Why 2019 might finally bring a national privacy law for the US

The most surprising moment in a turbulent year for online privacy may have come in a House Judiciary Committee hearing in early December—when a Republican from Texas said the U.S. needed to follow the European Union’s lead.

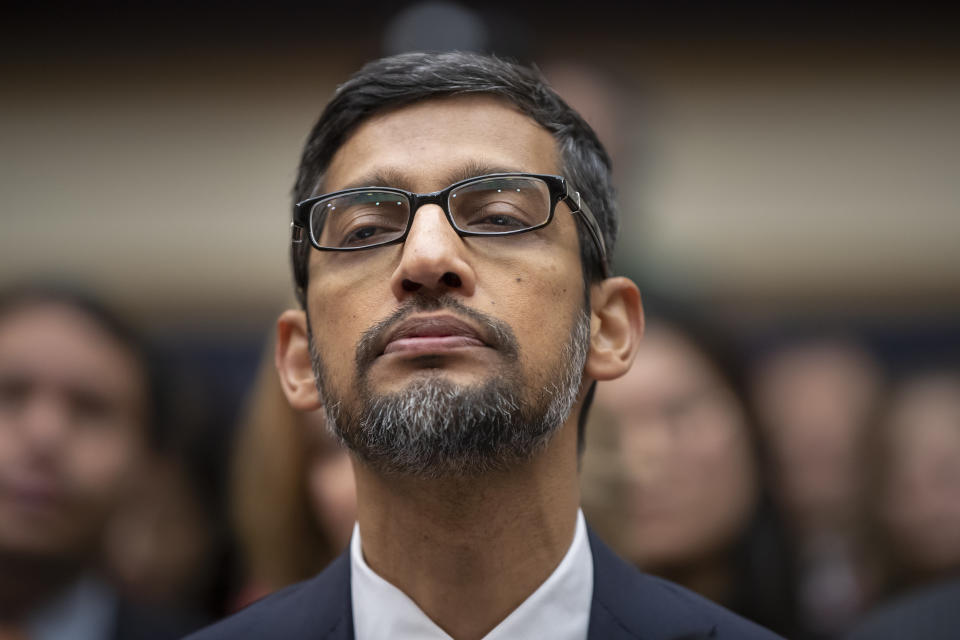

“We are playing second fiddle to the Europeans,” Rep. Ted Poe (R.-Tex.) told Google (GOOG, GOOGL) CEO Sundar Pichai. “They protect the privacy of their folks more than we do.”

If a GOP rep with a 90.2% lifetime rating from the American Conservative Union can join other longstanding Republicans in calling for federal privacy regulations and touting the EU’s sweeping General Data Protection Regulation as a model, the old sense of the possible has to look a little obsolete.

So, yes, we might finally get a national law that says companies can’t just show a privacy policy and tell you to click “Agree.” That could give you more chances to say no to the use and sharing of your data, require companies to disclose data breaches, and empower the government to fine and otherwise punish companies that break these new rules.

But that doesn’t mean that companies would have to ask for your permission before collecting your data, or that next year’s privacy offenders will pay a much harsher price than today’s.

Different proposals

We’ve reached this point in part because existing federal laws are so feeble. Outside of data involving financial details, health matters, or children, we essentially let companies state their intentions in privacy policies, after which the Federal Trade Commission can investigate violations of those commitments.

That approach’s frailty has been obvious for years, but two things have changed more recently. In May, the EU’s GDPR delivered such privacy rights as the ability to deny permission for marketing reuse of your data and then require a company to provide a copy of its data on you and then delete its own records.

Then in June, California passed the GDPR-esque California Consumer Privacy Act, which will enter into force Jan. 1, 2020—a date that puts a deadline on this debate.

“There will be a special impetus to enact comprehensive consumer privacy in some form,” emailed Dipayan Ghosh, a fellow at Harvard University’s Kennedy School of Government who earlier advised Facebook on privacy issues.

So meandering around in the usual mediocrity will result in a lot of privacy policy getting outsourced to Europe, California or both.

But what should a new national standard look like? Proposals from Rep. Suzan DelBene (D.-Wash.), Rep. Ro Khanna (D.-Calif.), Sen. Ed Markey (D.-Mass.), Sen. Amy Klobuchar (D.-Minn.), Sen. Brian Schatz (D.-Hi.), and Sen. Ron Wyden (D.-Ore.) disagree on things as basic as whether companies need your permission before using your data for marketing purposes.

These and other outlines also part company on secondary issues. Should a federal law preempt state regulations, the first plank of the U.S. Chamber of Commerce’s proposal? Should it ban discriminatory uses of data, a key suggestion from Khanna and a draft from the Center for Democracy & Technology? Should its penalties encompass Wyden’s possible jail time for top executives, a borrowing from the Sarbanes-Oxley accounting law?

If you like watching wonky policy debates, stock up on popcorn now.

“I don’t believe there has ever been a stronger need for baseline federal privacy law,” said Jason Kint, CEO of the online-publishing group Digital Content Next. “We have also reached the widest gap yet between consumer expectations and how the industry actually operates.”

From inaction to too-hasty action?

Hoping for that, however, requires looking past a long stretch of Congressional futility. The one time Congress has roused itself to action over the past two years was in early 2017, when Republicans voted to cancel pending Federal Communications Commission’s internet-privacy regulations.

Now could be different, but privacy advocates worry that the rush to pass something, anything to trump the California law will result in companies overpowering customers once again, leaving people with insufficient recourse when the next Equifax (EFX) breach happens.

Or a rush to legislate could lead to America importing too much of the GDPR. That’s an immensely prescriptive set of rules, including the dubious “right to be forgotten” that lets individuals compel search engines to hide some links from results to queries for their names.

“There's a strong public appetite for some sort of regulatory response, regardless of whether it is a good approach or not,” warned Cathy Gellis, a Bay Area lawyer who runs the Digital Age Defense project.

What could tip odds that Kint called “better than a coin flip” could be the next big privacy scare—but only if it’s bad enough.

And judging by how many people have dropped a social network or changed a search engine, we haven’t reached that point.

Wrote Amy Webb, a professor at New York University’s Stern School of Business and founder of the Future Today Institute: “We've seen a critical mass of people bemoaning the state of privacy online—but we haven't seen people actually changing their behaviors.”

More from Rob:

2 toxic story lines from Facebook won’t go away in 2019

Facebook wants to give you a way to fight having your posts taken down

Google Maps will now help you find Lime scooters

Microsoft is asking the government to regulate the company’s facial recognition technology

Email Rob at rob@robpegoraro.com; follow him on Twitter at @robpegoraro.