being done about it

Eagle Star and Christensen are working in their networks to recruit and support foster families across South Dakota. The South Dakota ICWA Coalition and members of the state DSS participated in a joint foster parent recruitment training in Rapid City in September.

The state is also taking an active effort through Noem’s Stronger Families program. The program was successful in its first year, according to a press release at the time.

According to a records request filed with the state Department of Social Services, the number of newly recruited foster families doubled in the initiative's first full year of implementation (246 in fiscal year 2022) but dropped to 183 families the following year. While that's a 12% increase from 2021, it does not meet DSS' defined goal to recruit 300 new foster families each fiscal year.

"It's been challenging at times to continue to keep that type of momentum, but the awareness factor, I think, is important," Noem said.

The growth in Native American foster families, however, increased from 90 in fiscal year 2020 to 98 in fiscal year 2022 — though Noem did say that the increase in Native foster homes during her tenure has been more pronounced than years prior. There were 58 state-licensed Native American foster homes in South Dakota in 2012.

“Our focus has dramatically improved the situation,” Noem said.

But a state constantly recruiting foster families may be a sign there’s a problem within the child welfare system, said David Simmons, the director of government affairs and advocacy for the National Indian Child Welfare Association.

“We know there are families and relatives who want to help, but if you’re not using those resources and tools you’re just going to be stuck,” Simmons said. “There’s no amount of money, there’s no amount of additional commitment to removing children that’s ever going to change or fix the child welfare system.”

‘When you go through that you become more protective’

Looking down at Gabriel, whose slow puffs of breath caress Bruner’s cheek, the grandmother was transported back 40 years, to a memory of holding her younger brother in the same way.

They were in a caseworker’s office, where she and her eight siblings were separated into foster homes across the state.

Bruner was in and out of foster care in the 1970s and ’80s due to her mother’s alcoholism. When her mother’s parental rights were terminated, Bruner was shipped to Oregon to live with her uncle while her other siblings were split between South Dakota and Illinois. And while Bruner and some of her siblings returned to Eagle Butte, the physical distance from their childhood fractured their emotional connections.

"When you go through that," she said, her voice thick with tears, “you become more protective. I can say it does eat at you, because even though it was years ago, it still chokes me up today when I think about my brothers hanging on to me, crying and not wanting to go with the caseworker."

And while Bruner doesn’t want her eight grandchildren to go through what she did, she’s struggling without the support she needs.

She knows the children are cared for and loved, and that she’ll support them through whatever may come their way.

But her daughter is pregnant with her ninth child, still struggling with a meth addiction and going in and out of jail. With so many lives depending on her already, Bruner is unsure if she’ll take the newborn. But if it comes down to it, Bruner said she'll do it to keep from losing the baby to the foster care system.

EDITOR'S NOTE: This story has been updated since its original publication with new statistics on foster family recruitment provided by state government.

This article originally appeared on Sioux Falls Argus Leader: Difference in kinship and foster family support leaves caregivers wanting more