Whitewater became the center of a political firestorm. What residents think about the influx of immigrants

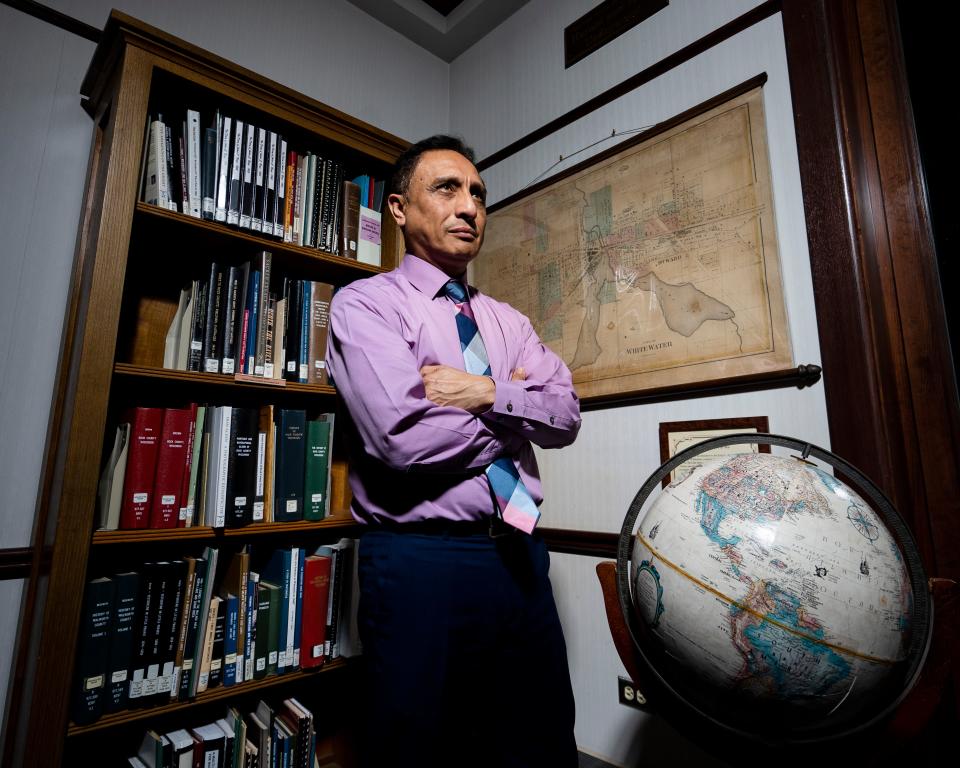

Jorge Islas-Martinez has dedicated much of his adult life to helping new immigrants find their way in Wisconsin.

He goes out of his way to help newcomers to Whitewater, said his brother, grocery store owner Luis Islas. He takes emergency calls at 10 p.m. from migrants who have been stopped by police, and drives others to Chicago for immigration court hearings.

"Mother Teresa of Calcutta — that's my brother in Whitewater," Islas said this week from his shop and taco restaurant, Tienda y Taqueria La Preferida, on the city's Main Street.

So as the political debate over an influx of about 800 to 1,000 new migrants to Whitewater continues to roil, longtime advocate Islas-Martinez finds himself incredulous at the tenor of the discussion. He's frustrated about rhetoric that he believes doesn't acknowledge migrants' humanity and divides the community.

"I've never felt so unwelcome until today," said Islas-Martinez, who is originally from Mexico and has lived in the U.S. for about three decades.

The new migrants, who are mainly from Nicaragua, have been drawn to Whitewater, a city of about 15,700 people, in the last two years for jobs on farms and in factories, several city and community leaders say. Many are following relatives and neighbors from their hometowns who are settling in the city. They are among the tens of thousands of Nicaraguans who have fled the country as authoritarian president Daniel Ortega's violent crackdown on dissent has instilled fear and ushered in economic instability.

In a letter this month, Whitewater police chief Dan Meyer and city manager John Weidl asked federal leaders for funding to add staff to handle the rise in population. It sparked a strong reaction from the community.

To some, Whitewater's challenges were the result of a crisis at the southern border. Others were frustrated that Whitewater was pulled into the political firestorm of American immigration policy. Still others acknowledged the city's difficulties while emphasizing its residents' generosity.

More: In Whitewater, an influx of immigrants has leaders determined to welcome newcomers, solve problems

Longtime advocate urges unity in city's response

Islas-Martinez is one of several in the community who offered their perspective to the Journal Sentinel.

He views terms such as "illegal immigrant" as derogatory. Local leaders who are working to solve the challenges of a larger migrant population should communicate respectfully to build bridges and create trust, he said.

"If there's a problem here in Whitewater, let's resolve it together. Let's talk about it. Not just attack," he said.

It's not easy to make a life in a new country, Islas-Martinez often reminds people. It takes time to learn a new language and adjust to the laws and customs of the land.

"It's a learning process," he said. "We need to be more receptive to that."

School board member, son of immigrants decries 'fear mongering'

Miguel Aranda, a member of Whitewater's school board, has also been frustrated about the way the migrants have been discussed by leaders. He sees it as a political ploy because it's an election year.

"Avoid the fear mongering," he said. "There is a humane way to do this. It’s frustrating that certain groups have gone the direction of fear, and just using this as a political weapon."

Aranda views the current conversation through his own experience. His father came from Mexico to do factory work in the area in the early 1990s alongside many other Mexican immigrants. Today's migrants also are seeking better opportunities, and they also find themselves at the center of the debate over border policies.

"It's repeating itself," Aranda said.

In food pantry volunteers, two diverging perspectives

At the Whitewater Community Food Pantry, two volunteers are grappling with their own political beliefs and what the migrants mean for the city.

They have not had first-hand experiences with the newcomers; the food pantry requires identification, proof of residence and proof of income. Because they may be paid under the table, undocumented individuals often do not have legitimate documents.

Jacki Hale, a member of the pantry's board for three decades, incorrectly believed that 1,000 people had been bused to Whitewater recently and did not know there had been a steady stream of arrivals over the last two years.

"The whole thing is a disaster. It's a joke. And why do we have to house all these people, and feed them? I don't get it. I don't know what it's going to do to the community," she said.

Volunteer Brad Stallings, a recent retiree who owned a construction business, knows of two migrant families living near his home. He will see the children waiting for the school bus. But he hasn't noted any uptick in crime or seen anything other than kids going to school and adults going to work.

"Those guys work their fannies off. They're just trying to get a better life," he said. "We do need to tighten the borders, but let's do it right."

A lifelong independent, Stallings said he was fed up with "all the political crap." In his view, politicians chose to make an example of Whitewater when they could have chosen other rural towns across Wisconsin.

"Pick a town, let's pick on them," he said.

Advocacy group encourages welcoming attitude

Marjorie Stoneman, of the volunteer and advocacy organization Whitewater Unites Lives, feels strongly that it is a community of generous people eager to help. Immigrants add diversity and enrich the community, she said. She's sad that the issue has been politicized.

"There are so many people who care about this issue and want to make sure people feel welcome," she said.

Whitewater Unites Lives members have marched in protests, supported cultural celebrations for local students and hosted a summer lunch program for children, among other events. In November, in response to a news conference involving elected and law enforcement officials, Stoneman and the group wrote a letter to express their dismay at the connections drawn between the drug trade and the recently arrived migrants.

"It is especially concerning to learn that some local leaders are perpetuating stereotypes by making public statements to the effect that immigrants are farm or factory workers by day and cocaine dealers by night," the letter reads, echoing a line from a public presentation Walworth County Sheriff Dave Gerber gave.

Owners of Mexican grocery stores have seen customer base evolve

Luis Islas, the owner of the Mexican grocery store and taco shop in downtown Whitewater, has seen a rise in customers from Nicaragua. The store's computer portal for wire transfers is popular as workers send money back home.

Islas came to the U.S. as a young adult to "create," he said, and he and his wife, Eva, have built a successful life for themselves and their four daughters. He has been frustrated with some migrants' lack of knowledge about traffic laws and what he views as a lack of interest in learning about American driving etiquette.

Once, he noticed someone parked the wrong way on the street. When Islas walked up to the man outside his car to tell him, the man said that people parked any direction in his home country.

It's about "getting used to the new rules," he said.

Both Islas and Juana Barajas, who owns a different Mexican grocery store down the street, have stocked more Central American food in their shops as more customers have been asking for it.

Barajas has added new brands of bread and snacks, fresh foods like cassava and taro, and blue lanyards and hats emblazoned with "Nicaragua."

She agrees that traffic laws must be respected. But she's upset with the number of Latinos she's seen pulled over for, in her view, no apparent reason.

Since undocumented immigrants can't obtain drivers licenses in Wisconsin, many drive without them and are regularly stopped and ticketed. More people paying to renew their licenses would bring the state more revenue, Barajas said.

Barajas has heard the connections some have made between the recently arrived migrants and crime. Hardworking immigrants shouldn't be lumped in with the troublemakers present in any population, she said.

"The Central Americans have come to be an excellent change here," she said in Spanish.

Barajas has run La Tienda Mexicana San Jose for 22 years. From its windows looking out onto Main Street, she's seen how Whitewater has evolved over time.

The storefronts across the street used to be empty, she said. Now there's a nail salon, a furniture shop, a clothing store and a taco joint, among other businesses. Many have Spanish names.

Immigrants have lifted up the town, she said.

This article originally appeared on Milwaukee Journal Sentinel: Whitewater residents respond to immigrant debate