While Kentucky debates licensing for smoking retailers, Louisville already is doing it

Kentucky lawmakers might be asked this winter to consider a bill that would require tobacco and vape retailers to register with the state and, as a condition of their license, risk being shut down if they’re caught selling to minors.

This isn’t a new idea. Most states other than Kentucky have such a licensing law for smoking products retailers.

So does Louisville, Kentucky’s largest city, even if it isn’t being fully enforced yet.

As of Jan. 1, 2022, retailers who sell tobacco products, tobacco paraphernalia (such as pipes or rolling papers) or vape devices in Louisville must buy a license from the Louisville Metro Department of Health and Wellness.

Initial applications, including a zoning check on their street address, cost $35. Annual renewals cost $10.

About 850 retailers were registered by late November, city health officials said. The licenses let officials know exactly where smoking retailers are supposed to be operating, something that can be more of a mystery for state regulators elsewhere across Kentucky.

The licensing law and a related zoning law also give the city tools to prevent new stand-alone smoking retail stores from opening within 600 feet of another such store or 1,000 feet of facilities that serve children, such as schools, parks, public playgrounds, daycare centers, outdoor recreation areas, athletic facilities or community centers.

The Louisville Metro Council passed the laws in November 2020. The council was responding to residents’ complaints about smoking retail stores clustering together, especially in low-income neighborhoods, and attracting youths.

Under state and federal law, smoking products can’t be sold to anyone under the age of 21.

Tony Florence, whose 723 Vapor chain of vape product shops has locations in Louisville, Lexington and Nicholasville, said the licensing law hasn’t created any problems for him.

“Louisville has got it figured out,” Florence said. “You can get your license online, it’s super-simple, the cost isn’t prohibitive.”

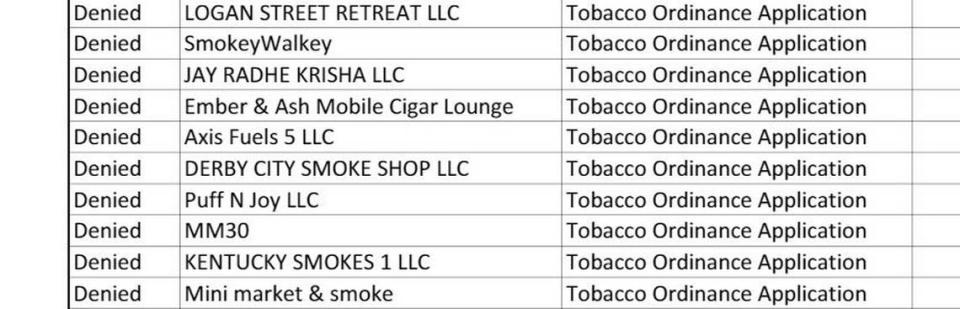

Over the last two years, Louisville has rejected 64 license applications, usually because a retailer wanted to open a store too close to a school or in another prohibited location, according to the health department.

However, no enforcement actions have been taken so far against the licenses of stores cited by the Kentucky Department of Alcoholic Beverage Control for selling smoking products to minors, in violation of state and federal law.

The city ordinance clearly states that retail licenses can be suspended or revoked for any violations of law related to the sale of smoking products.

According to a Herald-Leader analysis of ABC citations, during the 21 months from November 2021 to August 2023, the ABC cited Louisville retailers about 200 times for selling tobacco or vape products to undercover minors who worked for the agency.

In 37 instances, Louisville retailers were cited two or more times during this period.

Health officials said in a recent interview that they’ve just begun working on the enforcement part of the law.

Louisville’s health department was assigned its new duties on tobacco retail licensing around the same time the COVID-19 pandemic hit three years ago, with COVID understandably dominating the agenda for many months, said Nick Hart, director of the city’s Division of Environmental Health.

Funding provided by the relatively small licensing fee has not provided enough money for the city to hire more staff at the health department, Hart added.

By contrast, Cincinnati charges $500 for its annual tobacco retail license fee, allowing it to dedicate full-time employees to enforcing the law on licensing and compliance checks on sales to minors, he said.

“It took us a great deal of funding and capacity to pull people away from COVID response to actually design and build our electronic management system that we use,” Hart said.

“We’re still in the very early stages of going out and doing that active compliance enforcement and revocation.”

At present, the health department is checking on the 64 denied applicants to make sure they did not simply open at the rejected locations without a license, said Patrick Rich, the city’s environmental health administrator.

“I think we’ve been able to get to 12 in the past four or five days,” Rich said. “One of those was actually operating without a license, so now we’re taking action there.”

“The other 11 have all either changed their business models and have opened up something else or else they just didn’t open a business there. So it does appear to at least somewhat be anecdotally be working the way we intended it to work.”