Why artist Pilar Castillo made this hyper-real but very fake U.S. passport

Consider the Americana strewn across the United States passport: bald eagles, sheaves of wheat, Mt. Rushmore, the Statue of Liberty, the Liberty Bell, a clipper ship, cowboys, a locomotive and steamboat, purple mountain majesties — and on one of the later pages, a token totem pole.

Like a Hallmark musical greeting card, upon opening, one might expect “The Star-Spangled Banner” to play on a tinny loop.

In response to that document’s cheesy nostalgia — narrowing American identity to what seems a shallow civics lesson — Los Angeles artist and designer Pilar Castillo has created a hyper-real counterfeit passport, a fierce throwdown to what she terms a “staged” and “very colonized perspective.”

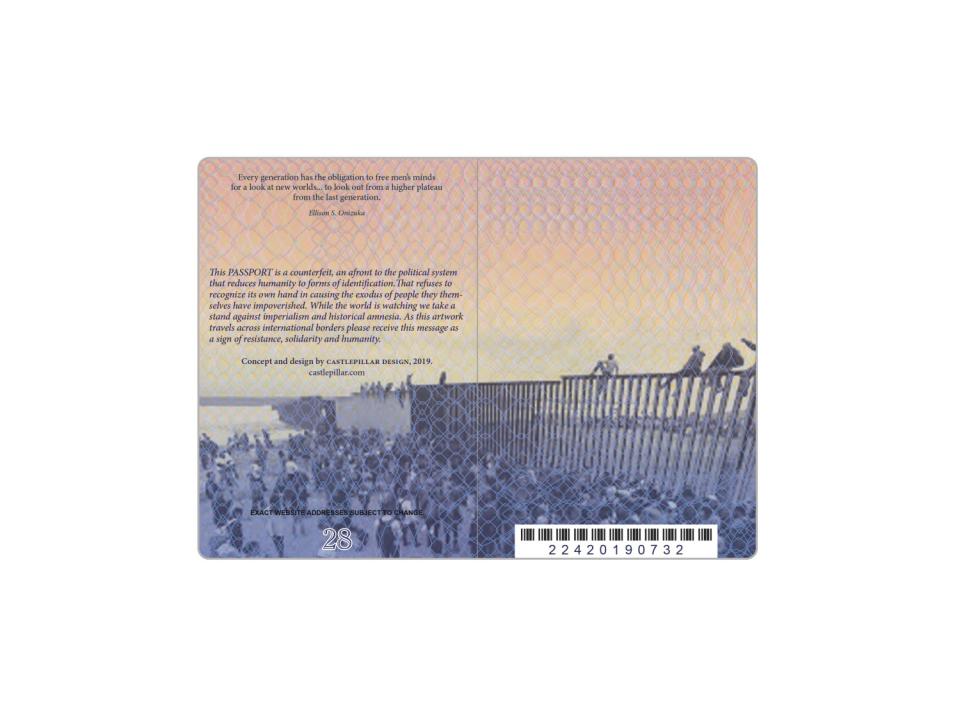

Belize-born Castillo created “Passport” in response to the 2018 Central American migrant caravan that was denied asylum, triggering a humanitarian crisis at the U.S.-Mexico border. The imagery in her work lays out a timeline documenting U.S. military incursions and exploitation of Central American labor and resources that precipitated the desperate journey.

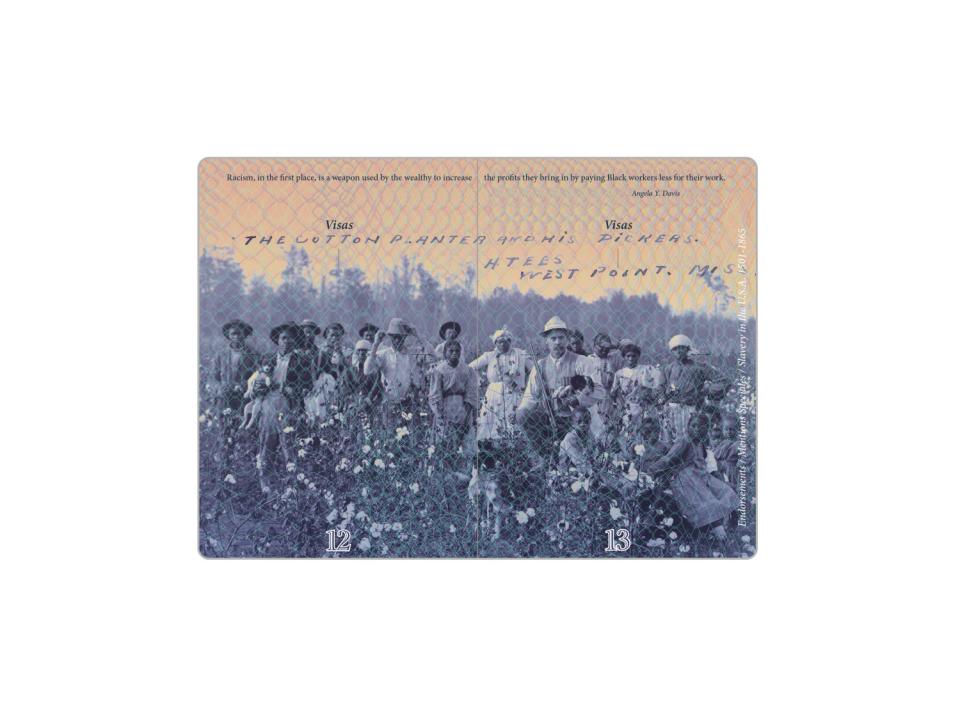

The subversive piece of protest art also lays bare, among other injustices, America’s still festering original sins: slavery and the slaughter of Native Americans.

“To talk about illegal immigration is to talk about a counterfeit experience, where you’re not accounted for, you’re denied basic human rights, you’re basically dispensable,” said Castillo, 43, who holds an MFA from Otis College of Art and Design.

Castillo, who operates CastlePillar Design from her studio in Ladera Heights, created “Passport" as part of an art-exchange among three women’s salons in Los Angeles, Paris and Mexico City. The work was also shown at SPARC gallery in Venice.

“This work is an homage to my mother,” said Castillo, who was a toddler when her mother left Belize at age 24 and “walked across the desert in hiding to reach the U.S.” Upon attaining legal status 10 years later, Ena Castillo sent for her daughter and other family members.

“She had no other choice; she wanted more for her family,” Castillo said. “She’s very strong-minded, determined — a very ambitious woman.”

“Passport” looks and feels like the real deal. A Border Patrol agent could plausibly crack open its cloned cover without any suspicion — remarkable given that it was printed at Office Depot using 10-point cardstock and copy paper. Castillo used a glue stick to adhere the 15 double-page spreads, vibrant with a lavender-fading-to-peach color palette.

As with an official passport, her work’s cover is emblazoned with the Great Seal of the United States. Look closely, however, and you’ll notice that the eagle’s head has been replaced with that of a rapacious vulture, its talon-clasped olive branch supplanted with a snake symbolizing the “sinister side” of Trump-era immigration policies, Castillo said.

The banner clasped in the bird’s beak is left blank. It usually bears the U.S. motto "E pluribus unum" (out of many, one). Castillo’s take: “It’s an empty promise at this point.”

Above the seal, the head of the Virgin of Guadalupe fills the usual circle of 13 stars, the child at her feet now caged behind vertical bars of the emblem’s shield.

“The shield that is supposed to protect is instead jailing the child,” said Castillo, referencing children separated from families and kept in chain-link enclosures when the migrant caravan arrived.

Inside, the work’s subtle illusion continues.

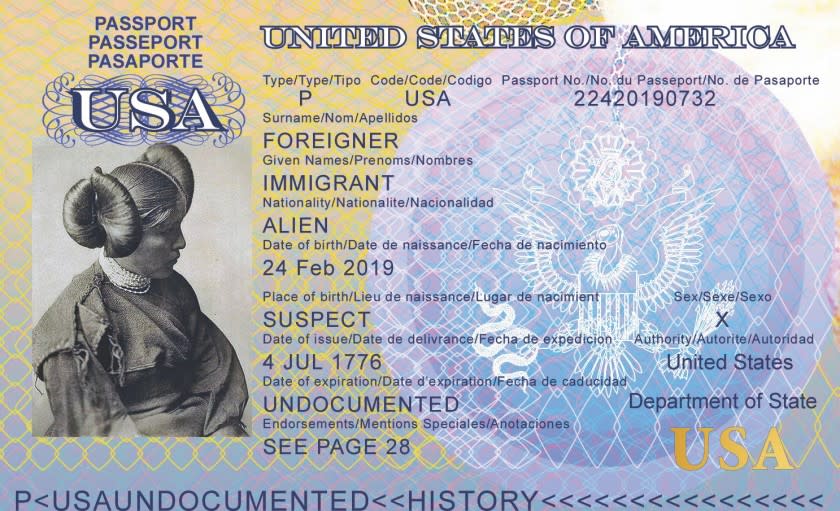

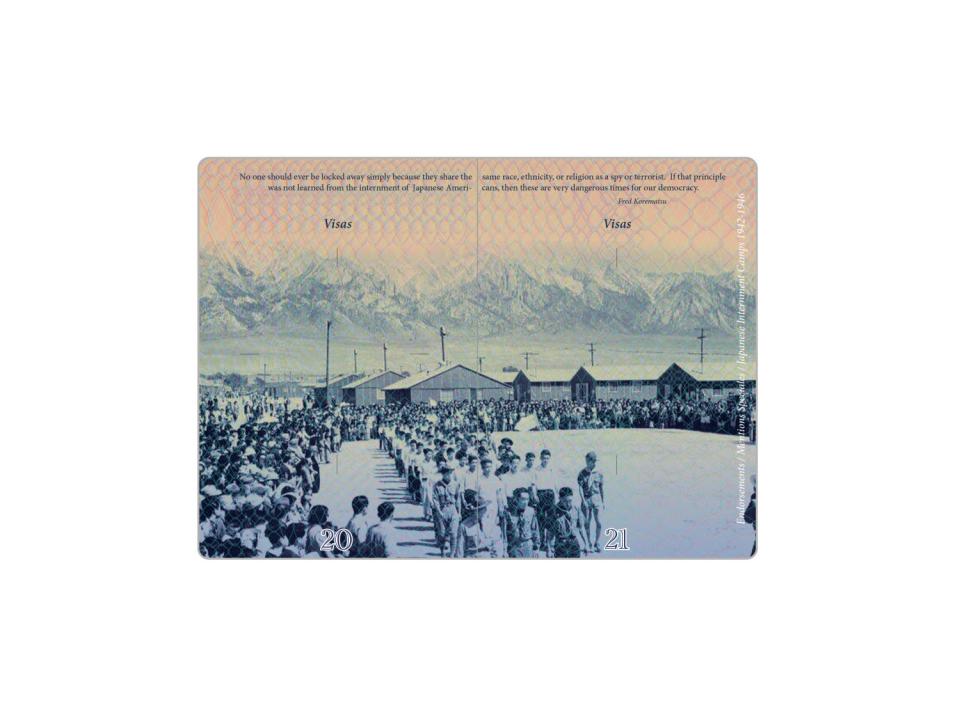

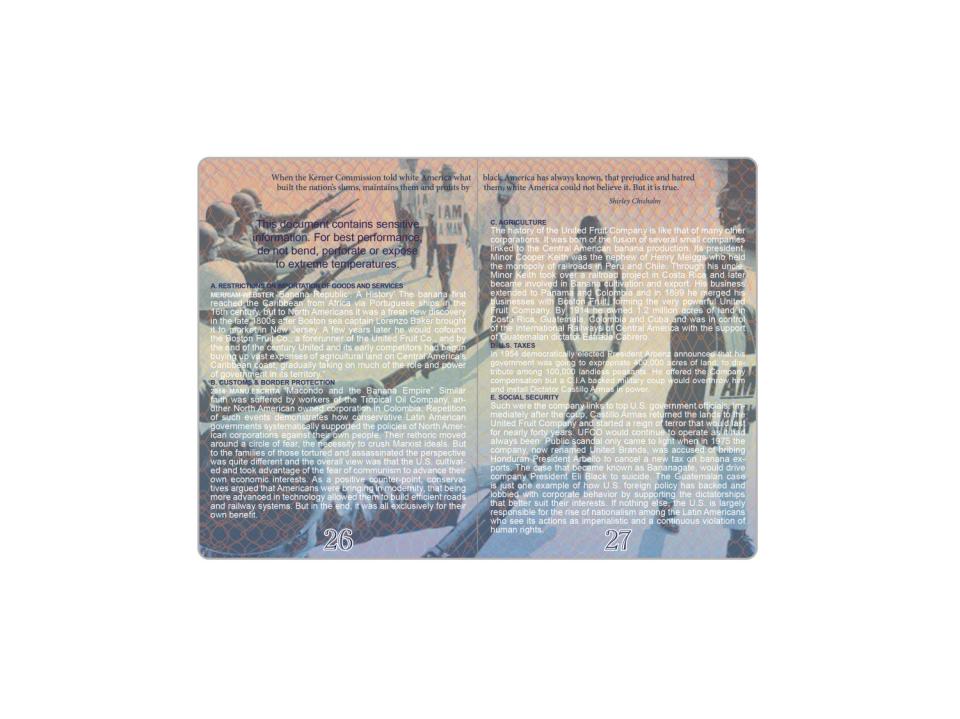

Execute a fast flip through the document and all still seems in order: The same wavy moire security print pattern overlays pages, except it’s actually a chain-link fence — a riff on the 30 security features in a U.S. passport as well as barriers to southern immigrants.

The mesh wire is especially haunting given that it’s superimposed over images depicting historical trauma, including hundreds of children posed before a Native American boarding school, an education movement that desecrated native culture.

On the identity page, a Hopi woman (photographed by ethnologist Edward S. Curtis) turns her torso and head away from the camera — a rejection of an “American” identity as well as the very document she carries. Her name is listed as “Immigrant Foreigner.” Her nationality: “Alien.” Place of birth: “Suspect.”

Castillo’s message: The native-born Hopi is erased along with the unwanted arrivals at U.S. borders.

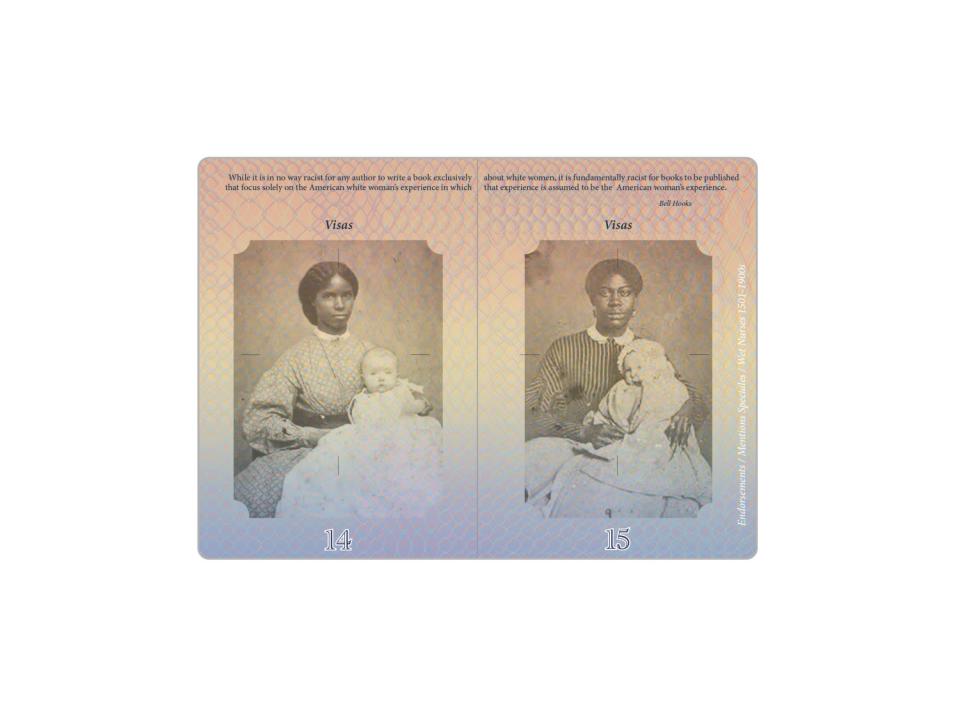

Other photos in Castillo’s ersatz work, paired with quotes (as in the official passport), include a Japanese American incarceration camp, migrant farmworkers, cotton pickers as well as enslaved African American wet nurses and nannies.

Castillo calls her approach “decolonizing design," a term of increasing popularity.

“‘Good design’ usually means European design — the story that’s being told is very narrow,” said Ramon Tejada, an assistant professor at Rhode Island School of Design. “There are missing stories.”

Castillo’s point about what an official passport is not telling is fascinating, he said.

That erasure lends the handmade document a kind of disturbing beauty, one that demands a reckoning.

“I am still a Central American woman,” Castillo said. “I feel solidarity with those who share this immigrant experience, along with future generations who seek the same opportunity. To make this kind of art in an era that is increasingly hostile toward immigrants, to confront these injustices — is empowering.”