Why accounts of Philadelphia train passengers not intervening in a rape spread

The news was horrifying, a parable of inhumanity so grim that it was destined to go viral.

Two weeks ago, police said that passengers on Philadelphia’s elevated train watched a man rape a woman and did not intervene – and that some riders might have even recorded the 13 October attack with their cellphones. These onlookers did not call for help during the attack. The only person who dialed 911 was an off-duty transit worker, police alleged.

Related: Killed in seconds: why did the FBI shoot Jonathan Cortez in an Oakland corner store?

“I’m appalled by those who did nothing to help this woman,” Timothy Bernhardt, superintendent of the Upper Darby Township police department, said on 16 October. “Anybody that was on that train has to look in the mirror and ask why they didn’t intervene or why they didn’t do something.”

Bernhardt said the passengers who stood idly by might even face criminal charges, according to the Philadelphia Inquirer. Transit authorities made similar statements and the story rapidly spread around America and then the world as a grim symbol of an uncaring society, obsessed with social media over helping a victim being attacked.

But, it now seems, the story was not entirely accurate. In fact, the story is far more complex, revealing not only a brutal crime, but how a mistaken narrative ran wild in the press. At the same time, the appalling rape does reveal social problems in America, but they center around crime, the pandemic and policing, not the baleful influence of social media.

The Delaware county district attorney, whose office is prosecuting the case against alleged rapist Fiston Ngoy, said this portrayal of bystanders callously videoing the crime was “simply not true”. The prosecutor, Jack Stollsteimer, said it was wrong for authorities and media to advance the narrative that people were “callously sitting there filming and didn’t act”, calling this “misinformation”.

While Ngoy’s alleged interactions with the victim took place over a 40-minute period, starting with unwanted talking and then groping, the rape lasted about six minutes. Other riders were not on the train for the entire duration of their interaction, and might not have known what was happening, Stollsteimer said.

Surveillance video from the train revealed two passengers raised their phones toward the assault, and that one of those provided their video to authorities, AP said.

The dramatic turn of events has raised questions about how the original narrative took off, and why it might have staying power. There is no single answer – explanations are multifaceted and nuanced, ranging from police accountability to broad societal fears to longstanding concerns over public safety.

But one definitive starting point is the Kitty Genovese case. The 1964 murder of Genovese in New York City rose to international notoriety after a New York Times report claimed that nearly 40 people witnessed her being attacked and didn’t try to help her. The incident prompted extensive study, and the so-called “bystander effect” – a notion that when everyone thinks that someone else will act, nobody does – became de rigueur in psychology coursework.

Many years later, it emerged that the Times’ description of bystanders was incorrect. Far fewer people had actually witnessed Genovese’s murder than was reported and some did contact authorities. One of Genovese’s neighbors went out to help her, cradling the dying 28-year-old while waiting for paramedics. Most glaringly, an ambulance came to the scene “precisely because neighbors had called for help”, the New Yorker said in explaining how the original narrative was debunked.

Indeed, present-day research on bystanders stands in opposition to initial police accounts about the Septa passengers. A study based on closed-circuit television footage of 200 violent crimes across three countries found that “in 90% of those cases, bystanders did intervene”, explained Elizabeth Jeglic, a professor of psychology at John Jay College of Criminal Justice in New York City.

If the crime is clear, and it’s a serious crime, in almost all cases people will intervene

Elizabeth Jeglic, John Jay College of Criminal Justice

“So the bystander effect, as we had known it or had taught it for decades, may not be applicable today,” Jeglic said. “There are various factors that go into people acting and reacting, but for the most part, if the crime is clear, and it’s a serious crime, in almost all cases people will intervene.”

When bystanders are worried about their own safety, or physically incapable of intervening, they might step in by going for help or calling the police. Some have hypothesized that bystanders’ filming might even be an attempt at intervention. “They may be trying to help in videotaping it because it may be helpful in the prosecution of the crime later on,” Jeglic said.

Roy Peter Clark, senior scholar at the Poynter journalism institute in St Petersburg, Florida, said the concept of “master narrative” – effectively, cultural motifs that really stick – helps explain why the initial story resonated, even if facts ultimately don’t add up.

“That’s what makes it a master narrative – other stories are rejected as false or misleading or misinformation if they don’t fit the particular narrative,” said Clark, who has written about and discussed the Genovese case. Genovese’s story appeared to prove a story about “the loss of community, urban isolation and alienation”, not to mention the decline of good samaritanism.

The same thing may have been at play with the Septa attack.

“It may be magnified by the current moment – pandemic, catastrophic weather, economic disruption, people being unable to exercise the normal constructive communal rituals of a community and a society,” Clark said. “Whatever darkness there is in these master narratives, they may have been magnified by our collective current experience.”

Jeglic voiced similar sentiments, saying: “We are in a period of time where everything is very polarized and we often jump to conclusions without considering all aspects of situations.

“A lot of people want to be drawn to the narrative that there’s a lot of doom and gloom in humanity, that people are acting in very negative ways.”

But to dismiss the story would also be a mistake, say the people who actually live in the communities served by Septa and who ride its trains.

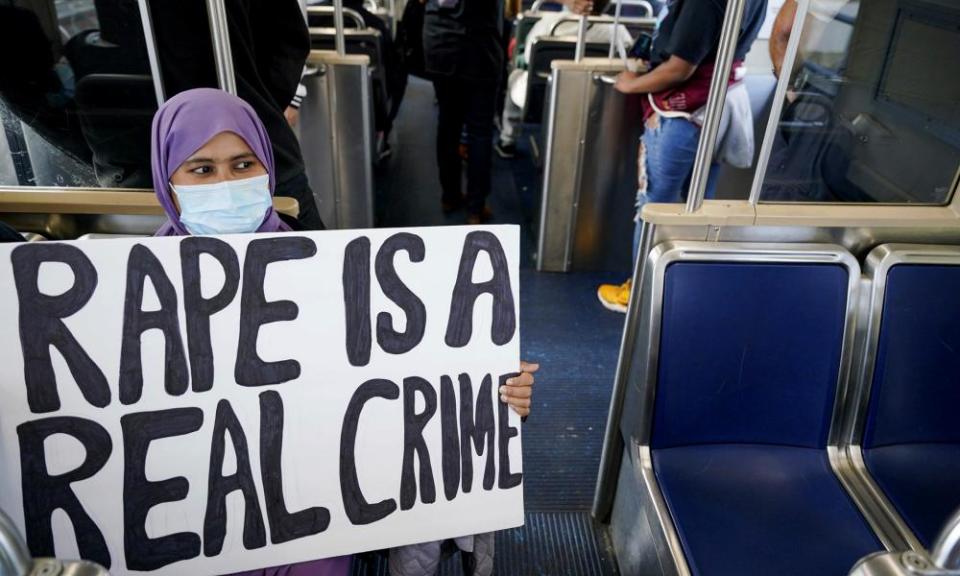

Septa passengers in Philadelphia and the suburb of Upper Darby didn’t find the notion of uncaring bystanders all that implausible, based on their own concerns about safety predating the rape. When presented with the fact that initial descriptions of uncaring bystanders appeared to be untrue, the consensus was that it made little difference.

“There’s no way you cannot see a sexual act,” said Victoria Evans, 38. “I would have rather taken my chances intervening than not saying anything.”

Evans, a certified nurse’s assistant, said that body language should have made people think twice about what they saw. “It would look uncomfortable. You can tell the difference. There’s no way nobody knew something was wrong.”

“I was really sad because I take the [train] everyday,” said Nasherah Tucker, 18. “I don’t really feel safe anywhere in Philadelphia, especially as a woman.” Tucker said the fact that the rape took place in public, on a train, was incredibly disheartening.

Even if the original police account regarding bystanders weren’t true, she said, “I think someone should have definitely said something.”

Many passengers, many of them people of color and especially women, do find riding public transport in the city a scary experience, where crime seems possible and a police presence seems thin on the ground.

“It was a mix of both being surprised and not being surprised,” said Noor Rana, a 19-year-old biology student, of her reaction to the incident. “I was kind of scared – scared for myself, for other women my age.

“Go tell the police. Get to another car. There’s so many things that you could do,” she said. “I don’t think there’s any excuse not to do anything.”

Would she feel differently about the bystanders if they didn’t know what was happening, as authorities have now said?

“This is Philadelphia. Crazy stuff happens, so I feel a lot of people tend to ignore stuff,” she said. Even if people mistakenly thought the encounter were consensual, they should have notified authorities, because “it’s still indecent”.

Some of those interviewed said that there needed to be a greater police presence on the the transport network. “They get paid to protect the public. You don’t see them do anything. Police don’t patrol inside trains,” said Esdras Taylor, 46. “The public is not going to do it. They should be doing their jobs.”

But in the aftermath of the attack, even before Stollsteimer provided more information, some residents remained optimistic.

I thought about it every day after I heard the initial report, but I just kept trying to picture it and I couldn’t

Jenice Armstrong, the Philadelphia Inquirer

Jenice Armstrong, a metro columnist with the Inquirer, did not believe the description of bystanders originally put forth by police. “It took me a while to write something,” Armstrong said in an interview. “I thought about it every day after I heard the initial report, but I just kept trying to picture it and I couldn’t.” She told herself that there had to be more to the story.

Before Stollsteimer provided the additional information, Armstrong was working on a column about how something didn’t seem to add up. Then came word of Stollmeister’s press conference. She rushed over there. “I was glad I did, because it bolstered my initial hunch I had – that it didn’t happen the way people were saying that it happened,” she said.

In the column Armstrong wrote after this information came out, she interviewed Septa police officer Tom Schiliro, who with his partner apprehended Ngoy when the train arrived at the 69th Street station. Schiliro told her that other riders quickly pointed out Ngoy.

“As soon as the train cars opened, everyone was pointing, ‘It’s over there! It’s over there,’” Schiliro told her. The week before, Schiliro arrested another man at this station for sexual assault. A good samaritan hurried to help the victim; Schiliro heard shouting and rushed to the incident.

“People are so quick to believe the worst about humanity. And ignore the good among us,” Armstrong wrote.

“Philly is a tough, tough city,” she said, “but I would like to think that it’s not so tough that you have passengers on a train standing around videotaping a woman being actively raped.”