‘It’s my whole life:’ Florida kidnap victims testify in trial of Haiti gang leader

Katiana Joseph was driving in the streets of Haiti in the summer of 2021 when two armed men on a bike stopped her. They jumped in her car, pointed guns at her and forced her to keep driving.

They stopped an hour later and told Joseph, who lives in Florida, that she had been kidnapped. The two men, members of one of Haiti’s kidnap gangs., took her phone, money, watch and jewelry. Another man then identified himself as Lanmò Sanjou, the No. 2 of the 400 Mawozo gang, whose name in English translates to “death doesn’t know when it’s coming.”

Sanjou dialed the last number on Joseph’s cell phone, placed it on speaker, and in Haitian Creole said to the person on the other end, “I have Katiana with me and you have to pay a ransom of $1 million.”

On Wednesday, Joseph recalled her August 2021 kidnapping while testifying in a Washington, D.C. federal courtroom, during the fifth day of a bench trial for notorious Haitian gang leader Germine “Yonyon” Joly.

“Talking to you about it... it’s hard,” she told U.S. District Judge John D. Bates, taking deep breaths, her voice wavering. “It’s my whole life.”

Joly, who ran 400 Mawozo from inside Haiti’s National Penitentiary, has been charged with 48 counts involving violations of U.S. export laws, weapons purchases and international money laundering. At the start of his trial, Joly waived for his right to have a jury hear his case and instead opted to have the judge decide.

On Friday, after Joly repeatedly refused to leave his cell and attend court proceedings, Bates issued an order warning him that the trial might continue despite his absence.

Joly is the highest-profile gang leader to be extradited to the United States in connection with the kidnapping of Americans. Though the abductions, including the kidnapping of 16 missionaries from an Ohio-based charity, are not part of the charges, the gang’s cycle of taking hostages for ransom is a key part of the U.S. government’s legal arguments. Laying out their weapons-smuggling case against Joly, U.S. prosecutors argue that his gang, whose territory extends close to the U.S. embassy in the Haitian capital and includes the main national road leading to the border with the Dominican Republic, transfers ransom proceeds to the U.S. to buy guns and then has them smuggled into Haiti.

In addition to Joly, prosecutors have identified three co-defendants, all Florida residents, who they say assisted him in making the illegal purchases from gun stores in Miami, Orlando and Apopka. Two of the defendants, Jocelyn Dor and Walder St. Louis, are expected to testify against Joly as part of their plea agreements. A third, Pompano Beach resident Eliande Tunis, who managed the gang’s arms and ammunition purchases, is awaiting sentencing after pleading guilty to all 48 counts in her indictment on the eve of the start of the trial.

Ahead of the trial, Joly’s lawyers tried unsuccessfully to block any mention of his affiliation to 400 Mawozo. During opening statements, his defense lawyer said while Joly had family members in the gang, he was a farmer who had devoted his life to helping his community. U.S. authorities presented testimony from investigators who raided the properties of his co-defendants and found receipts for gun purchases to Tunis and St. Louis, handwritten notes with Florida addresses and phones, and references to 7.62 mm bullets commonly used by AK-47s, among other weapons.

Investigators also found cash under a bed totaling $22,500, FBI Special Agent James Kaelin said as he described a raid the agency conducted in a Pompano Beach residence.

U.S. authorities have been reluctant to share how many U.S. citizens have fallen victims to Haiti’s kidnapping scourge. Publicly, they have asked Americans not to travel to Haiti and called for those in the country to leave. Privately, they admit that the country’s escalating gang crisis, which saw kidnappings rise by 83% in 2023 compared to the previous year, has overwhelmed the FBI’s Miami field office. In addition to foreigners and Haitian nationals, many of the gangs’ targets are Haitian Americans like Joseph, who while visiting family and friends in the Caribbean nation have found themselves held for days, if not weeks and months, and then forced to rely on others to negotiate their ransoms and help them pay.

Late Wednesday, the Archbishop of Port-au-Prince, Monsignor Max Leroy Mesidor, confirmed to the Miami Herald that six Roman Catholic nuns and two of their companions who had been abducted at gunpoint five days earlier had been freed by their captors. Still, at least one kidnapped victim, Douglas Pape, the son of well-known physician Dr. Jean William “Bill” Pape, remains in captivity nearly two months after his kidnapping on Nov. 28, 2023 and despite several ransom payments.

Abductions began to pick up in 2021 in the months before and after the assassination of Haiti’s president, Jovenel Moïse, on July 7, 2021. The victims include U.S. missionaries as well as Haitian nationals such as Wilkens Dicette, a local representative who was grabbed from inside a barbershop in Delmas, a suburb of Port-au-Prince.

He was eventually released, but not before his family in Haiti and South Florida spent 14 agonizing days trying to find out where he was, get police to open an investigation—which the family says was never done — and then try to raise the money to secure his release.

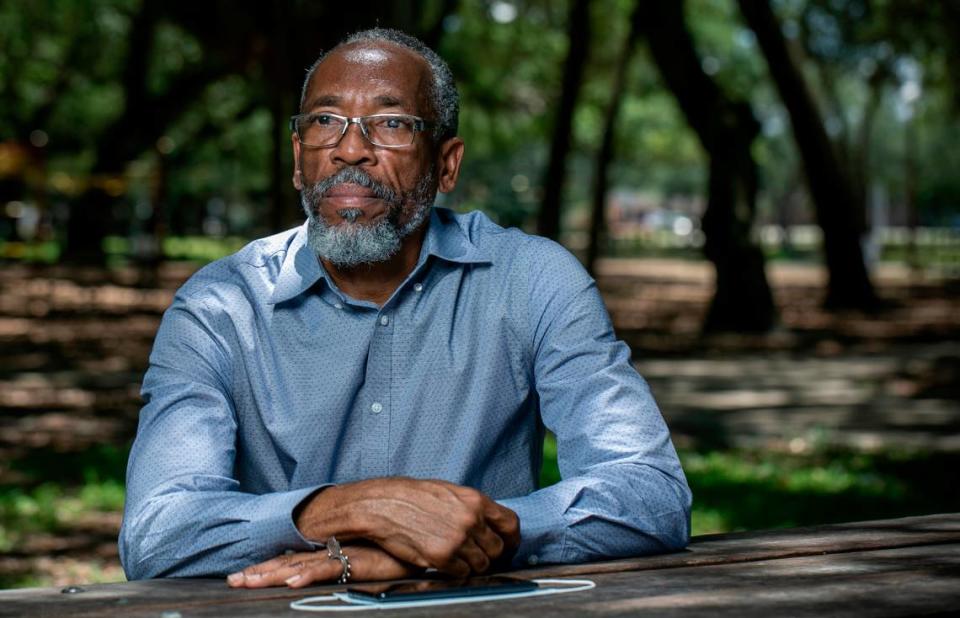

North Miami resident Emmanuel Louis-Jean, 60, was also a victim. He was taken hostage, he said, on Jan. 12, 2021, while parked on a Port-au-Prince street. His five captors appeared in a Toyota Rav4, which Louis-Jean said had been following him days earlier.

“I didn’t resist because I saw long guns, shot guns. They were heavily armed, some had two rifles with an M16,” he said. “They came with their guns and they opened my door. Two came to the back seat, one came to the front...the one who came to the driver’s side put a gun to my head and shoved me to the back.”

After being blindfolded, Louis-Jean said, the armed men ordered him to keep his head down as they drove him to Village de Dieu, an infamous kidnapping lair controlled by another gang leader on the FBI’s Wanted List, Izo 5 Segonn, also known as Johnson Alexandre.

“They said ‘We don’t have [orders] to kill you. We need to kidnap you for money,” Louis-Jean said. “I said, ‘Well, I need to cooperate so I won’t die.’ ”

Even now, Louis-Jean remains traumatized over his nine-day ordeal, saying he suffers from flashbacks thinking about how close he came to death. The experience, he said, has left a bitterness toward his native country and also made him fearful of visiting again.

During Tuesday’s trial, Joseph told the judge that she was placed in a room where there were other hostages. They were all Haitian.

One question that the gang did not ask, and she did not volunteer, Joseph said, was that she was an American. She realized that it would have things worse. Joseph said she was held in the room for nine days. After the ninth day they told they were releasing her.

Lanmò Sanjou, whose real name is Wilson Joseph and who is among seven gang leaders from five-Haiti based gangs wanted in the U.S. for the kidnapping of U.S. citizens, gave her a piece of paper with a number and said to call that to negotiate for her car later. She never did.

After her release, Joseph said she found out that local Haitians she knew had collected the equivalent of $50,000 in Haitian currency to pay for her release after the $1 million was negotiated down. Many of them did not even want the money back, she testified.

“Your health comes first; don’t even think about the money,” she said she was told, noting that to date, she has managed to pay back about $20,000.

After Joseph testified, prosecutors put on the stand another victim of the 400 Mawozo gang, Jeanty Louis, a U.S. veteran whose abduction was publicized on Haitian radio. Louis, an ex U.S. Marine who works as a security specialist for an international nongovernmental organization in Haiti, splits his time between Miami and Port-au-Prince, where he was born.

On Aug. 27, 2021 he was kidnapped by seven gang members carrying assault rifles. During the kidnapping, one of the gang members accidentally shot himself in the foot, he recalled, telling the judge that upon being taken hostage, his phone, wallet, gun and car were confiscated, and his hands and arms tied.

The kidnappers made an initial stop, and he overheard them saying they had to wait because police patrols were in the area. Upon arriving at another destination, Jeanty said, he was confronted by Lanmò Sanjou, whom he recognized through his security work and who introduced himself by name.

Sanjou asked him to call a relative to negotiate his release. Jeanty was then taken to a house with two rooms, divided by something similar to a drywall. In his room, Jeanty said, was a fellow hostage, a Haitian. In the other room was a group of five Haitian hostages.

On the second day of his captivity, Jeanty said, Sanjou appeared again and asked him and the other hostages to call their relatives and demanded that the ransoms be paid in cash. Sanjou said also spoke about Jeanty’s U.S. citizenship and time in the U.S military, which he had been alerted to from radio reports.

The gang’s operations, Jeanty testified, seemed quite organized: They had multiple locations where they held hostages and referred to them by numbers. In his own location, there was a person in charge and another who took care of logistics like bringing toothbrushes, soap, water or medicines. The guards all carried assault rifles like AR-15s and M14s, Jeanty said, along with shotguns, and they worked in shifts. There was clearly a hierarchy, he testified.

On the fifth day, Jeanty said, he was pulled out of the room. Sanjou informed him that he was being released without a ransom. At 11 p.m., gang members asked him to get dressed. His vehicle was outside. They then drove him to another where all of confiscated items besides his gun were returned to him.

Jeanty said a man with a green notebook containing names and a record of confiscated items matched each item up and asked him to confirm that he got everything. He was then driven to another site where Sanjou personally met him. His capture, Sanjou told him, had been a “misunderstanding.”

Asked what the gang leader meant, Jeanty said Sanjou did not elaborate. He also said he doesn’t know why he was released without a ransom.

Jeanty says the gang leader then gave him his cell number and asked him to give him a call if he ever had any problems. When Jeanty asked about his gun, Sanjou replied by asking him if he would’ve returned a firearm if he, Jeanty, were in his shoes.

The day after his release, Jeanty was interviewed by a law enforcement official at the U.S. embassy. He arrived in the U.S. a week later, he said, where he was then interviewed by the FBI.