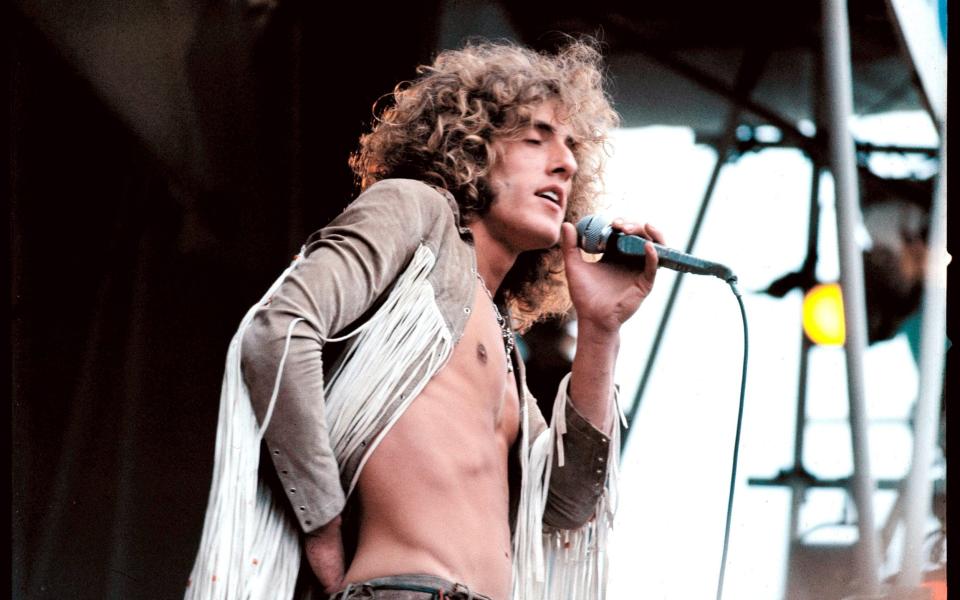

The Who's Roger Daltrey: 'If we'd all got on, the music would've been awful'

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

“Like roaring into a thick fog at 300 miles an hour,” is how Roger Daltrey describes his imminent return to live performance for the first time in months. “Somewhere in there is a load of gigs that we hope to get to. It won’t be easy. But I’m a singer. Gotta use it or lose it.”

Daltrey is embarking on a short solo tour next month, backed by the Who’s live band. “There’s two purposes: one is to keep me singing, fit, out of the house,” he says. “And secondly, to get our road crew and musicians working, because they’ve had a tough 18 months.”

He is furious at the Government for its failure to provide adequate support and insurance for the music business throughout the pandemic; now, he’s stumping up his own cash for a tour on which he fears, given the precariousness of the Covid situation, “they could pull the plug any minute”. He grumbles enthusiastically, swears colourfully. “Nothing in the world makes sense to me any more,” he says. “We’re being run by idiots.”

In the end, he can only laugh. “What do you do? You roll yourself into a ball and say life’s over, or you push yourself out there. If we all take care of each other, we’ll be all right.”

Daltrey is a fascinating character, a charismatic multimillionaire veteran rock superstar with the belligerent humour of a London cabbie. He has trenchant opinions about everything, expressed in pungent language delivered in an accent that’s all nasal tones and dropped aitches.

During a couple of lively hours of conversation, he makes brusque, argumentative digressions into politics, taxation, history, charity, Covid, unions, wages and climate change. And, of course, Brexit, of which Daltrey has been quite an isolated voice of support within an industry angered by its impact on European touring.

“Brexit hasn’t f----- touring,” he insists. “We knew it would be difficult, but it will sort itself out. I still haven’t changed my mind that we did the right thing. Brussels is just bureaucracy gone mad!”

He is not impressed with the “woke generation”, either. “Do they really think eradicating history – toppling statues and burning books – is going to solve anything? You should take the past as an example to make the point of why something was wrong. Not burn things, or disappear things, because then it can all happen again. The last people to burn books were the Nazis. And I should suggest it’s taken on a very similar slant…”

Compact and lithe, Daltrey, who turned 77 in March, retains a restless physical energy but his hair is sandy grey, he wears prescription sunglasses and has two discreet hearing aids.

“It’s brutal going deaf,” he says, briefly removing them and laying them on the table. “If I take these out, everything’s a mumble. The top end has completely gone. If you’re in a roomful of people, it’s just a cacophony, horrendous.

“The Who were the innovators of loud – more amps, more volume. We thought we were being clever. We were being stupid. If I could change one thing now, I’d rather not be the innovators of loud, and have my hearing back.”

A lump on his jaw, from a recent tooth implant, inspires another grumpy diatribe about how a post-war influx to the NHS of badly trained Australian dentists ruined British teeth for his entire generation. “Ah, the joys of getting old,” grimaces the man who famously sang that he hoped he’d die before that ever happened. “Who knows when the end is going to be? But it will be! Life is a terminal illness. Get over it! We seem to be living in fear and we can’t do that; we’ve got to get out there and work.”

Daltrey’s man-of-the-people quality is reinforced by the setting for our interview, the back garden of his two-storey, semi-detached home on a quiet residential street in Chiswick. It is a nice house, with a tidy front yard barely big enough to accommodate his four-wheel drive, but it is no rock star folly. While we chat, Daltrey’s wife, Heather, ferries teas and coffees from a well-appointed kitchen. “When I got a bit of dosh, I bought this instead of a pension,” he says. “It’s somewhere to hang out in London.”

The house isn’t so far from either the old Acton County Grammar School, where Daltrey met Pete Townshend and John Entwistle – with whom he would form the band known first as the Detours, then as the Who – or the sheet metal factory in Shepherd’s Bush where he worked after he was expelled, aged 15.

He was raised in a terraced house nearby, which he also now owns. “The first thing you had to do if you made any money in those days was buy your mum a house,” he says. When his mother died, “she left it to me, so I got it back. That’s where the Who used to rehearse. It’s like a shrine to me.”

Since 1970, Daltrey has also occupied Holmshurst Manor, a Jacobean pile in East Sussex, which incorporates a working farm and Lakedown trout fishery. He has recently encountered problems gaining planning permission to install a microbrewery – something else about which he complains at length – but he pronounces himself pleased with his range of Lakedown beers. “It’s bloody good stuff. We can’t make enough of it.”

As the Who’s frontman, Daltrey became known for balancing raging machismo with spiritual sensitivity, although he points out that much of his aggressive onstage persona stems from his interpretation of Townshend’s lyrics. “The words carry their own power,” he says. “You have to rise to them.”

In their early days, in the 1960s, the band were very much Daltrey’s, before middle-class art student Townshend’s cerebral songwriting and conceptual innovations made the guitarist the de facto creative leader.

“Pete always says the Who was a gang,” notes Daltrey. “I suppose it was in a way, for him, because he’d been bullied at school. So Pete felt kind of protected being in a band with me, because my reputation preceded me. I’m not really a violent person, but if someone tried to bully me, I hit back. That’s a street thing. They soon learn to leave you alone.”

The Who’s colourful history is marked by personality struggles. When I ask whom Daltrey was closest to, he shrugs. “Believe it or not, none of them, really. I think if we’d all got on, the music would have been awful. The songs come out of misery. They’re quite aggressive. Something about the fact that we were who we were made it work.”

And work it did – from the nihilistic rallying cry of My Generation in 1965, through dizzying art rock singles such as Substitute, I’m a Boy, Pictures of Lily and I Can See for Miles, to their two pioneering rock operas, Tommy (1969) and Quadrophenia (1973), and the successful merging of guitar power with synthesisers and sequencers on Who’s Next (1971) and Who Are You (1978), which still represent a peak for hard rock. The Who remain one of the most influential bands in history.

Two members died along the way – manic drummer Keith Moon in 1978 and virtuoso bassist Entwistle in 2002 – but the surviving duo soldier on, performing with an expanded band capable of fully realising Townshend’s sprawling musical vision, and still releasing original music, including a fantastic new album, Who, in 2019.

“We were gifted to have our relationships,” says Daltrey. “I’ve never believed those things happen by accident. When you think of the 1960s – the Beatles, the Stones, the Who, Zeppelin, Floyd – there’s something about that era, an energy and creativity going beyond coincidence. And if you’re given a gift, you have to push it as far as you can.”

This leads Daltrey to consider the recent death of Charlie Watts, the Rolling Stones’ drummer. “They’ve got to keep going, because when they play, Charlie will be back, he will reverberate for ever in that music. We’ve done it twice, with Keith and John. They created the music and they will always be in it. And they don’t go away.”

Not that Daltrey is sentimental about his bandmates. “He is a miserable git!” he says of Townshend, laughing. “But he will tell you he’s made a fortune out of misery, so if he started to have fun, he probably would never write another note.”

Daltrey admits to being baffled by Townshend’s frequent assertions that it was no fun being in the Who. “Every photo I see of us doing something together in those old years, we’re all laughing our heads off! No fun, Pete? Well, who’s that with his arms around Moony, grinning like a loon?”

Entwistle is given even shorter shrift. “John was a selfish man,” says Daltrey of the bassist, who died in 2002, at the age of 57, after suffering a cocaine-induced heart attack while in bed with a stripper before the opening date of a US tour that had been organised specifically to help Entwistle out of debt. “If you got him on the drugs, you know, with Colombian marching powder up his nose, he could be great fun,” says Daltrey. “But without that he was as dull as dishwater.” He says Entwistle rarely offered input in the studio. While Daltrey and Townshend would try to push things forward musically, “nothing came out of John. It was kind of weird, like a vacuum”.

Drummer Keith Moon was more complex. Daltrey describes him as “the funniest man I’ve ever met, also the saddest, also the most kind, also the most spiteful, he was everything. The most of the most.”

Moon died of an accidental drug overdose aged 32, in 1978. “My only regret in the band is that we did waste those golden years when we were so red hot, we were on fire. I think we would have kept Moony alive if we toured more. We stopped for two years [1977 and 1978]. And where was he going to put all that energy? He went into self-destruct.”

While other band members spun out of control (even Townshend briefly struggled with heroin and alcohol problems), Daltrey stayed away from hard drugs and drank only in moderation. “I only ever wanted to be a singer, and you’ve got to stay healthy,” he says. “Most of my power comes from my chest.”

He says the 1975 filming of Tommy – the Who’s rock opera about a deaf, dumb and blind kid who becomes the spiritual leader of a pinball cult – had a huge impact on him. “We worked with a lot of really bodily challenged people – as you would say today. In those days, we would say disabled. And I learnt so much from their humility, their dignity. It was an incredibly humbling experience to see these people just trying to get any kind of normality out of this wonderful life that we’ve all been given. And you’re just destroying it with all this other bolt-on crap! I’ll never forget that period. It was a really interesting, emotional learning curve. It was kind of lovely.”

Daltrey has a reputation as one of rock’s good guys. He has been a patron of the Teenage Cancer Trust since it formed in 1990, organising an annual concert series that has raised more than £20 million so far. He has been married to Heather, his second wife, since 1971. He did not meet some of his eight children – from two marriages and some brief affairs in the 1960s – until they were adults, but he welcomed them all into his family, along with in-laws and grandchildren: “the whole tribe,” as he puts it.

He is adamant that the Who will return to the road in 2022. “I love to sing. I love to connect. That’s my mission in life, to find the emotion in words and melodies and be a connecting rod to the audience.” He pauses. “I sing my life,” he says. “Who knows how long it will last? I’ll keep singing as long as I can.”

Nevertheless, he insists: “I can’t see myself as a rock star. I’m still the kid that was slung out of school at 15. I’ll always be that person. I am not putting myself on any bloody pedestal. I’ve seen people on pedestals; they usually end up falling off and breaking their bones. It is not a good place to be.”

Roger Daltrey’s Who Was I tour starts at Birmingham Symphony Hall on Nov 7. Details: thewho.com