White America has an ingrained fear of blackness. It’s time to let go of that fear

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

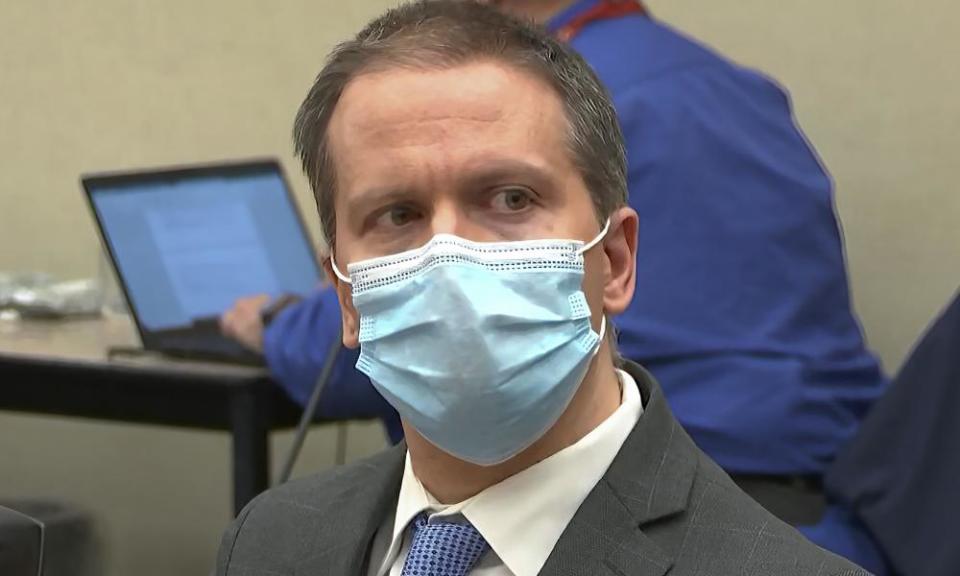

It has been a year since George Floyd last drew breath. It has been a year since the multiple videos of his death spread worldwide; since passionate demonstrations swept cities and towns; since personnel carriers filled with soldiers crawled through American streets; since “saying” his or her name became a ubiquitous incantation, an infinitely unspooling litany of death. In the year since, Derek Chauvin, the police officer whose coldly dispassionate gaze riveted our own, was convicted on all counts. It was hard to unsee. And we saw.

Moreover, the witnesses against him included the chief of police; the instructor in techniques of restraint at the academy where Chauvin had trained; the police dispatcher who was watching remotely and thought her screen was frozen because he stayed on top of Floyd for so long; the emergency medical technician who had to reach around Chauvin’s knee to take a pulse (there was none) because Chauvin refused to move even after the ambulance had arrived; Floyd’s weeping (white) girlfriend who testified to his gentle, generous and prayerful nature; the sheer number of bystanders who “called the police on the police”; the crying children; the shopkeepers; the passing martial arts professional who shouted at Chauvin repeatedly, telling him that that he was killing Floyd. I began my own career as a prosecutor and I have never seen a stronger case.

There simply was no question.

And yet … there was. Indeed, there was such great collective apprehension about whether Chauvin actually would be convicted that thousands of troops were called to the streets of Minneapolis before the verdict was read. That apprehension was a testament to how rare it is that police are convicted of even egregious misbehavior. Indeed, if Chauvin hadn’t been convicted, the biggest issue would not have been the much-discussed potential for riots, the larger emergency would have been whether there exists any legally enforceable limit at all to police’s exercise of deadly force.

A year on, any optimism I harbor is built on our aversion of that existential crisis. And yet I continue to worry because there are other cases. I worry because there is such a strong acculturated sense about who is presumed innocent or not in racial encounters, about who may be categorized as inherently “angry” or “threatening”. (Part of Chauvin’s unsuccessful defense rested on trying to depict the protesting onlookers as distractingly “angry”, “threatening” and unruly.)

At this vexed moment, it is a truism that Americans of different races, ethnicities and religions are tense, wary of one another; but it is white fear of blackness that has the longest history, that is most intractable, and that still underwrites majoritarian tendencies to forgive even lethal police misconduct, and to rationalize punitive forms of segregation in housing, education and employment.

In the domain of criminal procedure, that generalized fear is an evidentiary problem. Not just police officers, but self-appointed citizen vigilantes are often not prosecuted or charged at all when they allege mere free-floating decontextualized fear. If such cases actually proceed to trial – again, the Chauvin trial was a rarity – the deployment of wildly unreasonable subjective fear is often sufficient to justify killing innocent, unarmed people. I feared for my life. Who are you to judge?

These are the two forces that we must bring into contention as a widespread pattern of response. “I feared …” as a subjective standard of self-exoneration. And then the follow-up banishment of any juridical review of that fear: “Who are you to judge?”

This pair of immunizing assertions is built into the very structure of recent so-called “stand your ground laws” that expand self-defense as licensing shooting to kill, unqualified by any duty to retreat, in public places even where there are other non-violent options. Although such laws are race-neutral in language, dominant American assumptions about who can claim a sidewalk or public street as ground that is “yours” is a highly raced proposition.

Consider Mark McCloskey, a personal injury lawyer from Missouri who, days ago, announced his intention to run for US Senate in 2022. McCloskey achieved memed infamy last July when journalists captured pictures of him and his wife, Patricia, brandishing guns and aiming them at a group of mostly black protesters who were passing their house en route to the mayor’s residence located farther down the street. McCloskey’s campaign website describes the couple as having “held off a violent mob through the exercise of their 2nd Amendment rights”.

But there was no violence: the McCloskeys were upset because the crowd had transgressed a wrought-iron gate at the top of the street which the couple felt marked a boundary line between the entire neighborhood complex as a “private” venue and the public thoroughfare beyond. (There are at least 285 gated streets in St Louis, part of what urban planner Oscar Newman called the “defensible space theory”, designed to create as sense of privacy even when residents benefit from publicly subsidized police, sewer, fire and water services.)

Once the protesters passed through that gate, McCloskey claimed that they “may as well have been in my living room … I was frightened. I was assaulted.” He felt that it was “like the storming of the Bastille”. “They’re angry, they’re screaming. They’ve got spittle coming out of their mouths. They’re coming towards our house.” The couple’s decision to display and point guns – an AR-15 assault rifle no less – was dressed in the legal terminology of immediacy, McCloskey insisting he was in “imminent fear” that “they would run me over, kill me”, and that “we’d be murdered within seconds. Our house would be burned down, our pets would be killed.”

Again, the protesters were not in Mark McCloskey’s living room. They never so much as set foot on his lawn. They walked past his house. They did not “storm” his home. They passed, chanting loudly but entirely peacefully.

In some neighborhoods any black person may be looked upon with suspicion. As a friend describes it, “it’s an almost magical power: we can inspire fear just by appearing.” I wish I could shrug off the McCloskeys’ exaggerated fear as idiosyncratic or delusional, but it’s not isolated. Fox News pundits such as Tucker Carlson or Sean Hannity give round-the-clock voice to the many white people who share the McCloskeys’ effusive and globalized fear of black people on “their” streets. That fear has inspired proliferation of dozens of “anti-riot” bills initiated in state legislatures, apparently aimed at Black Lives Matter protests (but not at the largely white crowds who broke into public buildings across the country culminating in the assault on the US Capitol on 6 January.)

Consider just one bill, introduced in Alabama’s legislature in February 2021: had it been enacted, it would have “provide[d] that if an active riot is occurring within 500 feet of the premises, a person in lawful possession or control of the premises may use deadly physical force to defend the premises from criminal mischief or burglary”. Happily enough, the bill was defeated. But it illustrates a too-ubiquitous sentiment percolating through our polity. Authorizing not just the police but private citizens like the McCloskeys to use lethal force – based on subjective perceptions of danger to things, not just to persons – is a rationalized mitigation of culpability almost never extended in practice to black people.

Mark McCloskey, meanwhile, has sworn fealty to “Donald Trump’s agenda” in announcing his new “call to public duty”. As his website summarizes it: “God came knocking on my door last summer disguised as an angry mob.”

In the year since George Floyd died, I am relieved that the jury found Derek Chauvin guilty of murder. But anti-protest laws and anti-Black Lives Matter backlash have been significant responses to the attempted reform movement that his death inspired. I cannot yet dismiss the thrumming of those who insist that it is “natural”, obvious, rational and “reasonable” to apportion our collective fears by “colorblind” but coded hierarchies of racial “threat”. Fear should not govern everything. Fear cannot excuse everything. Fear heals nothing. And healing is the hard road still ahead.