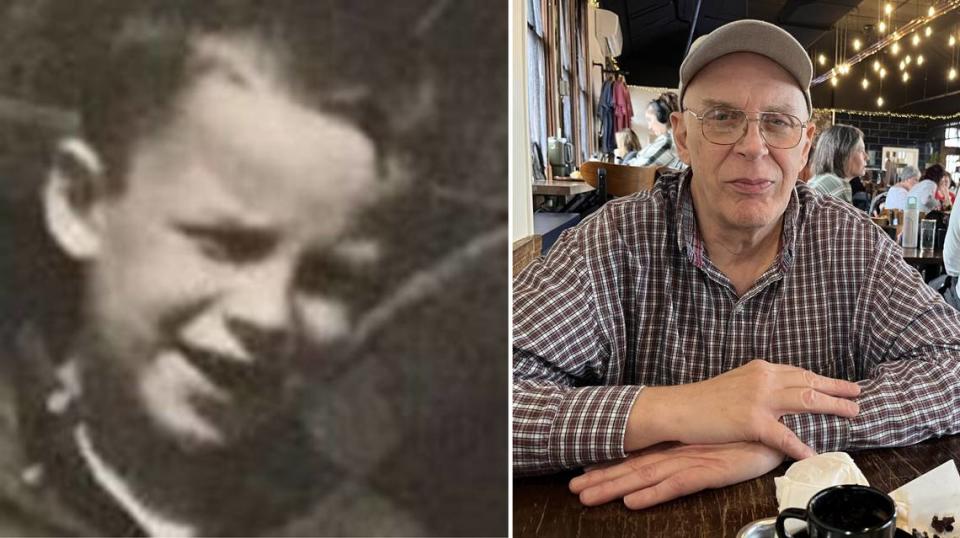

‘My whole life was ruined,’ says Belleville man who alleges sexual abuse as a Boy Scout

James Eddings freely admits that he spent most of his life sabotaging his own chances for success and happiness.

He cites a long list of problems, starting with school fights and expulsions and continuing with a general military discharge, job instability, three divorces, poverty, homelessness, arrests for bad check-writing and burglary, anger-management issues, low self-esteem, a nervous breakdown, suicide attempts and stays in mental hospitals.

Eddings, 65, of unincorporated Belleville, said he has felt some measure of peace since 2004, when a West Coast psychiatrist helped him uncover repressed memories of child sexual abuse in the 1960s and early ‘70s at the hands of three Boy Scout leaders in East St. Louis.

“I knew it was there,” he said last month. “I just didn’t want to admit it to myself or anybody else.”

Eddings is one of more than 80,000 men in the United States expected to receive settlements from a $2.4 billion fund set up by the Boy Scouts of America for victims of child sexual abuse.

He believes there are many more victims, dead and alive, who have been too afraid to come forward because of the social stigma and how it could negatively affect their lives.

Eddings said he’s going public because he wants the world to know what happened to him and other Boy Scouts and the legal system to hold the organization and its enablers accountable.

“We’re still being victimized,” he said. “The Boy Scouts right now are lobbying state and federal legislators to limit future liability for child sexual abuse involving the BSA (under the guise of ‘bankruptcy reform’).”

Boy Scouts bankruptcy

The Boy Scouts filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy three years ago in U.S. Bankruptcy Court for the District of Delaware after facing lawsuits all over the country alleging child sexual abuse by troop leaders. The settlement fund was part of a financial restructuring plan completed in April.

The organization also put in place safety protocols, including background checks for staff and volunteers, mandatory youth training and a ban on one-on-one interactions between adults and children.

“While the BSA understands that nothing it does as an organization will undo the pain survivors have endured, the organization will continue listening to them, evaluating its youth protection procedures, and working every day to make a positive impact on young people and communities across the country,” its website states.

East St. Louis is in the Greater St. Louis Council of the Boy Scouts. Director of Marketing Dave Chambliss referred questions about Eddings’ case to the organization’s National Media Relations office.

“We do not comment on individual claimants with whom we are in litigation,” the office stated in an email. “Please direct your questions to their legal counsel or the Scouting Settlement Trust.”

Eddings is being represented by Ben Watson, an attorney with the Seattle firm Pfau Cochran Vertetis Amala. Watson is part of a team that specializes in abuse claims against entities such as the Boy Scouts and Catholic Church. He verified that Eddings is a client but declined further comment.

The team is now gathering information from claimants and poring over records that the Boy Scouts have begun to release under the restructuring plan, according to a settlement update emailed to Eddings on Oct. 19 by Watson’s colleague, Victor Nappo.

“As you can imagine, we are spending a great deal of time evaluating the newly produced records, which are extensive and should have been produced many months ago,” Nappo wrote. “We are also trying to determine the full extent of what records are still missing.”

Eddings said he’s been told that he will get a minimum of $45,000 from the settlement fund, which he calls an “insult” given that some people receive hundreds of thousands of dollars through workers’ compensation after suffering permanent injuries on the job.

“My whole life was ruined (by child sexual abuse),” he said. “I have all this retrospective and insight now, but I’m 65 years old, and I’m doing something now that I should have been doing 25 years ago.”

Eddings was referring to his passion for producing electronic music.

‘Dysfunctional’ family

Eddings grew up in what he describes as a “dysfunctional” family of seven in East St. Louis. His father, the late Robert Eddings, worked on the railroad. His mother, the late Bonnie Eddings, was a nurse, homemaker and precinct committeewoman who reared five children.

James Eddings said he was a hyperactive kid with poor vision that didn’t get corrected until he enlisted in the U.S. Air Force, and that he often was bullied at the former St. Philip Catholic Grade School in East St. Louis and metro-east high schools he attended before getting a GED.

He said he was about 6 years old when he was first molested by a teenage friend of the family and that the abuse continued after he joined Boy Scout Troop 22 at age 8 because the teenager had become an assistant troop leader who drove him home from meetings.

“He used to rape me in his parents’ basement,” Eddings said.

Eddings said he was also molested by two adult leaders during campouts at Clearwater Lake in Missouri and elsewhere. He’s not naming any of the three men due to pending litigation.

Eddings said his mother took him out of Boy Scouts at age 12 after he came home from a meeting with welts on his body from running a leader-supervised “gauntlet” that involved boys slapping him with belts as a punishment for misbehavior.

“It was to make a man out of you, to toughen you up,” he said.

Life far from home

Eddings spent most of his adult life in California, Oregon and Washington. He said he moved back to the metro east in 2021 because he was in poor health and longed to return “home.” He’s been diagnosed with chronic lymphocytic leukemia, a form of cancer.

Over the years, Eddings earned an associate’s degree in radio communications and worked a variety of jobs, including as a truck driver, carpenter, orchard caretaker and radio personality. He said he became eligible for government disability payments after falling while trimming a tree in 1988 and incurring a spinal injury that required multiple surgeries.

Eddings said he began undergoing psychotherapy in the mid-1980s after having a nervous breakdown and being sent to a mental hospital, and that this led to a “breakthrough” in 2004 that brought back memories of child sexual abuse in the Boy Scouts.

“(A psychiatrist) started demanding that I tell him who had abused me,” he said. “He wouldn’t take no for an answer. I love that man. He’s retired now and living in Hawaii. I still talk to him once a year.”

Eddings said he considered joining a class-action lawsuit against the Boy Scouts with other alleged victims of child sexual abuse before the organization filed for bankruptcy in 2020 but decided against it.

He is estranged from his family, including his four siblings and one living child (another one died), and he hasn’t kept in touch with metro-east friends from his childhood or teenage years.

He remains close friends with Chris Guettler, 57, who works in the wholesale furniture business near Portland, Oregon. They met about 25 years ago, when Eddings was hitchhiking and Guettler gave him a ride.

Guettler describes him as a “super smart guy” who knows a lot about politics and other subjects because of the time he spent educating himself. He said Eddings told him more than 10 years ago about being sexually abused as a Boy Scout, well before the organization filed for bankruptcy, although they didn’t discuss details of what happened.

“I never had a situation where I was abused, so I have no idea how that affects people, and I’ve never done any research on it,” Guettler said. “But to carry that around and not be able to tell people ... That’s something no child should have to go through, and it has to do damage to someone’s life.”