In Whippoorwill, Okla., drinking water from Hulah Lake is no more

Nestled 20 miles northwest of Bartlesville in the quiet rolling hills of Osage County's cattle and oilfields, the seemingly forgotten rural communities of Whippoorwill, Oak Ridge and Bowring have been fighting a decades-long battle to control their own water supply.

Through years of pipeline breaks, boil orders and water quality problems, residents worked together as a community to create a water system they could be proud of.

Now the 50-year-old water treatment plant is becoming another casualty in a war of identity and autonomy for a community that has watched as gas stations and grocery stores slowly disappear and their dependency on larger cities, like Bartlesville, grows.

Within a month, they will be forced to switch from pumping water from nearby Hulah Lake and the Caney River to paying to have it piped in more than 10 miles from Copan.

Once the treatment plant goes dark, those who fought to keep the water district afloat will no longer have the shared passion that has bound them together for years.

"It's tough. One side feels like they are losing the little control they have, but they had time to get where we need to be. And we keep coming up short, and we need water," said state Rep. Judd Strom, R-Copan, who gets his water from Osage County Rural Water District #20.

Where everyone knows your name

In Whippoorwill, the buildings show their age as a testament to days when residents would line up for the all-you-can-eat $5 fish fry and live music at Jim's Place.

Owner Jim Edens has spent the last six years working out of an office tucked inside his restaurant − which he claims serves better hot hamburgers than Murphy's in Bartlesville − operating and maintaining the water treatment plant.

He says he took over operations of the plant in 2016 when the district was under a boil order. He and his grandson worked for a year without being paid just to make sure the community had water.

"I just was helping the plant, and one day I looked around, and I was the only one left," said Edens, who is also a volunteer firefighter in the area. "I liked having water. No one else was willing to step up and help."

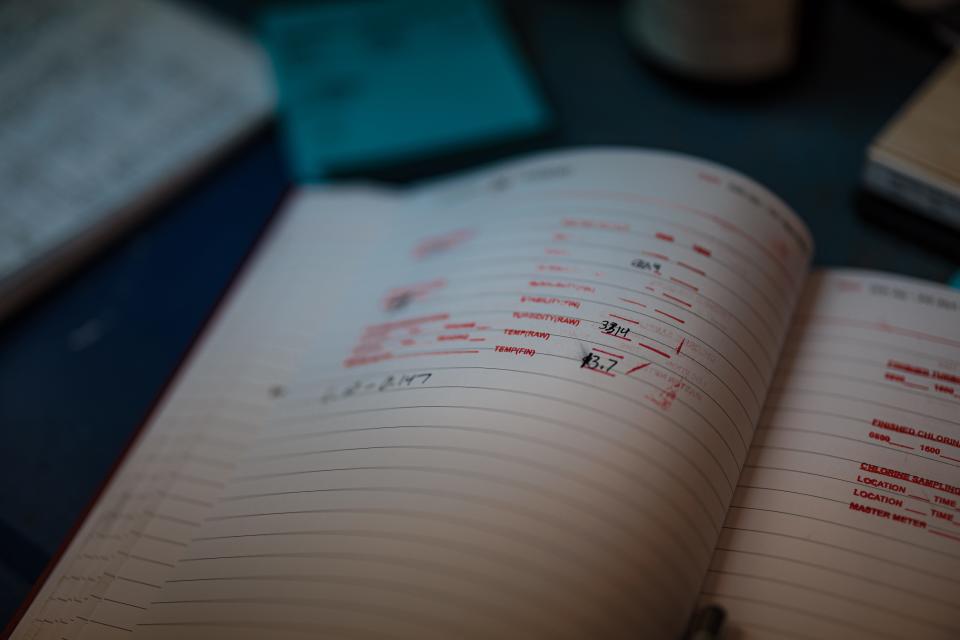

Working with the local Oklahoma Department of Environmental Quality office in Bartlesville, Edens has done everything from retrofitting parts to balancing chemicals through the years. He even spent last Christmas Eve repairing a broken water line in freezing cold weather so his neighbors would have water for Christmas.

Differing ideas

The Hulah Lake community is divided over the switch to Copan water. Some welcome the change, while others feel abandoned and unappreciated for their sacrifices to keep the plant running and water flowing to their neighbors.

But the water district has struggled to meet the ever-increasing demand for federal water quality over the years, said Shellie Chard, water quality division director for the DEQ.

"They historically have had a lot of issues," she said. "They've had multiple drinking water emergencies, and we've had to request the National Guard come in and help supply water for an extended period of time."

Chard says DEQ has worked with the water district for the last few years to come up with a solution to solve ongoing issues, but realized that moving the community's water source to Copan was the best solution.

Pat Barnett, who has served on the District #20 board since its inception in 1968, begs to differ. She says DEQ is sacrificing her community's water treatment plant to pay for upgrades at Copan. And she believes the agency should share in the blame for the lack of water quality.

"In the beginning, we needed the water badly, and everybody went together and worked for it," said Barnett. "Those days are gone."

A troubled past

The water district's troubles began in the 1990s when DEQ forced a switch to a water filter system that was designed for spring water, not the river water they were drinking, Barnett said.

"I begged, I pleaded with Patty Thompson [of DEQ] 'til I was blue in the face that we knew nothing about this system," said Barnett. "We were forced to use it and it did not work."

Over the next decade, the system slowly drained the water district's resources by constantly having to purchase costly new filters after the muddy river easily clogged them. The district also lost several plant operators because of frustrations with the system, she said.

By 2016, the water district board had had enough. It allowed the self-taught Edens to take over as plant operator and to design and build a new sand filter system. Within three months of completion, the plant was producing pristine water, Edens said.

"It was working," said Barnett. "We called DEQ and when they walked into the plant, they could find nothing wrong."

Barnett said Edens couldn't have done it alone, and the community rallied with some help from the local DEQ office.

"Mark Hershey from the DEQ office in Bartlesville was fabulous help," said Barnett. "Jim could call him, he would come up, help him with the testing, show him what to do."

A decision made

In recent years, Barnett and Edens said they had hoped that DEQ would allow them to keep the water treatment plant that they had spent the last six years fine-tuning or would help locate funding for upgrades, especially since it had met new quality standards.

But Barnett said she believes the agency had already made the decision to award Copan a multi-million-dollar water treatment project to upgrade its plant and to take District #20 in as a customer.

"I begged, I'm serious, I begged," said Barnett. "I said 'Give me half of that money and we will have you a processing plant up here that you'll bring tours to show you how to deal with our kind of water.' "

But Chard points to the district's nearly 200 water quality violations over the last 20 years, compared to Copan's 33 violations during the same time period, according to the Drinking Water Watch website.

"They also have construction and operational violations," she said. "[They] really lack some of the technical, managerial and financial capacity to manage and operate their system continuously and comply with ever-expanding federal drinking water standards."

In the end, DEQ made the best decision it could, by requiring District #20 to get its drinking water from Copan, she said.

"They feel that it takes away some of their autonomy or even some of their identity, but honestly, what we're concerned about is providing safe drinking water to all Oklahomans," said Chard.

Supply uncertainty

According to Barnett and Edens, Copan's water department recently informed District #20 that they weren't sure they could meet the community's water demands as engineering for the project was done years ago and Copan's needs had increased at a higher rate than initially estimated.

The Copan water department couldn't be reached for comment about its capabilities. And DEQ said they hadn't heard about any issues with Copan's inability to meet demand.

In an almost defiant final act, District #20 plans to only disconnect − not decommission − the water treatment plant, in case there are issues with Copan's water supply.

"They said we had to take it all apart, but we are just removing a small section of pipe," said Edens. "Give me 40 minutes − I will have it up and running again."

This article originally appeared on Bartlesville Examiner-Enterprise: In Whippoorwill, Okla., drinking water from Hulah Lake is no more