White House history can't be rewritten: How early presidents failed enslaved people

Many of America’s early political leaders benefitted directly and indirectly from slavery. Eleven of our first twelve presidents were slaveowners or relied on enslaved labor at some point during their presidency. Although free Black and White people also worked at the White House, enslaved people were key to its everyday functioning as a center of national power.

Juneteenth, which commemorates the emancipation of enslaved people in the United States, is the right moment to examine this troubling history and its impact on Black lives in the White House. That’s why the White House Historical Association’s “Slavery in the President’s Neighborhood” initiative works to tell their stories. Sharing this research here can shine a light on the enslaved individuals who built, lived, and worked in the White House.

How many U.S. presidents owned enslaved people?

At least thirteen presidents were slave owners at some point during their lives, and they often brought their enslaved workers to the White House in order to save money and use staff who knew their preferences. The president’s $25,000 salary was expected to cover all White House expenses, including food, wine, entertainment, furnishings, family expenses, and salaries for servants.

During George Washington’s presidency, at least ten enslaved people worked at the president’s houses in New York City and Philadelphia: Austin, Giles, Hercules, Joe, Moll, Ona, Paris, Richmond, Christopher Sheels, and William Lee.

Often working in proximity to paid White servants, these men and women cooked elaborate dinners, cleaned the residences, did laundry, and mended clothes. They helped the Washingtons dress in the morning, did their hair, and waited on them as they ate. They tended horses, greeted guests, cared for the Washingtons’ grandchildren, and escorted the president and his family when they went out.

White House history is Black history: We must remember that White House history is Black history. This is some of that story.

Like enslaved staff in many White Houses, these women and men were often separated for years at a time from children, parents, spouses and other family who worked at the president’s plantation homes. While living in Philadelphia, President Washington sometimes moved around his enslaved workers to evade Pennsylvania’s emancipation laws.

After the wife of Washington’s enslaved cook Hercules died, he was allowed to call for his eleven-year-old son Richmond – but had to leave behind his daughters, eight-year-old Evey and five-year-old Delia. (Richmond swept chimneys and assisted in the kitchen.)

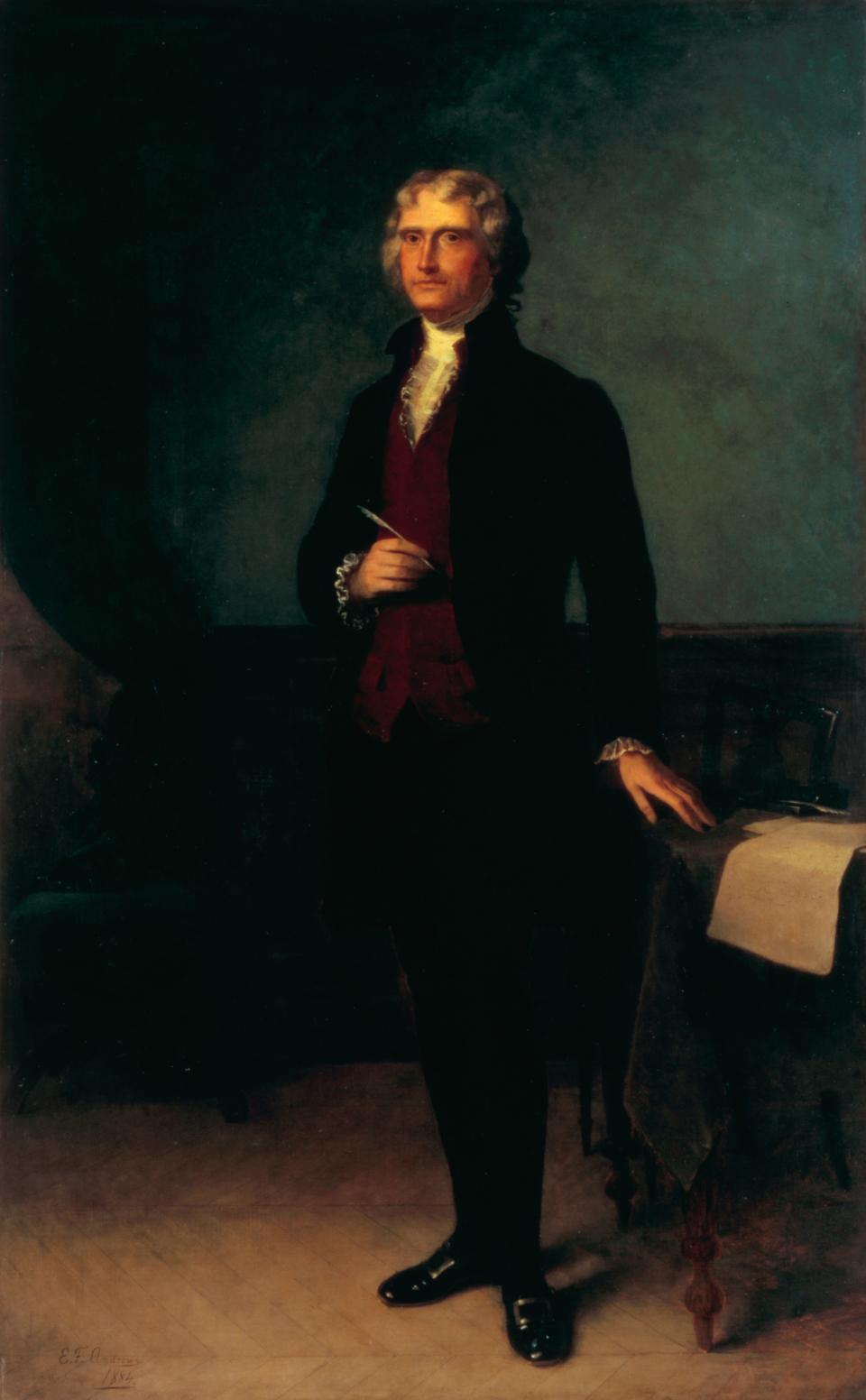

Thomas Jefferson owned over 600 enslaved people during his lifetime, the most of any U.S. president, and he was the first president to bring enslaved people to the White House (which was built largely with the help of enslaved Black workers). One of the first arrivals from Monticello was fourteen-year-old Ursula Granger Hughes, a chef’s apprentice who gave birth to Asnet, the first baby ever born in the White House. (He died not long after.)

Joseph Bolden, who cared for horses and carriages at the Madison White House, saved up enough to buy his freedom. But his wife Milley belonged to Francis Scott Key (who later composed the lyrics to The Star-Spangled Banner). When Key wrote Dolley Madison that, “Your Servant Joe has been anxious to purchase the freedom of his wife,” she advanced $200 to buy the freedom of Milley and her child – as long as they would stay on at the White House as servants, working off their debt.

One of the Madisons’ enslaved workers, the valet and dining room servant Paul Jennings, went on to write the first published memoir about life in the White House. “The east room was not finished, and Pennsylvania Avenue was not paved, but was always in an awful condition from either mud or dust,” he wrote about moving in. As the British prepared to burn the White House during the War of 1812, Jennings and other White House staff members helped save Gilbert Stuart’s iconic painting of George Washington. (Nearly two centuries later, dozens of Jennings’ descendants came to the White House to pose for their own family photograph next to the painting.)

US is divided on racial justice. Here's how we can work together.

Because records are scarce, we know too little about these men and women, who likely lived in the White House basement near their workspaces. Some have names we don’t know. Others – like Betsey, Daniel, Eve, Hartford, Peter, Sucky, and Tom, enslaved workers for President Monroe – can at least be named, thanks to expense records for shoes, clothing and medical care.

Evils of slavery entwined in White House history

Andrew Jackson brought some of his 95 enslaved workers with him to the White House, where some may have worked on the construction of the North Portico, a new stable, and the addition of running water. Jackson’s enslaved servant George slept on a pallet next to Jackson’s bed, to be available any time. As president, Jackson purchased Gracy Bradley (a skilled seamstress bought as a gift for the president’s daughter in law), her sister Louisa (a nurse for Jackson’s grandchildren), as well as eight-year-old Emilie.

Opinion alerts: Get columns from your favorite columnists + expert analysis on top issues, delivered straight to your device through the USA TODAY app. Don't have the app? Download it for free from your app store.

As the national debate over slavery grew more bitter, James Polk – who added nineteen more enslaved people to his Mississippi plantations while president, including at least thirteen children – hid the purchases by using his wife’s brother and other agents as intermediaries. Polk even briefly paid former First Lady Dolley Madison for the services of Paul Jennings (who had helped save the George Washington painting, and was still owned by Mrs. Madison).

By the time Abraham Lincoln was elected president, all White House servants were free men and women, though many had been enslaved or descended from enslaved families. One Black staffer later said that the president treated them “like people,” and Lincoln’s sons played freely with local Black children.

A White House cook named Mary Dines (who had escaped from slavery in Maryland hidden in a hay wagon) helped nurse the Lincoln boys during the typhoid fever that killed young Willie Lincoln. “Aunt Mary” also wrote letters for fugitive slaves and led them in spirituals, which brought tears to Lincoln’s eyes when he visited their camp.

Elizabeth Keckly, Mrs. Lincoln’s dressmaker, was born into slavery in Virginia. Six months after her own son George was killed in battle after enlisting in the Union forces, she washed and dressed Willie Lincoln after he died. A grieving Mrs. Lincoln asked Elizabeth to join her on travel: “I had one of my severe attacks,” she wrote the president. “If it had not been for Lizzie Keckley, I do not know what I should have done.” When Abraham Lincoln was shot, it was Keckly that Mary called to her side.

There is no way to justify the many evils of slavery or its role in White House history. Every one of these enslaved people, like millions of others across the young republic, were forced to build lives and work without the most basic human freedoms and dignity.

Our early presidents did little or nothing to improve the lives of the enslaved people around them. But long before Emancipation, whether they were treated as property or human beings, Black Americans have been making history at a White House they helped build. Juneteenth offers us a moment to remember their lives, and hear their voices.

Stewart D. McLaurin, a member of USA TODAY's Board of Contributors, is president of the White House Historical Association, a private nonprofit, nonpartisan organization founded by first lady Jacqueline Kennedy in 1961.

You can read diverse opinions from our Board of Contributors and other writers on the Opinion front page, on Twitter @usatodayopinion and in our daily Opinion newsletter. To respond to a column, submit a comment to letters@usatoday.com.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: How many presidents owned slaves? History of slavery in White House