Why Is a 12th Century Muslim Jurist Depicted in a 16th Century Pope’s Library?

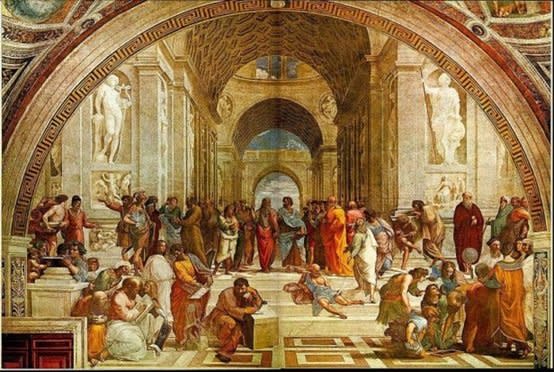

The School of Athens is a fresco by Italian Renaissance artist Raphael as part of the artist's commission to decorate the rooms in the Apostolic Palace in the Vatican.

Leonardo Da Vinci, Michelangelo and Raphael were the three artistic giant geniuses of the Italian High Renaissance. “The School of Athens,” painted by Raphael from 1510-1511 in the private library of Pope Julius II (1503-1513), represents the essence of that aesthetics. Namely, the primary interest of the artists was no longer painting what they saw in nature, visual reality, but rather depicting ideal reality, imagined reality, ultimate reality.

The architectural setting is an imagined, ideal, ancient Roman temple, barrel-vaulted incorporating an arch. The primary subject of the painting is historical intellectuals engaged in discussion. In the center Plato points upward to indicate his theory of ideal forms, whereas Aristotle points downward to indicate his study of everything earthly. Socrates is on the left using his fingers to count the points he is making to a group of youngsters. Ptolemy, Epicurus, Euclid and so many more are shown in intellectual activity. (Raphael gives special tribute to Michelangelo, the figure in the foreground with his left elbow on a marble block. In the summer of 1511, Raphael went into the Sistine Chapel when Michelangelo was painting its ceiling and, like everyone else, was overwhelmed by what he saw.) And in the lower left corner is a man wearing a turban crouching over the shoulder of Pythagoras who is demonstrating his mathematical thoughts on a slate.

Close-up of part of the School of Athens fresco.

The man in the turban is Ibn Rushd, known in the west as Averroes, the 12th century polymath born in Cordoba, Spain. Averroes was a doctor whose medical encyclopedia was the primer on human health for hundreds of years. He was also a jurist who served as the religious judge of Seville (1169-1172) and then chief judge of Cordova (1172-1182). He wrote several juridical treatises, but only one, Primer on the Discretionary Scholar, has survived. The title reveals much about his freedom of thought. While Averroes discussed the judicial decisions rendered by the courts operated by the then four schools of Islamic jurisprudence, and did so in the context of being bound by the specific words of the Prophet, he nonetheless brought practicality and the logic of rational deduction to his analysis and solution of legal issues. His scope was fully modern, dealing with contracts, property, marriage and divorce, and criminal law.

But, why did Raphael put Averroes in the Pope’s painting? The answer is Averroes was also a philosopher (known as The Commentator) whose commentaries on Aristotle translated into Hebrew and Latin in the 13th century first exposed western Europe to Aristotle who had been almost completely forgotten after the collapse of the Roman Empire 700 years earlier.

The connection between Averroes’s commentaries on Aristotle and Raphael’s depiction of Aristotle goes, however, much deeper.

Between roughly 750 and 1100, the center of knowledge and learning in the west was Baghdad. By comparison, London, Paris and Rome were hick towns. Brilliant Muslim scientists and artists made historic advances in almost everything: architecture, astronomy, chemistry, mathematics, medicine, music, poetry, philosophy and physics.

To explain what happened to this new knowledge, we need to go back to the year 661, 29 years after the Prophet’s death in 632. In that year, the Umayyad clan, centered in Damascus, dominated Islam and with unprecedented speed the Arabs conquered all of North Africa. In 711, an Arab-led army crossed the Straits of Gibraltar and within half a dozen years, much of the Iberian Peninsula was under Muslim rule.

In 750, the Umayyads were overthrown by the Abbasid clan who established their Caliphate in Baghdad. But the 19-year-old grandson, Abd-al-Rahman, of the deposed Umayyad caliph escaped the coup and in a journey worthy of a real life Ulysses, he reached Cordoba where he became emir of al-Andalus.

It was Rahman who started construction of the Great Mosque in Cordoba. It was his Umayyad successors who built libraries larger than the largest libraries in Europe, and who built the university in Cordoba, 100 years earlier than the first European university in Bologna, Italy. The cultural competition between these antagonists, Umayyads in Spain and Abbasids in Baghdad, was intellectually dazzling, producing unprecedented advances in knowledge.

In sum, Muslim intellectual accomplishments from the Middle East seeped west across North Africa and then north into Spain. Combined with those made in Spain, the new knowledge oozed across the Pyrenees and became an important foundation of the European Renaissance.

Averroes influenced both Moses Maimonides (1135-1204) and Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274), all three—Muslim, Jew and Catholic—declaring that faith and reason are compatible, and that it is ok to think!

David Lenefsky practices law in Manhattan. He gave an expanded talk on Raphael’s painting to the Young President’s Organization visiting the Vatican in 2007 and Amman, Jordan in 2010.