White privilege may be real, but economic class is a bigger factor in driving inequality

Is white privilege real? It depends on how you define it.

Conservatives don't always want to acknowledge it, but on average life is better for you if you're white. I mean that statistically. In terms of life outcomes like poverty, educational attainment, proximity to violence, your average white person enjoys better outcomes than your average Black person (or other persons of color) because of myriad historical and contemporary factors.

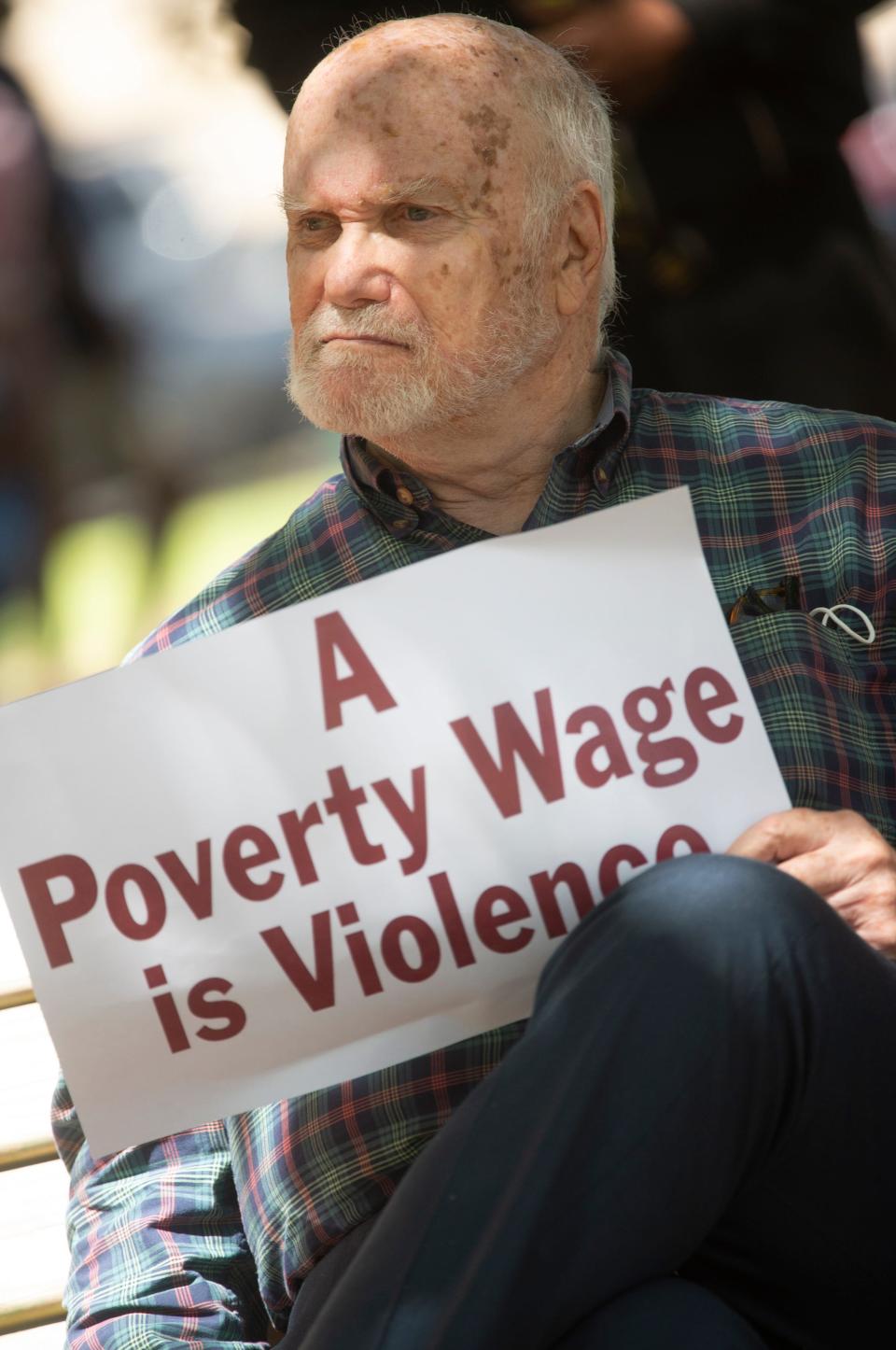

Yet, for millions of white people, the progressive emphasis on white privilege is offensive – and justifiably so.

For there are millions of poor white people in America for whom their skin color brings no advantage at all (and some number of well-to-do people of color for whom it does). This means that, while race still matters, we would be foolish not to consider privilege primarily in terms of class.

People in poverty are overlooked

There is a longstanding conversation over race in America that joins stream with a longstanding conversation over inequality. To many people on the left, one reinforces the other. But ultimately the way we talk about race does as much to obscure the plight of poor people of all colors in America as it does to reveal it.

Opinions in your inbox: Get exclusive access to our columnists and the best of our columns every day

The common narrative of racial reality asserts that for many people of color, the architecture of white supremacist society locks them into fixed cycles of poverty, violence and marginalization, diminishing their opportunity for success even when they do make it into the middle class and beyond. This general story line is most acute with respect to African Americans.

No modern example of the Black struggle is as salient as the phenomenon of mass incarceration. Black Americans represent 38% of the prison population (about three times our percentage of the general population), and even members of the Black middle class are more likely to go to jail than their white counterparts.

Why this is the case is always the subject of debate. But the debate is a foolish one.

Victim blaming versus system blaming

On such subjects, we are caught between what my friend Ian Rowe of the American Enterprise Institute and the Woodson Center refers to as the “blame the victim narrative” versus the “blame the system narrative.”

In the former, we blame poor people for their choices such as an unwillingness to get married, work a job and raise their children. In the latter, we blame systemic racism, the functioning or nonfunctioning of institutions designedly, or by default, punishing mostly people of color through policies that ensure incarceration, poverty, low-quality education and other social maladies.

Progressives try to cancel conservatives: How the right is fighting back

Each of these narratives is overly simplistic. The fixation on victim blaming obstructs the constructive work of institutional reform just as surely as obsession with system blaming undermines the community engagement work of grassroots, philanthropic and community-based organizations whose focus on personal responsibility and social uplift have been shown to work time and time again. (The Woodson Center is a prominent example.)

That is a subject for another column. What is relevant here is the little appreciated fact that, even while it is true that Black Americans represent a disproportionate share of the incarcerated population, what is far more disproportionate is the degree to which this population is grown from a single segment of the Black population – namely the Black poor.

There is a tendency among even many leading intellectuals to generalize about Black America in ways that obscure that fact.

This is a critique consistently leveled by Bertrand Cooper, an African American writer and analyst who focuses on issues of class and poverty and who grew up in abject poverty himself.

In a conversation with me, Cooper referenced a well-known essay by Ta-Nehisi Coates in The Atlantic magazine, "The Black Family in the Age of Mass Incarceration." Cooper noted that Coates does acknowledge that 8 out of 10 Black prisoners were in poverty before their incarceration.

Worse than Trump: How Biden bungled the job of leading America's economy

But, Cooper said: “Just a few paragraphs down, after highlighting how one class of Black people is producing all of the bodies, all of the suffering that activists are going to leverage to fight against incarceration, he switches to talking about Black people broadly and talking about how prison is affecting Black communities (and) talking about his own self as a Black person.”

Though it is true that Black middle-income earners are more likely than their white counterparts to live in poorer communities with higher crime and violence, the high rates of violent crime, drug abuse and incarceration often associated with Black America broadly are not a fact of life for African Americans in general. They are challenges faced by poor Black communities in particular.

Perhaps this suggests that targeted economic investment, reform and other interventions aimed at countering poverty and its affects could be pursued in a way that puts more distance between practical solutions and our decidedly impractical culture wars.

Cooper, as well as sociologists such as Patrick Sharkey, continues a lineage of class-based analysis of Black life that began perhaps with William Julius Wilson, who argued as far back as the mid 1970s that, following the civil rights movement, inequality of opportunity for Black Americans had become far less a direct function of race and much more a direct function of class.

Racial oppression created large Black underclass

This did not mean that the legacy of systemic racism was not to blame for the existence of such a large Black underclass. As Wilson wrote in his seminal work, "The Declining Significance of Race," “Racial oppression in the past created the huge black underclass. ... disadvantages were passed from generation to generation ... combined to insure it a permanent status.”

Nevertheless, Wilson also argued that failing to recognize the primacy of class as the driver of this marginalization was to misdiagnose the problem. Misdiagnosing a problem rarely leaves one in a position to solve it.

It is wrong to think that all African Americans share the same general struggle for equality. It is also wrong to think that white Americans share a universal position of privilege, even relative to most Black people.

I am the last of the Obama Republicans: But I still have hope for lasting change

In the book "Alienated America," author Timothy Carney tells a story of America’s collapsing rural and industrial communities – in particular those who voted for Donald Trump. Like Patrick Sharkey, who advocates for a “shift from a pure focus on social or economic status ... to a broader focus on the social environments surrounding families,” Carney sees the decline of community institutions (he focuses most on the church but this would include schools, local businesses, civic groups and more) as being both cause and effect of the condition of poverty that makes whole communities ripe for drug addiction, violence and deaths of despair.

As Carney wrote, “The same phenomenon we see in rural communities like Fremont County (Idaho) and Buchanan County (Virginia) is also visible in urban neighborhoods: When religious institutions shut down, the poor, working class, and middle class suffer as communities fray.”

Columnist Connie Schultz: How potholders got me thinking about racism, my father and the whitewashing of US history

These are the struggles of poor people (more specifically, poor people living in poor communities). We cannot wrestle with these problems or their solutions unless we are willing to confront the common denominator of class.

You will never hear me argue that race does not matter in America. But even much of the significance of race in the modern day equates to its correlation with matters of class.

Class also transcends race – both in terms of Black inequity and white privilege. Let's be committed enough to equality to remember this.

John Wood Jr. is a columnist for USA TODAY Opinion. He is national ambassador for Braver Angels, a former nominee for Congress, former vice chairman of the Republican Party of Los Angeles County, musical artist, and a noted writer and speaker on subjects including racial and political reconciliation. Follow him on Twitter: @JohnRWoodJr

You can read diverse opinions from our Board of Contributors and other writers on the Opinion front page, on Twitter @usatodayopinion and in our daily Opinion newsletter. To respond to a column, submit a comment to letters@usatoday.com.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: What progressives get wrong about white privilege