'Whose daughter is next?' Missing, slain Native people need officials to do more, families say

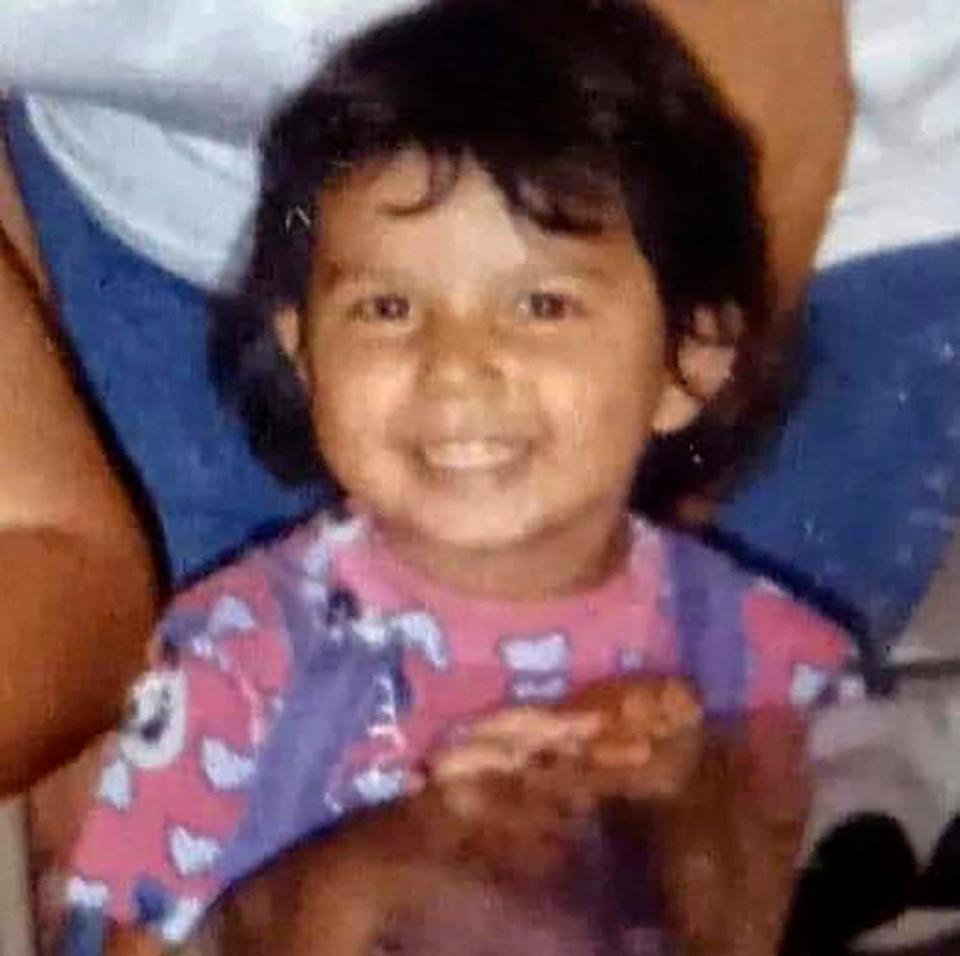

Skye was Alecia Onzahwah’s quiet child, always compassionate and funny even when she was struggling in life.

Her killing has pushed Onzahwah to speak out and search for answers she believes investigators never tried to find.

“We’ve always been called the Indian ‘issue,’” said Onzahwah, who is Absentee Shawnee. “We are not an issue. Systemic racism is the issue. We are a people.”

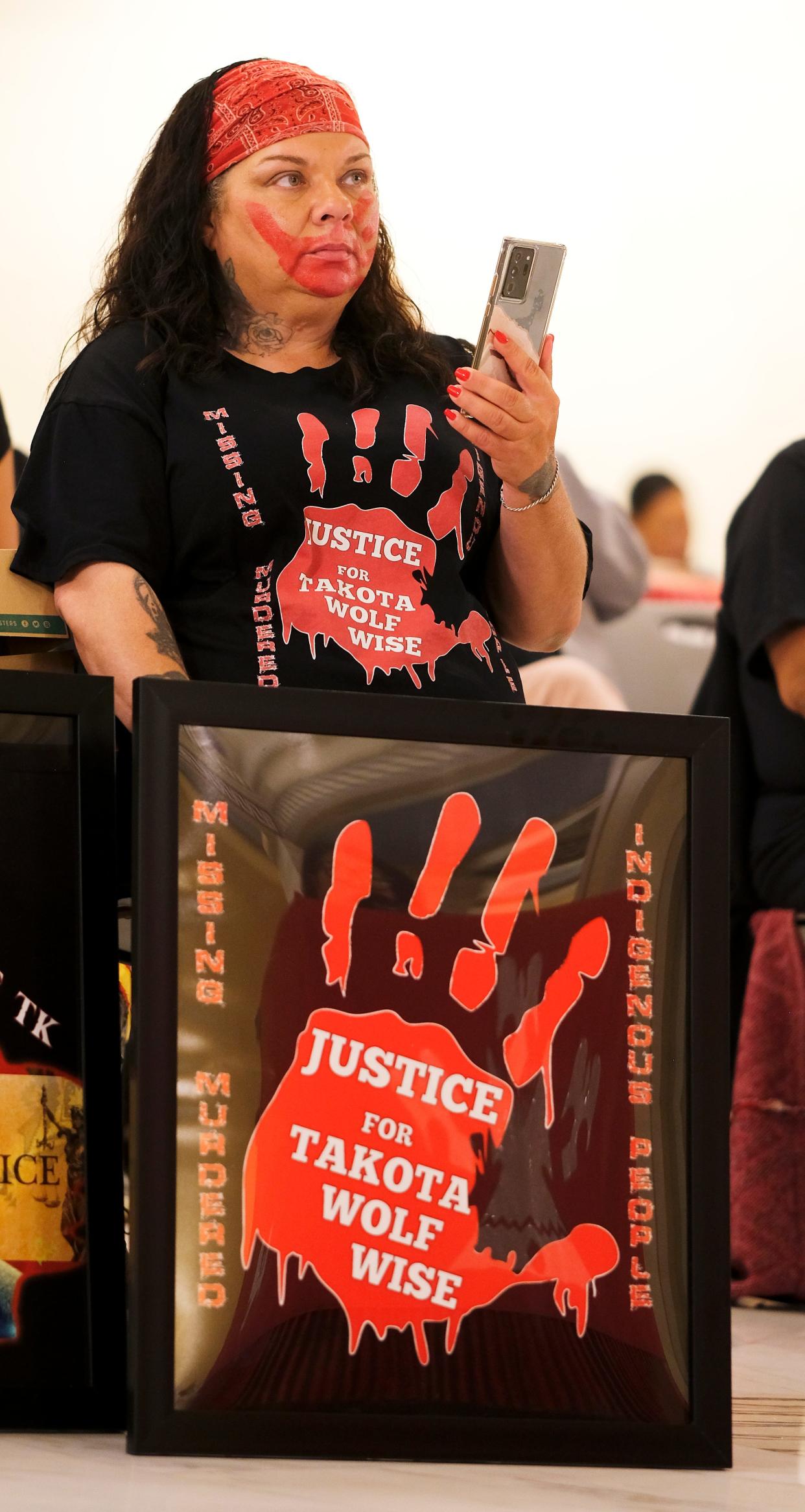

The crisis of missing and murdered Indigenous people came under the spotlight Thursday at events organized throughout the U.S. and Canada.

Onzahwah was among the 250 people who came together inside the Oklahoma state Capitol to share stories about their relatives and press lawmakers to do more. Many members of Onzahwah's family wore white T-shirts printed with Skye's name and a red handprint.

'My daughter is missing': New laws fail to shield Indigenous women from higher murder rates

Skye Jim was 30 years old. She had five children. She had a job she loved as a casino cage manager but was laid off at the start of the pandemic. She was Sac and Fox, Absentee Shawnee and Kickapoo.

She died after she was hit by a car on a rural road beneath Interstate 40 in Pottawatomie County. Onzahwah is focused on what happened in the moments and hours leading up to that.

Investigators told her in October the case was closed, she said.

“No one should have to go through this,” said Onzahwah, of Tecumseh.

Indigenous women face more violence, disappear more often

More than four in five Indigenous women will experience violence during their lifetimes, and two in five will have faced violence in the past year.

Native women living on reservations are 10 times more likely to be killed than the average U.S. woman, and homicide is the third-leading cause of death among all Native women, regardless of where they live.

Native people also go missing at disproportionate rates. Because of gaps in federal law enforcement databases, it’s impossible to know how many remain unaccounted for. The Bureau of Indian Affairs believes the number is close to 4,200 people.

Questions about law enforcement jurisdiction can hamper or stall the investigations in many parts of the U.S.

“Missing women are the center of our tribal nations,” said Cindy Famero, of Lawton, who leads the Warrior Woman Society, a prevention group. “Without them, we don’t have our center. If we don’t have our center, we don’t have our roots.”

Protecting victims: Tribal court power over non-Natives now covers sex assault, stalking

Growing public awareness of the crisis has spurred federal and state officials to take some steps aimed at closing cases and improving safety in Indian Country.

Three Oklahomans on commission seeking to investigate, improve systemic issues

President Joe Biden proclaimed Thursday to be National Missing Or Murdered Indigenous Persons Awareness Day.

Interior Secretary Deb Haaland created a Bureau of Indian Affairs unit last year devoted to trying to close the unsolved cases. Haaland, who is Laguna Pueblo, became Interior secretary last year after serving in Congress as a New Mexico congresswoman. In that role, she pushed federal officials to investigate the cases of missing and murdered Indigenous people and to form a commission dedicated to trying to fix systemic issues.

She announced the 37 members of the commission Thursday, including three from Oklahoma: State Bureau of Investigation special agent Dale Fine Jr.; Cherokee Nation Marshal Service investigator Shawnna Roach; and Carmen Harvie, president of the Oklahoma Missing or Murdered Indigenous Persons statewide chapter.

Indian Country jurisdiction: Oklahoma tribal leaders hopeful after Supreme Court hearing linked to McGirt decision

The group is one of several throughout Oklahoma dedicated to helping Native families find their missing relatives. They were all represented at the state Capitol on Thursday. OSBI and BIA investigators also attended, as did a handful of state lawmakers.

The hours-long event was held in the second floor rotunda near the office of Gov. Kevin Stitt.

In 2021, Stitt signed Ida’s Law, which directs the OSBI to work with federal officials to fund and create an office dedicated to investigating the killings and disappearances Indigenous people.

The law is named after Ida Beard, who went missing from El Reno in 2015. She belongs to the Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes.

But many people gathered on Thursday said Ida’s Law is not enough to protect Native women and to ensure their disappearances and deaths are investigated.

Famero, who also helps lead the Oklahoma MMIP chapter, said she believes state authorities could take a basic first step.

“They need to build connections with us,” said Famero, who is Comanche and Lakota. “Reach out to us … They don’t ever call back.”

Rep. Jacob Rosecrants, D-Norman, agreed lawmakers need to do more. He cited state funding for Ida’s Law, which wasn’t included in the 2021 legislation.

After her daughter’s death, Onzahwah learned how difficult it was to navigate through law enforcement channels and other resources available to families.

She created The Skye Woman Project, a website to help other families. It’s important to share her daughter’s story because doing so could save someone else, she said.

“Whose daughter is next?” she said. “That’s what I fear — whose daughter is next.”

Molly Young covers Indigenous affairs for the USA Today Network's Sunbelt Region. Reach her at mollyyoung@gannett.com or 405-347-3534.

This article originally appeared on Oklahoman: Families rally to bring awareness to missing, murdered Indigenous women