Why 100,000 people a year trek to the Rothko Chapel, the world’s most ‘challenging’ art venue

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

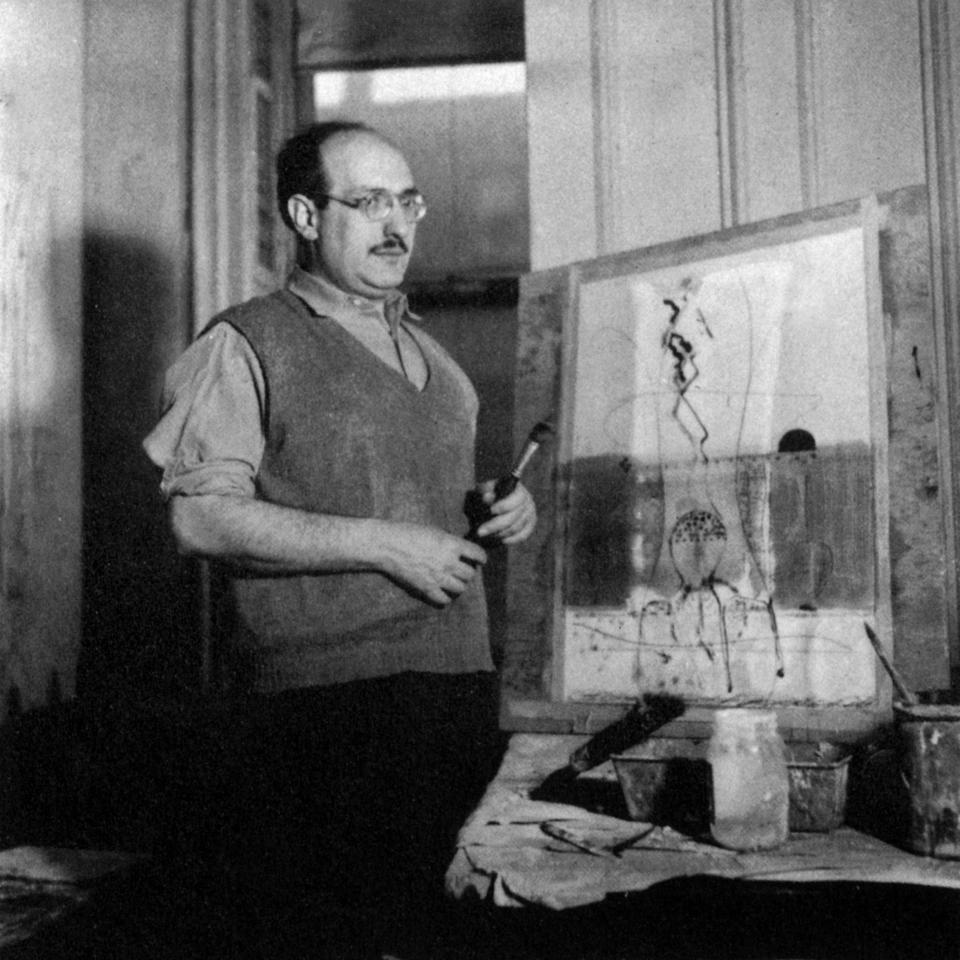

This week marks the 50th anniversary of one of the great artworks of the 20th century. Not that its creator ever got to see it unveiled. The work in question is the Rothko Chapel in Houston, Texas, which opened its doors on February 26 1971. It was designed by the eponymous American painter, Mark Rothko, who also provided 14 of his trademark abstract canvases for the interior.

Visitors over the past half-century have included the Dalai Lama and Nelson Mandela (shortly after his release from prison) but not Rothko himself – who committed suicide in 1970, aged 66.

“The chapel was his magnum opus,” the artist’s son, Christopher Rothko, tells me. “It was the ultimate expression of everything he’d done in his career leading up to it.”

Located in the leafy Houston neighbourhood of Montrose, the chapel was commissioned by local philanthropists John and Dominique de Menil in 1964. They intended it as a venue for those of any religion – and also no religion – “in search of peace, meditation and a more intense consciousness”.

Though based in New York, Rothko seemed the perfect artist to employ. Along with Jackson Pollock, he represented the pinnacle of the Abstract Expressionist movement in the years after the Second World War. However, where Pollock is renowned for his all-action splatters, Rothko’s painting is about contemplation.

His pictures – the most expensive of which sold for £54 million in 2012 – typically feature rectangles of different colours and sizes seeming to hover over infinite space. They provide a sense of awe without specific religious connotations.

“He wanted to engage viewers in a kind of conversation about who they were and what they were experiencing,” says Christopher. “The chapel was a dream commission in that sense, a Gesamtkunstwerk that allowed him to set the terms of the conversation himself. It’s a quiet space, where visitors can stay at length – as opposed to the forced march you get when seeing art in museums or galleries”.

Rothko’s all-enveloping paintings (three triptychs and five individual works, none less than 11ft tall) are mostly black and dark purple. They’re hung on the octagonal chapel’s grey walls in a windowless, dimly skylit interior. The sombre colour scheme helps create exactly the meditative ambience the de Menils sought.

Now 57, Christopher visited his father’s Manhattan studio frequently as a boy, though he says his earliest memory of it dates to around 1969, “by which time [Rothko] had finished work on the chapel paintings. They must have been standing to one side somewhere, and I had no idea what they were”.

Rothko hailed from a family of Latvian Jews but wasn’t religious himself. In contrast to Michelangelo, who painted the Sistine Chapel ceiling on scaffolding in situ, he never actually visited Houston. He just created a mock-up of the future chapel in his studio.

Christopher – a qualified psychologist who now dedicates himself to organising exhibitions of his father’s work – had never visited Houston either before the mid-1990s. “I was unprepared for how intense that [first] experience would be,” he says. “I spent two hours alone in the chapel one morning, before it opened. Given the personal layer of my relationship with my father, it was almost too much.”

Christopher has served on the Rothko Chapel Board of Directors since 2004. Around 100,000 people pass through the doors annually (or, at least, they did pre-Covid) – many of them art pilgrims from around the world, others from closer to Houston attending weddings, memorials and prayer services or seeking a moment of private reflection.

The chapel also hosts regular inter-faith meetings, plus lectures and symposia on human rights, all as part of its mission “to work towards a culture of mutual understanding”. How important does Christopher think such a mission is at a time when America’s so divided?

“Things are fractious in the country, it’s true, but that’s nothing new. The mistrust of others is something that can only be dissipated when you bring people together and they see their common human bonds. The chapel works hard at that every day”.

After 18 months closed, the venue reopened – to socially distanced visits – in September last year, following the first part of a $30 million restoration. One of the changes was to tweak the skylight and allow greater, more even illumination.

Christopher is pleased. The chapel paintings were Rothko’s last big project, and are much darker than the bright canvases from earlier in his career: two facts that have helped perpetuate a myth that they were the product of a deeply troubled soul. This, his son says, is simply untrue.

“He actually carried on painting for three full years after finishing the chapel works. The place is challenging in its darkness, but spend a little time in there – especially since the restoration – and colour really starts to emerge from those paintings”.

It speaks, in other words, of hope, not despair.

From tonight until Sunday, a series of live-streamed events are being held to mark the Rothko Chapel’s 50th anniversary. Info: rothkochapel.org